TAKE ON ME

Ole Gunnar Solskjaer the sub from hell.

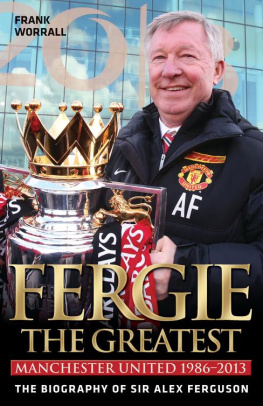

SIR ALEX FERGUSON

H e had scored better goals for Manchester United goals that had won the Champions League and goals that had knocked their bitterest rivals Liverpool out of the FA Cup. Goals that had secured the Premier League title, like the one at Southampton in the season after they had landed the Treble. He had also scored international goals in World Cup games for Norway. The Baby-Faced Assassin they called him, with more hits than the Sopranos; no one ever asked him how much he detested it.

The goal he scored that balmy night, though, in the autumn of 2006 against Celtic in the Champions League was his favourite. It was the first goal he had scored at Old Trafford for over three years, during which his career seemed in ruins. Paul Scholes had snapped up a loose pass from Gravesen and fed Saha; the Celtic keeper Boruc blocked the shot but Ole was on hand to sweep home.

Everyone had conceded that his career was over, even his manager, the man who had discovered him, nurtured him and watch him grow into one of the deadliest strikers in the modern game. Only Ole had believed that he could turn things round; he knew he had not lost his talent or his nerve. That is what drove him on and renewed his determination to achieve a miraculous recovery.

Ole Gunnar Solskjaers winning goal against Celtic at 8.47pm on 13 September 2006 was the high spot of the most remarkable comeback in the modern game. It showed that the years of protracted frustration and pain had not broken him. On the contrary, his greatness as a player was about to flower anew.

Lester Piggott won the Breeders Cup Mile within two weeks of his return to racing following his time in prison. Rocky Balboa made a wonderful comeback in the movies with another blockbuster of a bout; Sylvester Stallone reminded us in his ground-breaking return that it is not how hard you punch but how hard you take a punch that matters. This was never truer than in Oles case. When he scored on that Wednesday evening against Celtic, Old Trafford roared its approval. Uniteds Number 20 thrust his fists triumphantly into the air. This was just like Rocky did on the steps of the Art Museum in Philadelphia, one of the most iconic moments of modern cinema. Oles goal will go down in United folklore in similar fashion.

A few nights later, the late-night news round-up ran the usual depressing film snippets of some of the daily events that make up our 21st-century world a bombing in Iraq, for example, was accompanied by the standard-issue images of death and destruction. Among the onlookers gazing at the burning aftermath of the bombing, the camera lingered on a young boy wearing a red shirt emblazoned with white AIG lettering. Among the carnage, a scrap of normality, a reminder of the global community, and how football has the power to transcend vast differences in ideology and culture. Ole Gunnar Solskjaer is part and parcel of that spirit of genuine sporting endeavour, reaching out to diverse communities around the globe. His efforts, and those of his team, have been hugely appreciated by those who simply love football, and appreciate the spirit and skill with which Ole represents his club and country. As an ambassador for the beautiful game, Ole is an example of all that football could hope for committed, skilful, loyal and blessed with a perpetually youthful image he has become an integral part of the modern history of Manchester United, and a player who has earned respect from fans and footballers alike.

To discover how Ole became this universally-acclaimed global figure, playing for his national team and, arguably, for the greatest club side in the world, we have to travel back in time to 1973, and to Kristiansund, a small town by the coast of More og Ramsdal in the middle of Norway.

Ole was born on 26 February 1973, a year which turned out to be a significant one in world history Britain joined the EEC, the Watergate scandal broke, famine was rife in Ethiopia and the Yom Kippur War erupted following the invasion of Israel by Egypt and Syria. Manchester United at that time were ailing, having dropped stone-like to 18th position in the old First Division. Bobby Charlton played his last game for United at Chelsea, his stunning flood of goals having now dwindled to a trickle.

Bobby was one of the golden triangle of Charlton, Law and Best who had taken United to stellar heights in the late 1960s. Bests once insatiable desire to drink and party had given way to the paranoia and self-loathing that destroyed his glittering career. Within a year, Denis Law, now at Manchester City, was to back-heel the goal that relegated the club and end the fiasco of their declining years. It was the most symbolic goal in the history of both Manchester clubs. Et tu, Brute.

Ole always loved football his team of choice, like many Scandinavian football fans, was Liverpool and particularly scoring goals. His family moved when he was four to Clausenengen and, at the age of seven, he joined his local team with the same name. The youngster liked it so much he stayed there for the next 15 years.

Liverpool at that time were the team of the subsequent decade with a galaxy of star names. The men from Anfield went on to dominate the league in a similar fashion to Manchester Uniteds stranglehold of the 1990s. Just like today, all the top English games were shown in Norway and the public followed them with great interest. Oles favourite players were the heroes he saw on TV at the time, with Kenny Dalglish, the Liverpool superstar, a particular favourite of his. The Scottish international was the first player to score 100 league goals on both sides of the border. Commentators subsequently noted some similarities in style between the two, particularly the bewitching footwork and icy coolness in front of goal.

Both were very stylish players and deadly goalscorers. One of Oles earliest football memories was watching Dalglish on TV scoring the goal that retained the European Cup for Liverpool in 1979. It was a wonderful, deft, first-time chip with just enough power to find the far corner of the net. In his back garden, young Ole would spend hours practising and developing his own football technique. One of his favourite party pieces was to stab down on the ball to refine the chip reminiscent of King Kennys against Bruges. Little did he realise that the skills he was perfecting would one day help him score the winner in the most prestigious Cup competition in Europe.

Other heroes of Oles were Marco van Basten, the Dutch superstar striker, whose wonderful career was derailed by an ankle injury, and Zico, the Brazilian ace.

Another vivid memory of Oles was of the 1982 World Cup played in Spain. Although they went out to eventual winners Italy, the Brazil side were one of the most attractive teams to ever grace the World Cup. Their style and panache captured Oles imagination and made a lifelong impression on him.

The football stickers and bubble-gum cards of soccer stars of that time were avidly collected by Ole and traded with his chums at school. Oles favourite cards were of the Liverpool players, particularly in different strips. His most prized was one of Kenny Dalglish in the 1981/82 all-yellow away strip with the liver bird badge.

In an interview with the Manchester United fanzine Red News, Ole discussed the somewhat sensitive subject of the fact that he was a Liverpool fan as a youngster. You know, when you are back home and you watch games on TV and you tend to support the team that is winning, so in the 80s Liverpool were winning. Kenny Dalglish, he was the best player I thought, then Marco van Basten and Zico but, in England, Liverpool won so you get caught up in the moment.