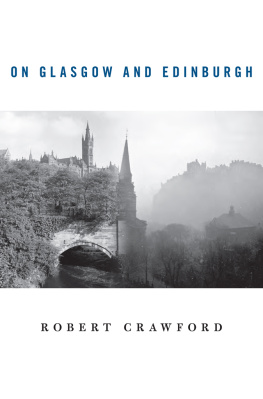

On Glasgow and Edinburgh

On Glasgow and Edinburgh

Robert Crawford

The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England  2013

2013

Copyright 2013 by Robert Crawford

All rights reserved

Jacket art: Glasgow University and misty castle, photos by Haywood Magee, Getty Images

Jacket design by Tim Jones

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Crawford, Robert, 1959

On Glasgow and Edinburgh / Robert Crawford.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-674-04888-1 (alk. paper)

1. Glasgow (Scotland)History. 2. Edinburgh (Scotland)History. I. Title.

DA890.G5C87 2013

941.34dc23 2012020952

Book design by Dean Bornstein

for both with love

Contents

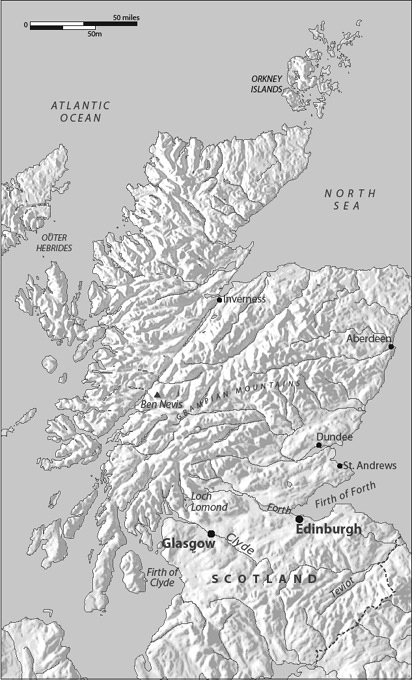

Like good and evil, Glasgow and Edinburgh are often mentioned in the same breath but regarded as utterly distinct. The rivalry between these cities, which is so long-standing that it has become proverbial, sets them alongside other urban centresLos Angeles and San Francisco, Moscow and St. Petersburg, Rio de Janeiro and So Paulowhich like to jockey for supremacy within their nations. Though the two are almost comically diminutive when compared with Madrid and Barcelona, let alone with Beijing and Shanghai, Glasgow (population 600,000) and Edinburgh (population 500,000) are much smaller than most other internationally celebrated pairs of urban rivals. They are also absurdly closer together: only forty miles separates the two lowland Scottish cities; to travel by train from the centre of one to the centre of the other can take as little as forty-five minutes. In spirit, though, each considers itself far removed from its counterpart. Perhaps the most intellectually honest way to go from the west-coast city to the east-coast city would be to fly westward from Glasgow Airport over the Atlantic, crossing North America, the northern Pacific, Asia, and continental Europe, before descending over the Firth of Forth on the eastern seaboard of Scotland and then landing at Edinburgh Airport. That way, at least, one would arrive from Glasgow psychologically prepared.

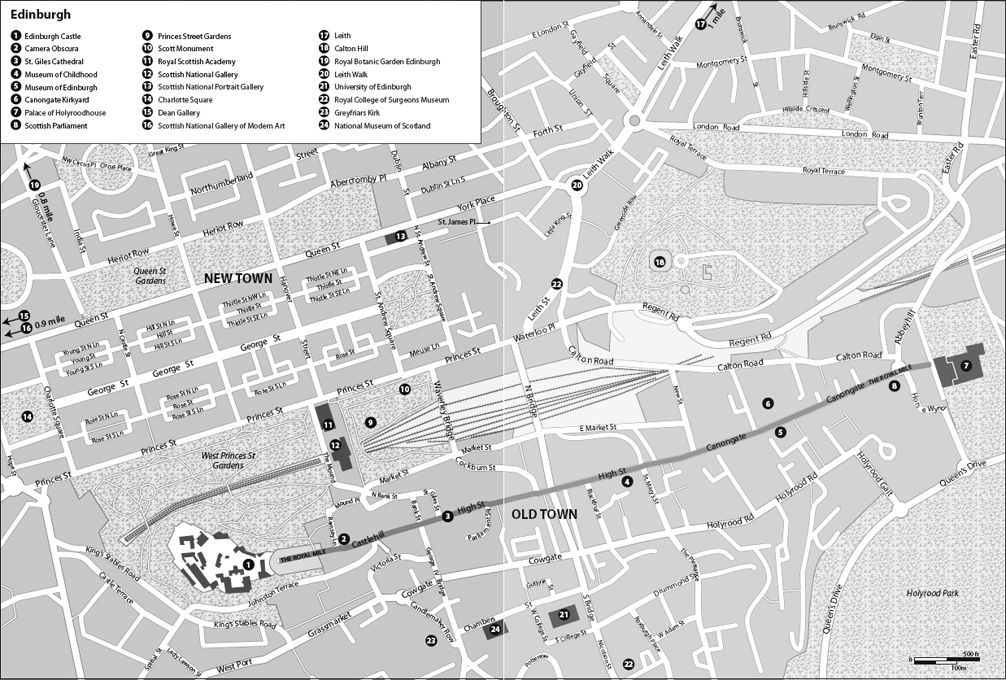

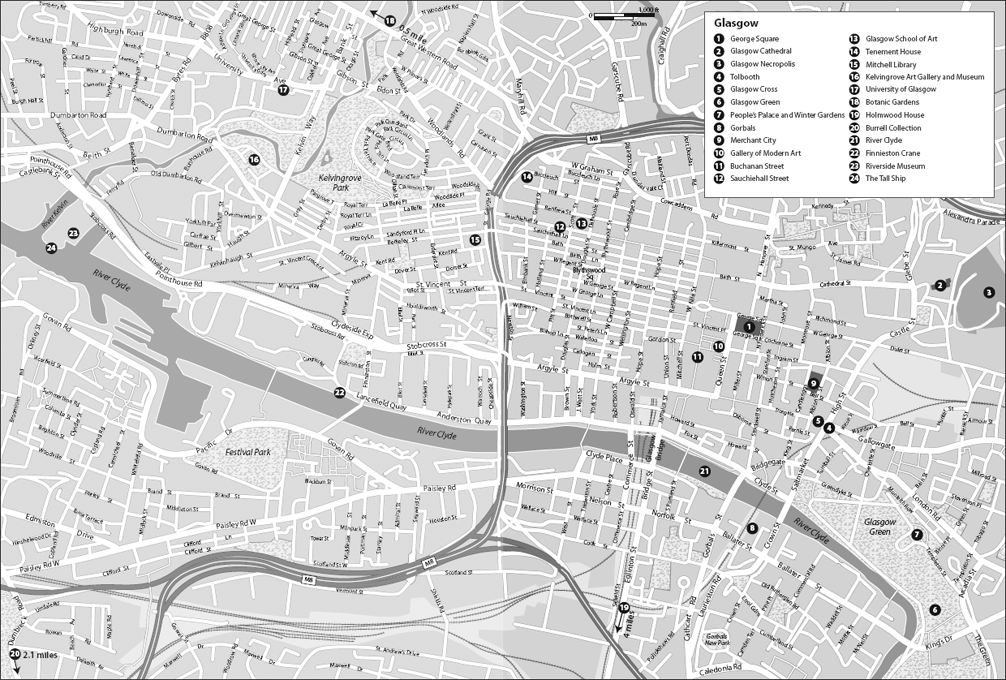

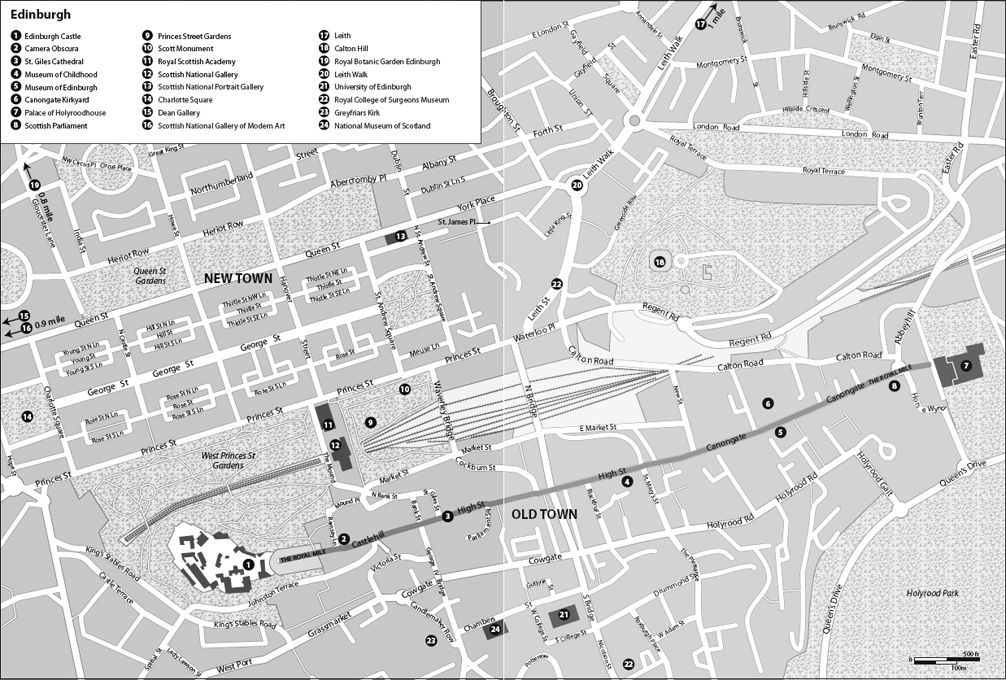

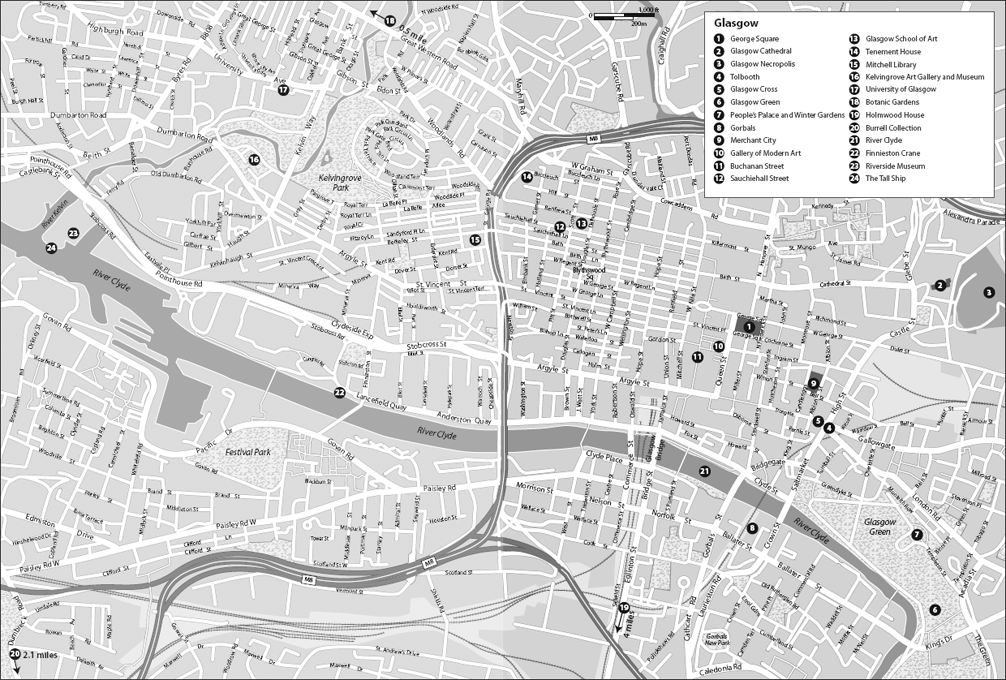

There have been many books about each of these cities, but no one has ever written a serious volume exclusively devoted to both. To do so seems heretical but necessary. It is impossible to live life to the full in either place without occasionally thinking wistfully or smirkingly of the other, and no visitor can understand urban Scotland or the Scottish nation without comprehending these proud competitors. Beloved of tourists, Scotland is a small country of five million people, more than half of whom live in the area surrounding Glasgow and Edinburgh. This book is written for natives and guests alike. A tale of two cities, it focuses on twenty or so visitable sites (usually specific buildings or clusters of buildings) in the historic core of each, and draws from those present-day locations aspects of the character and provenance of their municipality. Every chapter is constellated around several particular spots. The book does not aim to provide a comprehensive historical map, but strives to trace cultural leylines, some familiar, some long obscured.

The central feature here is a multi-chaptered account of each city; the present opening chapter sets out something of the background to their rivalry; at the volumes conclusion a short envoi gestures, optimistically, towards rapprochement. Having given Glasgow priority in my books title, in ordering the contents I have placed Edinburgh first. In matters of arrangement, prioritizing, and protocol, where Edinburgh and Glasgow are concerned it is impossible to get things right. Yet in the midst of each city, when one eyes the surrounding high culture (which is what this book does), such concerns often drop away. Look up! generations of Glaswegian mothers have counseled their children, alerting them to the loftily ornamented Victorian glories of their urban heartland; in Edinburgh, the Castle and other hilltop monuments constantly encourage a raising of the eyes. Visually rich, the centres of both places are best seen on foot. These are not fast-paced metropolises like New York or Hong Kong, but slower, strollable European cities.

Most of this book is arranged sequentially in terms of space, rather then chronology: its core sections progress along streets and through parks. I have cast those chapters mainly in the form of town-centre excursions that use the visible fabric of the cityits built environmentas a gateway into the areas character and past. Architecture can function as social memory, and there are elements of architectural history in what follows; but more of the book concerns the people of each place. These cities are populated by folk with fascinating stories. To let readers relish some of the more notable achievements of the citizens of both places, I have written about women and children, as well as about famous and infamous men. Often, accounts of townscapes give the impression that cities have been lived in almost exclusively by adults; and it has been all too easy in a lot of Scottish historiography to assume that being Scottish means having two Y chromosomes.

Through attending to nodal sites in either place, then, the chapters that follow try to give the reader a sense of each citys history and people. Within the main Edinburgh and Glasgow sections, the principal locations are used often as points of entry into the citys story, and other notable attractions are mentioned in passing. A few chapters, like the one which discusses Glasgows Burrell Collection and Holmwood House, focus on sites that are some distance apart; but often, as in the chapters on Edinburghs Royal Mile, readers are invited to walk the route. I have tried to present an engagingly detailed continuous account, so that anyone who reads the book from start to finish will get a good sense of both cities and their famously scratchy relationship. Museums and galleries, Adam Smith and Walter Scott certainly featurebut so do small apartments, a poetry library, protean Madeleine Smith, and the entrepreneur Maria Theresa Short. Sometimes, partly for the sake of variety, I have chosen to view sites from unusual angles, looking, for instance, at one of Glasgows best-known streets through the eyes of a Victorian child who grew up there, or noting how Edinburgh University was perceived by its most famous student from England. I have sought to mix novelty and familiarity in something like the way each of these great cities does, and to make both places attractive to a reader who may or may not have time to return.

The idea of portraying an entire municipality by means of a panoramic view reproduced inside a large cylindrical surface was first conceived on Edinburghs Calton Hill by Irish artist Robert Barker, who patented the device in 1787 and soon had the temerity to exhibit his depiction of Edinburgh in Glasgow. Based around a particular selection of nodal points, this book cannot provide such a comprehensive wrap-round experience; but it does aim to exhibit revealing glimpses of each city to the other, and to a wider international public. Since Barkers day, each place, like most urban locations, has developed sprawling peripheral housing estates, often with insistent social problems. These, though occasionally alluded to, are not the preoccupation here. In concentrating mainly on city-centre heritage sites that present-day tourists may readily visit, I have adopted a necessarily exclusive focus. My choices can be disputedanother writer might have paid far more attention to football, folksongs, and food, far less to literature, gardens, and murderbut I hope that they work. Centering on permanent places that are open to the public throughout the year, I have given little space to such performance venues as halls and sports-grounds, privileging instead art galleries and historic homes.

Next page

2013

2013