CONTENTS

Guide

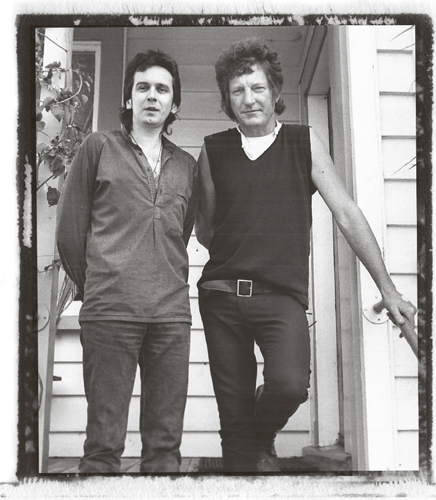

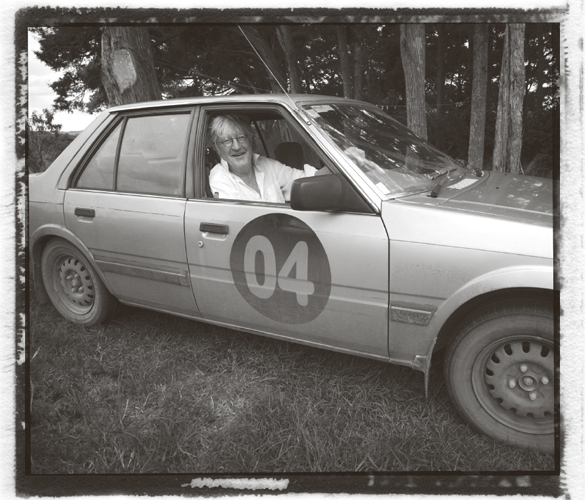

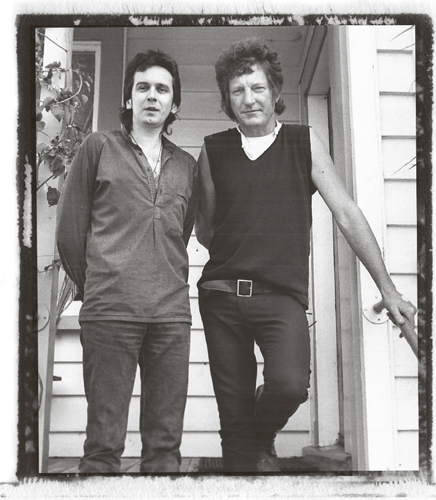

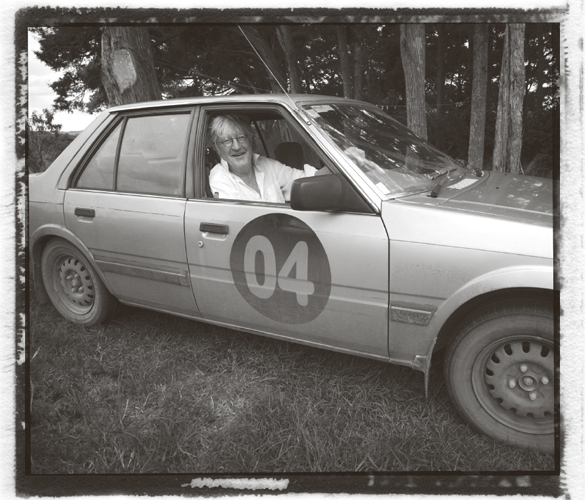

Writer and subject, for Angel Gear, 1989

PICTURE: GIL HANLY

Though leaves are many, the root is one;

Through all the lying days of my youth

I swayed my leaves and flowers in the sun;

Now I may wither into the truth.

The coming of wisdom with time, W.B. Yeats

I spot Sam, parked up outside the Four Square in the main street of Kaiwaka in his dusty old gold Mazda 626. The car and its famous contents would be almost invisible in this small-town Northland spot were it not for the bold racing-style 04 painted on the Mazdas front doors. Sam doesnt get out to greet me as he sees my car approaching, but pulls out of his park and turns onto a backroad out of town, me on his tail as he boots his elderly car up into low hills and rolling farmland.

Each time, meeting up with my old friend still feels like the start of another adventure, probably because usually it is. Anything could happen and often it does.

Sam cuts a sharp right off the road, whips through a farm gate and on we drive for a good stretch, up and down over rolling land, eventually pulling up outside a farmhouse where Sam unravels from his car and strides over to greet me with a hug. As always, its like grappling with a tall, amiable bear.

Five hours, a longish lunch and a certain amount of fun later, were twenty kilometres away, upstairs in Sams house which is a house thats all upstairs anyway and we are very well oiled indeed, discussing the meaning of life, which we both reckon weve been close to discovering, though never quite at the same time.

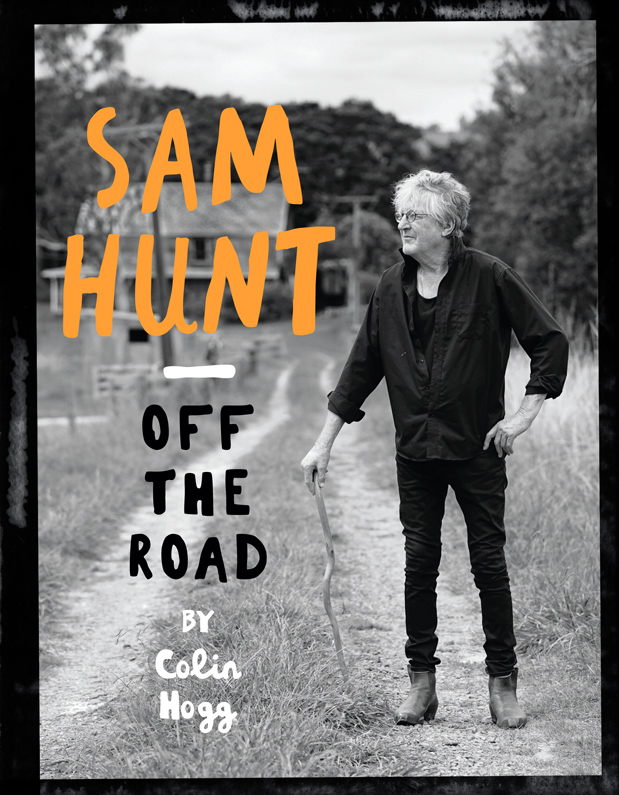

Around thirty years ago, I wrote a book about Sam, who was then, as the saying goes, in his prime, as was I, four years younger, which is still the situation. The book was called Angel Gear: On the road with Sam Hunt and it was the start of something that hasnt ended yet. Well, not just yet, though the road bit might be over. For Sam anyway.

Were talking about doing a new book, some sort of follow-up to that other one, based on a series of conversations with a little more focus than our usual conversations. And, as is the way with these things, the moment you talk about writing a book is the moment the book starts. There are no edges. Its all joined up. Its all the same song.

Sam, straightaway taking the situation to technological extremes, thinks I should immediately be recording everything we say. For the record, he mutters mysteriously, though that might be the three bottles of red wine talking. Its hard to say. Im operating under handicap myself.

I thought Id just take notes, I tell him. Ive had a few beers by now.

Youll be too drunk, he says. It could feel like he doesnt trust me, but of course he does. Who else could he trust? Theres almost no one else left, though there is his little circle of good local friends in these parts and there is also Hugh Rennie, QC, Sams old barrister friend, who has kept irons in and out of fires over the years for Sam. Its good to have a pal whos a lawyer. And its good to have a pal whos a poet, though its a great deal more challenging.

Well Im not recording this meeting, I tell him, firmly I hope. This meeting is just to talk about it, how well do it.

Its too late. Its already started, he says and, of course, hes right. But we both get really hammered this time, countless joints shared, me on a string of strong craft beers, Sam on the rugged red wines, four bottles of the stuff down by half past five and Sam just about down with them.

It seems too early to collapse, I hear myself say and, perhaps in response, Sam revives, as he often still does when lesser mortals would be stiff on the floor. My only defence in these circumstances when, over-excited by the sum of our parts, we drink too much, is to avoid drinking the wine.

I dont know how Sam survives the stuff. He currently favours rustic Chilean reds, ox-blood dark, half an inch of sediment at the bottom of the bottle. His lips turn blue from drinking it, and his teeth become alarmingly iridescent in the late-afternoon light.

We both make less and less sense till eventually we make no sense at all. But the only time we ever really made any practical sense together was when we were out on the road with a job to do, Sam performing, me attending to him with a chaotic confidence I might have picked up from him in the first place.

Off the road, all these years later, is a bit of a different deal. Back then, we were still doing some things for the first time, certainly for the first time together. And I was writing a book about it, which was a first time too.

Also, I didnt really know Sam then, so we were going through all that, figuring out where we fitted with each other, if we fitted at all. And its not entirely an easy or a given thing to fit with Sam Hunt. He takes up a lot of space. Hes the centre of every scene. Rooms change when hes in them, deflate when he leaves.

Hes unforgettable and a bit overwhelming. And, it almost goes without saying, poems fall from him like leaves from a tree, which in some ways is something he resembles. He once fancied himself a cabbage tree, though as I might have pointed out to him, a cabbage tree isnt a tree at all, but a giant lily, and I felt Sam would not like to think of himself as a big flower, though in a way thats just what he is.

Theres a tough side too, though, because one of the other notable things that marks him out is that he has had to fight to be himself and hes had to fight to stay himself, carry himself in a gidday world, defend himself and, quite a lot, hide himself.

Being highly, almost unnaturally, recognisable in a small country is one of those things that is a gift one day and a curse the next. The average New Zealanders egalitarianism can be a pain in the arse sometimes, though Sams never averse to telling a passing pesterer to piss off, and probably in stronger terms than that.

And that doesnt always make things better. I remember one time in a pub car park in Hamilton when it made things much worse, but I think we felt indestructible in those days. And, so far, we have been, though, as Sam likes to point out, it cant last.

(FROM ANGEL GEAR)

I ts 7.45 a.m., Tuesday 9 August. A misty morning with the hint of a big ghost of a sun behind. I rang Sam last night to ask him to meet me at the Hamilton Railway Station. He sounded ebullient. Loves the new Dylan album (Down inthe Groove). Hardly surprising.

Itll take a lot of gentle persuasion to convince me, I tell him.

Ive got plenty of gentle persuasion with me, he bellows back.

The taxi driver taking me to Auckland Railway Station is a fallen Marxist. Were all left to die in the gutter, while those fucking politicians... Thank Christ were not going all the way to the airport. Who needs it at this time of day? An hour later my train is snaking south, finally free of the endless ugly grip of South Auckland, cutting like an eel through the rolling green sea of farmland.

Theres good news in the paper six hundred real estate agents have been made redundant in the last year. The Heralds 100 Years Ago column has a piece on the exhumation of Beethovens remains, which reveals that after his death, in 1827, both his ears and aural cavities were removed so that someone could study the cause of his legendary deafness. They were each placed in a glass jar full of spirits of wine. The jars disappeared. Wonder where Beethovens ears are now?

Next page