Bibliographical Note

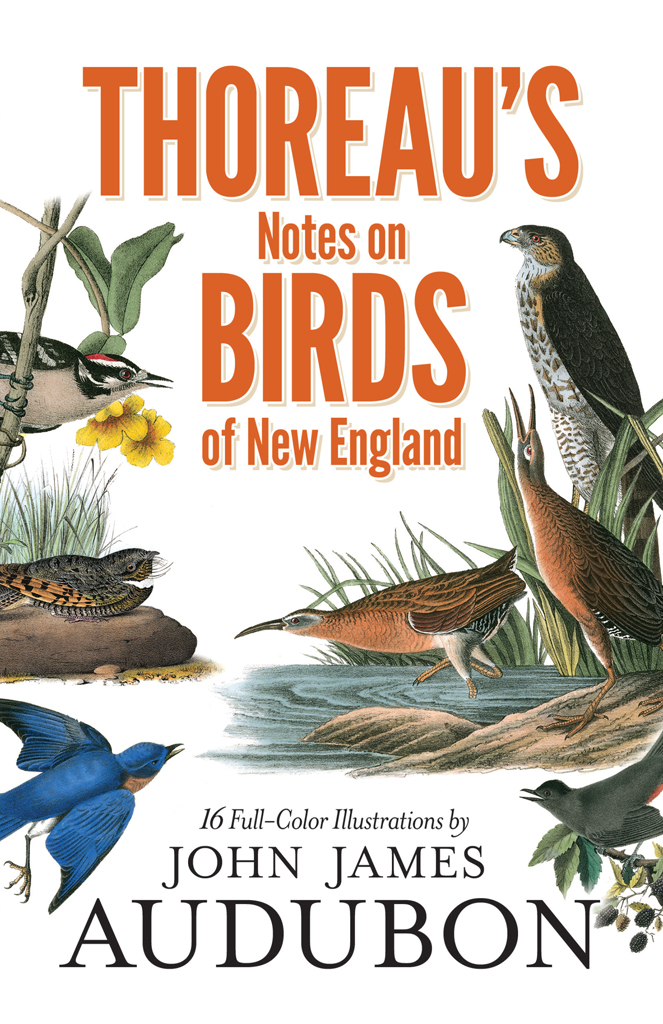

This Dover edition, first published in 2019, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published in 1910 by Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York, under the title Notes on New England Birds. This edition does not contain the original photographs included in the 1910 edition; however, it does include 16 full-color plates by John James Audubon. The original edition had a fold-out map, which has been omitted here. To view the content of this map, please see: http://www.doverpublications.com/0486833844/.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Thoreau, Henry David, 18171862, author. | Allen, Francis H. (Francis Henry), 18661947, editor.

Title: Thoreaus notes on birds of New England / Henry David Thoreau ; edited and arranged by Francis H. Allen ; with illustrations by John James Audubon.

Other titles: Notes on the New England birds

Description: Dover edition. | Mineola, New York : Dover Publications, Inc., 2019. | This Dover edition, first published in 2019, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published in 1910 by Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston and New York, under the title Notes on New England Birds. This edition does not contain the original photographs included in the 1910 edition; however, it does include 16 full-color plates by John James Audubon.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018046106 | ISBN 9780486833842 | ISBN 0486833844

Subjects: LCSH: BirdsNew England.

Classification: LCC QL683.N67 T53 2019 | DDC 598.0974dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018046106

Manufactured in the United States by LSC Communications

83384401 2019

www.doverpublications.com

Contents

List of Plates

[The sixteen color plates appear between pages .]

PREFACE

SCATTERED through the fourteen volumes of Thoreaus published Journal are many interesting notes on the natural history of New England, and a large proportion of these relate to birds. In the belief that readers and students would be glad to have these bird notes arranged systematically in a single volume, this book has been prepared. It will perhaps be a matter of surprise to many readers to learn how much Thoreau wrote upon this one branch of natural history, and how many species of birds he found something to say about that was worth the saying. Thoreau was seldom dull, even in mere records of commonplace facts, and the reader of this book, though he may be well acquainted with the authors picturesque style, can hardly fail to be impressed anew with his power to convey a vivid and interesting picture in a few words.

It was, indeed, as a describer rather than as an observer that Thoreau excelled. He never acquired much skill in the diagnosis of birds seen in the field. He never became in any respect an expert ornithologist, and some of the reasons are not far to seek. He was too intent on becoming an expert analogist, for one thing. It better suited his genius to trace some analogy between the soaring hawk and his own thoughts than to make a scientific study of the bird. Moreover his field, including as it did all nature, was too wide to admit of specialization in a single branch. Then, too, he lacked many of the helps that to-day smooth the way for the beginner in bird-study. He had no intimate acquaintance with ornithologists or scientific men of any sort, and after giving up the gun in his young manhood he waited many years before he purchased a glass, and then bought a spy-glass, or small telescope, an implement which was useful in identifying ducks floating far off on the waters of the river or Walden Pond, but could hardly have served him very well with the flitting warblers of the tree-tops. The books, too, in those days were far from adequate. Wilson and Nuttall, upon whom he chiefly relied, are unsurpassed in some respects by anything we have to-day, but their descriptions of birds were not designed to assist in field identification, and they were by no means infallible in other matters. These books were not new even in Thoreaus day, but they were the best ornithological manuals to be had, and with Wilson making no mention of so common a bird as the least flycatcher, and Nuttall in ignorance of the existence of the olive-backed thrush, we may pardon Thoreau a few misapprehensions.

As a matter of fact, Thoreau seems to have seen things pretty accurately,when he saw them at all, for he was sometimes strangely blind to the presence of birds which must have been fairly common inhabitants of the woods and fields through which he roamed. His chief difficulty in identification was, perhaps, a tendency to jump at conclusions,as when, meeting with the pileated woodpecker in the Maine woods, he at once set it down as the red-headed woodpecker (Picus erythrocephalus), evidently because of its conspicuous red crest. The reader who desires to make a special study of Thoreau as an ornithologistto learn his mistakes as well as his discoveriesmust go to the Journal itself. There he will find the true and complete record of Thoreaus bird observations,including all the brief notes which are of no value except in the compilation of migration data and the like, and the mere identifications, mistaken and otherwise. In the present volume it has seemed best to confine ourselves to the notes which have some intrinsic value, whether literary or scientific,using both terms in a liberal sense.

It is to be borne in mind that these notes are from Thoreaus Journal and therefore have not always been cast in a final literary form. Regarded as literature, many of them stand in need of shaping and polishing, but they are none the less interesting for that, and it is also to be remembered that Thoreaus notes were seldom mere records of fact. He never forgot that writing was his vocation, and when he wrote it was for the purpose of recording his thoughts in the best language that came to his mind at the moment. He wrote rapidly, and occasionally a word was omitted or the wrong word slipped in, though that happened with rather surprising infrequency, all things considered. The editor of this volume was associated with Mr. Bradford Torrey in the editing of Thoreaus complete Journal, and he can affirm from personal knowledge that Thoreaus omissions and slips of the pen are all carefully indicated there. In the present book it has seemed best to simplify things for the reader by omitting the brackets from interpolated words in the case of the unimportant ones where the word to be supplied was obvious, and to retain them only in the case of the more important words, or where there was any possibility of a misapprehension of Thoreaus meaning.

It may be well here to point out the office of the brackets, [ ], as differentiated from parentheses, (), since their use is not always understood by readers. Brackets, as used nowadays by most writers and printers, show the interpolations of the editor, while the parentheses are the authors own. Thus, in the present volume, a question-mark in brackets, [?], indicates that the editors of the Journal were in doubt as to whether they had rightly interpreted Thoreaus handwriting, but the same in parentheses, (?), is Thoreaus own query.

So, too, in the notes, those which are bracketed are the editors, while the unbracketed notes are later annotations by Thoreau, usually in pencil, upon the pages of his manuscript journals. The editor has felt free to quote or paraphrase the notes of the published