Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

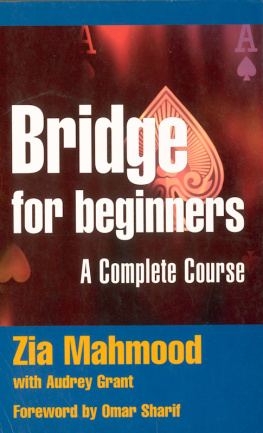

Cinematic Overtures

Leonard Hastings Schoff Memorial Lectures

Cinematic Overtures

HOW TO READ OPENING SCENES

Annette Insdorf

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2017 Annette Insdorf

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54406-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Insdorf, Annette, author.

Title: Cinematic overtures : how to read opening scenes / Annette Insdorf.

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2017] | Series: Leonard Hastings Schoff memorial lectures | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017009183 | ISBN 9780231182249 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780231182256 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Motion pictures.

Classification: LCC PN1994 .I4645 2017 | DDC 791.43dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017009183

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover image: Film still from The Piano . Image provided by the author with permission from Jane Campion, the films writer and director.

Cover design: Lisa Hamm

Dedicated to the memory of Guy Gallo

Contents

F irst impressions count. A strong opening sequence leads the spectator to trust the filmmakers. My experience watching filmsas well as teaching cinema history and criticismsuggests that a great movie tends to provide in the first few minutes the keys by which to unlock the rest of the film. Gifted directors know how to layer the first shots in a way that prepares for their thematic concerns and stylistic approach. Sometimes the opening sequence is intentionally misleading, inviting the viewer into active participation with the film, alert to the images and sounds that will be developed throughout subsequent scenes.

This book initially took shape as a series of lectures I was invited to deliver at Columbia University. In November 2014 I offered three Leonard Hastings Schoff Memorial LecturesOpening as Prologue, Opening as Misdirection, and Opening as Actionincluding numerous film clips. Reshaping the lectures into a book meant finding a new and more coherent structure, which led to these eight distinct approaches to opening a motion picture. Because adaptation places cinematic storytelling in relief, I also highlight three case studies of a striking opening translated from a novel.

If Cinematic Overtures had been conceived as strictly a book of film analysis for other scholars or students, I would not be using the first person singular. But since I hope the book will reach a diverse group of readers interested in thinking and talking about film, the Iand all the idiosyncratic connections it impliesremains. Each section is designed as a first steprather than end pointto engender the readers heightened viewing of films and reflection upon them. The tone is purposefully accessible, intended to reach a wide audience of cinephiles both within and outside academia. As the title proposes, the reader is invited to enter into the unfolding of meaning through close analysis of opening sequences. To provide a visual reference for this written text, I have included frame enlargements. (The electronic version of the book has an accompanying compendium of carefully selected clips.)

High-profile titles and undiscovered gems rub shoulders throughout Cinematic Overtures . This mix of mainstream and high-art films reflects my own overlapping areas of scholarship and journalism. I have included lesser-known motion picturesoften with more detailed analysis than the famous onesin the hope that readers will seek them out. While it might be unusual for an author to cite her students papers, teaching at Columbia nurtures a book of this kind: the essays of both MFA and undergraduate students often reveal how sophisticated films engage viewers and generate insights. I believe that all of the titles discussed here are linked by the alertness and engagement they ask of viewers from the very beginning. Although we often watch movies without looking attentively or hear without listening closely, through openings like those described in Cinematic Overtures , filmmakers trust the audience to actively make connections.

I appreciate the wise counsel of Philip Leventhal, my editor at Columbia University Press, and the ongoing support of my agent, Georges Borchardt. For the invitation to deliver the Schoff Lectures at Columbia, I am grateful to Robert Pollack. Robert Brink, my digital editor, provided valuable assistance with frame enlargements and clip selection. Finally, I thank Mark Ethan Toporek for viewing films with me, suggesting areas of exploration, reading drafts with a constructively critical eye, and being the most loving ally.

Saul Bass , Talk to Her, Knife in the Water, Camouflage

M y point of departure is close analysis of the opening sequences of motion pictures. When discussing films, I share with other viewers how superior movies provide within the first few minutes the thematic and stylistic components that will be developed throughout the film. This is of course similar to how great novels offer in the initial two paragraphs the keys by which to unlock the rest of the book. In addition to establishing the tonewhether tense, ironic, romantic, frightening, comic, nostalgic, or self-consciousthe opening introduces meaningful motifs; these can include windows, circular images, or elemental imagery such as water and earth. The opening makes us aware of the point of view: who is telling the story. Once upon a time, once upon a time were the four words that introduced a tale. The voice of the omniscient third-person narrator framed the story with a soothing movement into a past. Film is also once upon a space or, more appropriately, once into a space as the camera explores the space of the frame. Psycho and Sunset Boulevard provide fine examples, moving voyeuristically from an exterior objective shot into a window, penetrating a rooms intimacy.

Why focus on the instigating moments of a motion picture? Victor Hugo called opening signals inexorable revealers.

My chapter divisionsmuch like my Schoff Lecture titlesare not rigid but fluid and overlapping. An opening can be both a prelude and a misleading introduction (for example, when the voice-over narration is spoken by a character who turns out be dead). And an opening can be part of the action while providing the equivalent of a frame around a painting. Philip Kaufmans Quills (2000) is a vibrant illustration, opening with the image of a beautiful young woman as the male voice-over says, Dear Reader, Ive a naughty tale to tell, plucked from the pages of history. Tarted up, true, but guaranteed to stimulate the senses. While these lines (from Doug Wrights adaptation of his own play) prepare us for an erotic encounter, the camera gradually reveals an executioner at the guillotine. The public brutality counterpoints the purple prose of the Marquis de Sade: the woman is about to lose her head literally rather than figuratively. Kaufman invites the viewer into active participation with the film, foreshadowing both the sensuality and self-consciousness of subsequent scenes. And the opening of The Queen (2006) acknowledges that the function of a frame is to hold the picture and keep it in place. In a long take, Queen Elizabeth (played by Helen Mirren) poses for an official paintingan appropriate introduction to a character whose public image is imperious and immovablebefore turning to the camera. As in his earlier film Dangerous Liaisons (1988), director Stephen Frears excels in female portraiture.