ALSO BY JONATHAN D. SPENCE

The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci

The Gate of Heavenly Peace:

The Chinese and Their Revolution, 18951980

The Death of Woman Wang

Emperor of China:

Self-Portrait of Kang-hsi

To Change China:

Western Advisors in China, 16201960

Tsao Yin and the Kang-hsi Emperor:

Bondservant and Master

F IRST V INTAGE B OOKS E DITION , SEPTEMBER 1989

Copyright 1988 by Jonathan D. Spence

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published, in hardcover, by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, in 1988.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Spence, Jonathan D.

The question of Hu/Jonathan Spence.1st Vintage Books ed.

p. cm.

Bibliography: p.

eISBN: 978-0-307-79381-2

1. Hu, John, 18th cent. 2. Converts, CatholicChinaBiography. 3. Foucquet, Jean Francois, 1665-1741. 4. Mental illnessFranceHistory18th century. I. Title.

[BX4668.H82S66 1989]

909.7092-dc20

[B]

89-40102

v3.1

FOR

Colin and Ian

Contents

Heureux qui, comme Ulysse,

a fait un beau voyage

Joachim du Bellay

Acknowledgments

The idea for this book came to me on the night train from Pesaro to Florence. However, I could never have had the idea had I not reada year or so beforethe erudite and absorbing study on Father Jean-Franois Foucquet, S.J., written by Professor John Witek, S.J., of Georgetown University. Near the end of that study, Professor Witek gives a brief summary of the problems that arose between Foucquet and Hu and it was this that my brain, unwittingly, had retained. When I returned to the United States, Professor Witeks meticulous footnotes led me first to the relevant printed materials and thence to the archives in three countries, while his courteous response to some early queries quickened my resolve to complete the quest. I am deeply grateful to him.

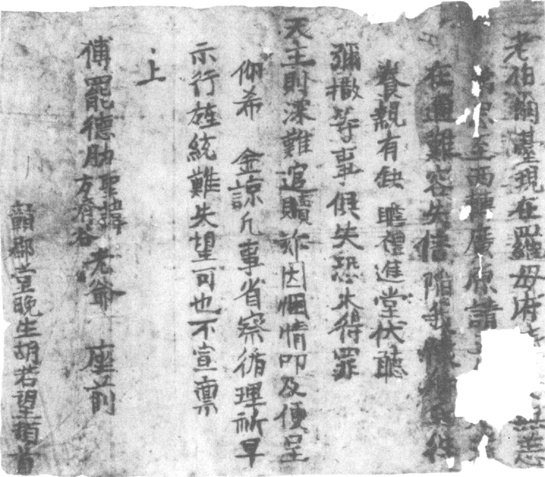

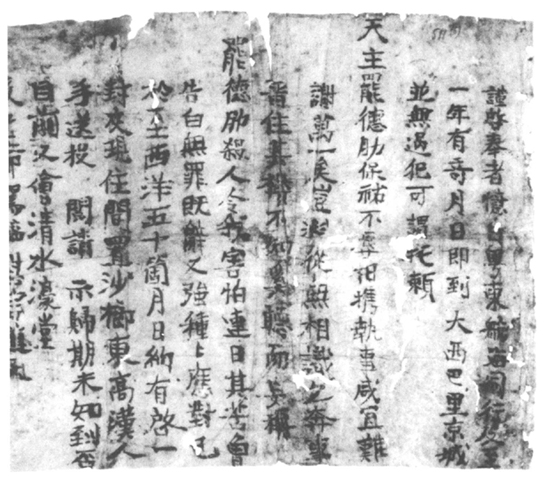

My thanks, too, to many other scholars who replied swiftly to my requests for bibliographic help: Robert Dietle, John Merriman, Natalie Zemon Davis, Emilia Viotti da Costa, Grace Goldin, Theodore Foss, W. J. Bynum, Robert Schwartz, Robert Darnton, Laurence Winnie, Joanna Waley-Cohen, and Peter Brooks. For help in attempting an at least fairly lucid translation of John Hus distraught letter of 1725, I am sincerely grateful to Chen Jo-shui, Chin Annping, Wu Chen-liang, and Y Ying-shih.

Portions of this book were first presented as part of the Morgan lecture series at Dickinson College in Pennsylvania, in the fall of 1987; others were presented as segments of the Christian Gauss seminars at Princeton University, and of the Lax Memorial Lecture at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts.

Isabel Smith helped me with her advice at a crucial stage in the formation of the Charenton chapters. Karin Weng brought typewritten order to the patchwork of my drafts, as Florence Thomas did to my revisions. Both Harold Bloom and John Hollander gave a careful reading to the penultimate draft. To all of these generous people, my thanks.

In pursuit of Hu I traveled to many of the places where he had been before me, to Canton and Bahia, to Port Louis, Vannes, and the Maison Professe in the Marais, as well as to the site of his former hospital in Charenton, now separated by an eight-lane freeway from the dark waters of the River Marne. In all these places I found protective presences, and I would like to thank them here. I would also like to thank the archivists and their staffs who helped me on so many occasions as we grappled with their aging treasures for traces of Hu: in Paris, at the Archives Nationales, the Archives des Affaires Etrangres, the Bibliothque Ste. Genevive, and the Bibliothque Nationale; in Rome, at the Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana; and in London, at the British Library and the Oriental Manuscripts Depository. The directors and staff at the Psychiatric Institute and the Hpital Esquirol in Charenton, and at the Wellcome Institute of the History of Science in London, were similarly helpful.

As with all my previous books, Yales splendid collections and their keepers hastened my task at every moment. As with all my previous books, too, my wife, Helen Alexander, had to take the full force of the aloneness that always comes over me as I write. For the fourth time, now, Elisabeth Sifton served as my careful and caring editor, with that special enthusiasm that only her authors know. And just in case all that love and caring from so many people might not prove enough, my aged dog Daisy climbed the narrow wooden steps to my summer study countless times a day, and lay across from me during every word, sighing gently in her sleep over my endless attempts to draw some meaning out of the constantly vanishing past.

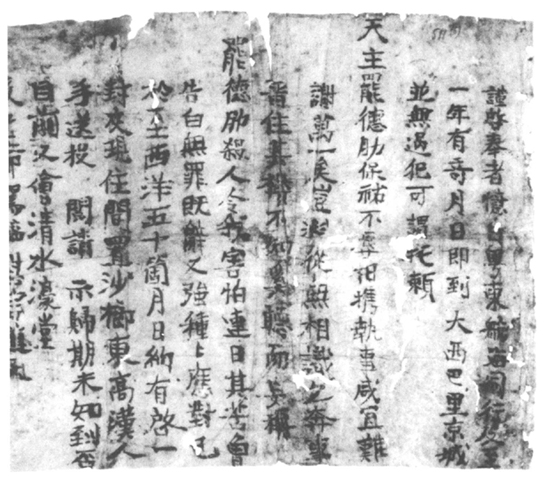

Courtesy of the Vatican Archives

Letter from John Hu to Father Foucquet, October 1725

Preface

Perhaps the most astonishing thing about Hu is that we know anything about him at all. The Chinese biographical tradition is rich in the materials it has preserved on scholars and statesmen, philosophers and poets, men of unusual moral rectitude and recluses distinguished by their eccentricity. Even merchants might be recorded if they were both wealthy and charitable, and soldiers if they guarded the borders with valor or suppressed indigenous revolts. But Hu was none of those things. He was an exasperating and apparently unprepossessing man, who had very little money, no distinguished relatives, and only a perfunctory education that left him equipped for nothing except the copying of other peoples texts. He had courage, but no skills in warfare. A convert to Catholicism, he never rose high in the ranks of the Church. And though he did travel once to Europe, in 1722, and stayed there over three years, much of the time in a madhouse, he wrote only two brief letters about his experience, and one of those was lost in transit.

Yet very considerable detail about Hu is now preserved in three of the worlds great archival collections: the Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana in Rome; the British Library in London; and the Archives des Affaires Etrangres in Paris. The main reason for the survival of these materials is the guilty conscience of the man who brought Hu from Canton to Europe in 1722, the Jesuit Father Jean-Franois Foucquet. After Hu returned from France to China, in 1726, blurred rumors began to swirl in both Paris and Rome that Foucquet had, in various ways, treated Hu shabbily. Desperate to preserve his good namehe had only recently been elevated to a bishopricFoucquet wrote a long account of his relationship with Hu and circulated it among a select group of friends and senior churchmen. Foucquet called his account the Rcit Fidle, which can be translated as True Narration. One copy entered the hands of the Duc de Saint-Simon, the celebrated chronicler of the reign of Louis XIV and a friend of Foucquets, whence it passed with the rest of Saint-Simons papers to the French National Archives. One copy somehow reached the open market later in the eighteenth century and was given to the British Library by a donor in the nineteenth century. One copy was handed over to the papal archives, along with the rest of Foucquets unpublished writings, his journals, and his letter books, presumably after his death in 1741.