Contents

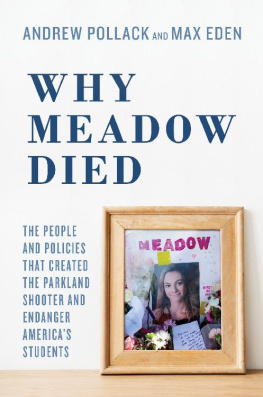

For the seventeen people murdered at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School:

Alyssa Alhadeff, Scott Beigel, Martin Duque, Nicholas Dworet, Aaron Feis, Jaime Guttenberg, Chris Hixon, Luke Hoyer, Cara Loughran, Gina Montalto, Joaquin Oliver, Alaina Petty, Meadow Pollack, Helena Ramsay, Alex Schachter, Carmen Schentrup, and Peter Wang

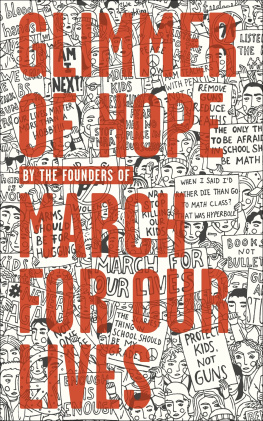

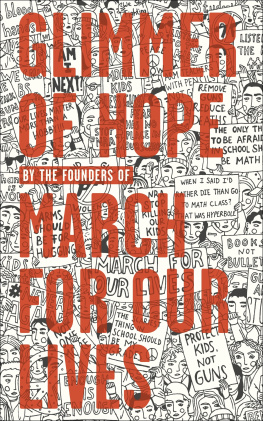

And for all of the March for Our Lives kids, and all you young activists inspired by them to get off your butts to make something change

1

Gun country. Half the country. Fighting them, provoking them, alarming them, was doomed to failure, more failure, decades of failurethey had to try something new. They had to engage them. So Jackie Corin had come to North Carolina six weeks after escaping her high school, but she was scared. It was just one guy. One guy was all it took. It was nerve-racking, because there was a guy staring me down and... He was an older white guy with gray hair under an NRA cap. An average-looking grandpa, she said. He just had a blank stare on his face the whole time, like I couldnt tell if he was there to hear us out or he was coming to make some chaos.

Jaclyn Corin, more comfortable as Jackie, is a petite blond teenager with fair skin, flowing hair, and a soprano voice that doesnt carry in crowds. But she has a presence. After she spoke, Jackie left the podium but remained seated onstage, out in the open. Just like the kids at her high school who were no longer at her high school, because they had been in the open. The people that went to the bathroom in the freshman building, they were easy targets, she said. Jackie had just left the freshman hallway when that jerk started shooting. It was all about timing. I literally walked out the doors that he walked into; it was like a span of fifteen minutes... She didnt complete the thought, but couldnt stop picturing it.

Jackies new friend Sarah Chadwick spoke after her at the rally, and then local college kids energized by their visit took the stage. The scary guys eyes barely skimmed them, they just kept burrowing into her. I felt like he was going to pop out a gun the whole time, she said. Alert security? Say what to security? And there was hardly any security.

Just four days earlier, Jackie had spoken to hundreds of thousands filling Pennsylvania Avenue, plus huge banks of TV cameras, but the contrast only heightened her fear. Obviously, the march on Washington was very well protected, she said. There was so much security, I was like, OK, if something happens to me onstage, the whole worlds going to see it. But at this event, there werent really a lot of people there to react.

The march on Washington had been covered as the culmination of their movement, but the kids had engineered it as a launchpad. Where they were headed was still hazythey were making it up as they went along. But they had an instinct. Jackie had come to North Carolina as part of an intentional sharp right turn. She had arrived with two objectives: to rally the waves of young new supporters eager to join the movement, but also to engage Second Amendment warriors. Preaching to the converted was easy. The real slog, if they wanted to get serious, was to convince hunters, collectors, and enthusiasts that no one was coming for their guns. They would not convince them today, or this year. But eventually. It didnt feel safe, though, and Jackie couldnt wait to get out.

Jackies fear has since faded, but it lurks and swells unpredictably, in waves of silent terror that can knock her back at any moment. Fear was a constant stealth companion in the first strike she engineered in Tallahassee, the five-week sprint to the March for Our Lives (MFOL) in Washington, DC, and the grueling Road to Change bus tour, consolidating their network all summer along ten thousand miles of American highway. Fear was with her all the way to the midterms, which were their primary objective from that first weekend, when they concluded they would never break the logjam on gun legislation without changing some legislators. And putting the rest on notice.

Its a particular sort of fear Jackie shares with survivors of Columbine and the Pulse nightclub shooting. Most mass shootings end within fifteen minutes, but Jackie and her friend Cameron Kasky were crouched in lockdown on the day of the shooting for three and a half hours. Throughout it, they got updates on the carnage by text and Twitter, as seventeen students and staff were murdered around themlong enough to ride the waves of panic, fear, and helplessness to settle on simmering rage. By the time Jackie and Cameron hit their beds that night, this movement was in motion.

It was speed that launched this movement, and a breadth of talent that packed its punch. That first night, Cameron, Jackie, and David Hogg started simultaneously on separate tracks to completely different movements, which they fused forty-eight hours later to form a juggernaut. Camerons first and best move was assembling talent. By Saturday, when Emma Gonzlez went viral, two dozen creatives were conjuring up a new movement in Cams living room.

I spent ten months shadowing these kids, and they were relentless, frequently racing around the country in opposite directions. That was their secret weapon: waging this battle on so many fronts with a host of different voices, perspectives, and talentshealing each other as they fought.

2

I swore I would never go back. I spent ten years researching and writing Columbine, and discovered that post-traumatic stress disorder can strike even those who have not witnessed a trauma directly. First responders, therapists, victim advocates, and journalists are among the vulnerable professions, but I had never heard of secondary traumatic stress, or vicarious traumatization (VT), until it took me down, twice, seven years apart. I learned that it comes in many forms, that PTSD is very specific, and less common than depression, which struck me. I was sobbing all day, mostly in bed, then slumped in a chair, unable to work effectively, or to do much of anything. Thats when I agreed to some of my shrinks terms: read no victim stories the first week after a tragedy; watch no TV tributes or interviews with survivors unless I promised to hit the mute button if I started to feel the warning signs. I could study the killers at will, because they didnt burrow inside meit was the survivor grief that did me in.

Even years after Columbine, I had no idea it had drawn me in for life. Since that day, I have tracked every major tragedy in some capacity as a journalistbut always at a distance of either time or space. In the immediate aftermath, I engage with a cadre of mental health and criminology experts, and with countless informal survivor networks, especially the many Columbine survivors I now count as friends. Months, or preferably years, later, I have gone back to the scene of some of the worst crimes. I work with John Jay Colleges Academy of Critical Incident Analysis (ACIA), which brings a small team of experts and survivors together for a three-day study of one critical event each year. I studied the Virginia Tech and Las Vegas tragedies on-site, and Norways 2011 Workers Youth League attack from New York City. But I could never plunge back into the scene of the crime while the wounds were still raw. Nor could I bear the prospect of documenting horror another time.

Parkland changed everythingfor the survivors, for the nation, and definitely for me. I flew down the first weekend, but not to depict the carnage or the grief. What drew me was the group of extraordinary kids. I wanted to cover their response. There are strains of sadness woven into this story, but this is not an account of grief. These kids chose a story of hope.

The Parkland uprising seemed to erupt out of nowhere, but it had been two decades in the making. The school-shooter era began at 11:17 a.m. MDT, on April 20, 1999, at Columbine High School, in Jefferson County, Colorado. There is a photograph that became iconic, which I described in