For the rich past and boundless future of fashion.

For my family, new and old.

For Paris.

CONTENTS

Guide

On September 26, 2012, as the spring/summer 2013 ready-to-wear collections kicked off in the City of Light, Womens Wear Daily dropped a notable cover story illustrated with a large snapshot of Hedi Slimane, the newly appointed creative director at Saint Laurent, set against one of Raf Simons, the newly appointed womenswear designer at Christian Dior. The headline, appropriately, read Paris Face-Off.

These coincidental engagements marked the latest in fashions now longstanding tradition of assigning young talent to reinvigorate its stalwart ateliers. The journalist Joan Juliet Buck astutely dubbed this strategy the Lazarus movement, a reference to the biblical Lazarus raised from the dead in the Gospel of John. The iconography of these Lazarus brandsSaint Laurent, Christian Dior, Chanel, Lanvin, Givenchy, Herms, Louis Vuitton, and Balenciaga, to name simply those detailed in this bookis what sustains them, and it has been calcified by the talents and signatures of their respective founders and then the contemporary directors now assigned to their legacies, if not by any number of interim designers over the last sixty years. The remains are a fossilization of fashion in which one eager enough to peel away layers of interpretation, definition, and, of course, branding is afforded a view of the unique and compelling trajectories that together have influenced womens dress for more than one hundred years.

Though both Herms and Louis Vuitton began as luxury leather goods purveyors in the nineteenth century and developed their apparel arms as extensions of preestablished customer caches in the twentieth century, the majority of the storied Paris houses were launched as haute couture establishments, dedicated to custom-made fashion concoctions that demanded labored handwork and precision of cut. Perhaps most crucial to the success of any given couture atelier at the timeand still so todaywas the creation and exploitation of a characteristic style or look intrinsic to the house identity and recognizable by the consumer. In her critical view of postmodern design, Fashion Zeitgeist (2004), theorist Barbara Vinken explained, In haute couture, the griffe [signature] is the guarantee of a limited edition, and signifies the hands-on involvement of the master-designer. Through it, the fashion-creation approaches the artwork; it becomes a collectors object. The griffe substantiates genuine value as a branded Louis Vuitton monogram fabric, the orange ribbon of Herms, or the C and D accessory charms of Christian Dior, but is also manifest in corporeal details and silhouettes(Chanels tweed suit), colors (Lanvin blue), or fabrics (Balenciagas precious gazar) that have become established marks of a given couture house over time.

Though every lifestyle brand has its signatures, the Parisian ateliers that currently guide French fashion are particularly adept at mining, updating, and promoting old-world couture traditionsfamiliar details, crests, shapes, or patternsthat serve to legitimize their designs while ultimately reinforcing a unique language that has proven both stylistically and commercially viable. By nature deferent to the dictates of quality that their founders established, these companies have the challenging task of translating the vocabularies of couture-level luxury to a fast-paced global market reliant on ready-to-wear and the commercial licensing of accessory goods. Some among them (Chanel, Givenchy, and Dior) resolve this chasm by maintaining haute couture collections and presentations. Others (Balenciaga, Louis Vuitton) apply couture-level technique (as with a Vuitton mosaic clutch made of more than one thousand fragments of actual eggshell) and technology (Nicolas Ghesquires scuba silks or gold chain mail) to elevate their collections to high art. The result in either case is a stronger lineage from and connection to the artisanal traditions and innovations of the original ateliers.

Perhaps it feels uncomfortable to those of us who fetishize a finely ruched trim or an elaborate framework of appliqueven a well-sculpted shoulderto admit it, but the often-asked question Will haute couture survive? must necessarily be followed by For whom does it currently exist? The latter query is not resolved by pointing to the gaggle of aristocratic Russian socialites, Dubai royals, European jet-setters, and American nouveau riche who purchase couture todayfor the couture client is inarguably but a ghost of who she once wasbut rather in addressing coutures contemporary function. Is couture simply a notion around which the Parisian crateur pivots in order to inspire and innovate, justifying his own painstaking artistry?

In the July 2006 issue of American Vogue, fashion journalist Mark Holgate labeled the collections of the prominent French purveyors as the demi-couture, which can be found somewhere between industrially produced designer fashion (the prt--porter...) and clothes created entirely by hand and after three fittings with a client (the haute couture). Holgates observation is underscored by the designers explicit interest in maintaining couture standards, even in the face of a highly commercial creative cycle. The American designer Marc Jacobs, who launched Louis Vuitton into womens ready-to-wear in 1997 and built a multimillion-dollar collection in the fifteen years to follow, has said, The French rules for couture are like the rules for language... I actually quite admire this... If you have respect for something or believe its a thing of beauty, it should be preserved and it should last. Lanvins former designer Alber Elbaz has spoken out about how the relentless pace of the ready-to-wear industry has stifled creativity, while former Herms designer Christophe Lemaire has been a vocal devotee of slow fashion, or the mining of a calculated aesthetic over several seasons (rather than a barrage of trend redirections framed by showstopping theatrics). But where Jacobs pontificates on coutures boundaries and Elbaz and Lemaire seek to separate artistry from industry, American journalist Cathy Horyn has distilled simply that couture is a concept that offers the luxury of concentrating on a single idea.

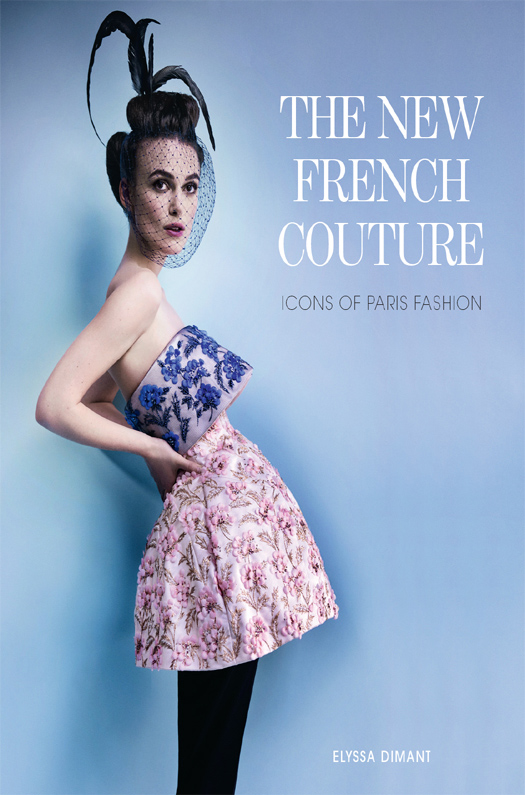

For the ateliers featured in this book, the single idea is that of brand identity, forged from both reverence (couture) and revolution (ready-to-wear), but grounded in heritage. The New French Couture examines the established signatures of eight distinct establishments, the elements of French art and culture that inspired them, and their resonance in contemporary French fashion.

Part I, Identities, reveals the prescience of the belle de jour (as the brainchild of Saint Laurent), the drama and impact of la romantique (as envisioned by Christian Dior), the modern-mindedness of la garonne (an androgyne modeled after Chanel), and the distinction of la vraie femme (the essence of femininity, as clarified by Lanvin) in an attempt to map the many faces of the French muse. These fashion personalities are in each case extensions of the houses respective founders, and have provided stable ideals upon which various cuts, shapes, textiles, and decorations can be applied to diversify the brand aesthetic from season to season and even over decades. Part II, Places, locates points of historical origin from which French style continually evolves, even metamorphoses, specifically the French salon (Givenchy), the realm of sport (Herms), luxury travel (Louis Vuitton), and the future (Balenciaga) to which Paris aspires as the epicenter of global fashion.