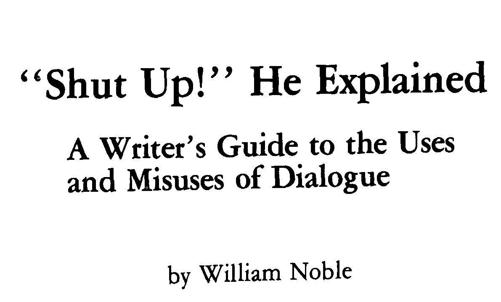

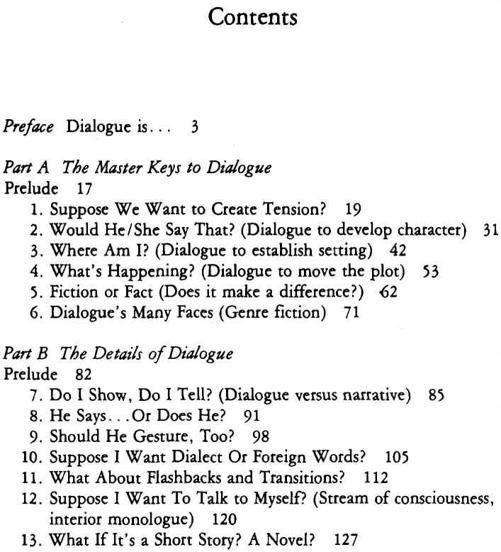

William Noble - Shut Up! He Explained: A Writers Guide to the Uses and Misuses of Dialogue

Here you can read online William Noble - Shut Up! He Explained: A Writers Guide to the Uses and Misuses of Dialogue full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1991, publisher: Paul S Eriksson, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Shut Up! He Explained: A Writers Guide to the Uses and Misuses of Dialogue

- Author:

- Publisher:Paul S Eriksson

- Genre:

- Year:1991

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Shut Up! He Explained: A Writers Guide to the Uses and Misuses of Dialogue: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Shut Up! He Explained: A Writers Guide to the Uses and Misuses of Dialogue" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

William Noble: author's other books

Who wrote Shut Up! He Explained: A Writers Guide to the Uses and Misuses of Dialogue? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Shut Up! He Explained: A Writers Guide to the Uses and Misuses of Dialogue — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Shut Up! He Explained: A Writers Guide to the Uses and Misuses of Dialogue" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

A friend called one day. "Someone I've known for thirty years sent me a manuscript," he said. "A fascinating story. You'll love the plot."

"A published writer?" I asked.

"She sets the story in Charleston, South Carolina, at the turn of the centurythe old South embracing the Industrial Revolution, black-white love interests...." My friend paused. "She's always wanted to write."

Unpublished, I thought. "You want me to look it over."

"I know you're busy."

"Did you enjoy reading it?"

"She's a social workershe understands people."

"You think it might go?"

"I'd really appreciate your thoughts...."

The manuscript arrived two days later, neatly bundled, with the barest note from my friend. Three hundred and forty typewritten pages, centered properly; a prefatory statement and a brief background on the author. I began reading.

And by page fifteen I knew the manuscript had no hope. The storyline was interesting, the characters richly endowed, the historical perspective clear and accurate.

What happened?

This happened: on page four the young hero's superior says to him,

"Talk to Harrison, show him what's here, then call me."

"Yes sir."

"You know what's here?"

"Yes sir, I think so."

"Are you sure?"

"Yes sir."

On page six:

"Good morning, Mr. Harrison."

"Good morning."

"Would you like to see some samples?"

"Yes."

"They are over here, sir."

"Oh, they are, are they?"

"Yes sir."

On page fifteen:

"Is Harrison here?"

"Yes sir."

"Good morning, Mr. Harrison, have you seen the samples?"

"Your young man has been showing them to mewhat's your name again, son.

And so forth.

Dialogue. This is what tripped the author and turned what could have been an interesting story into one that barely plods. Dialogue must move a story , Peggy Simpson Curry wrote more than 20 years ago, and when it doesn't, everythingstoryline, character development, mood enhancementgrinds to a halt.

Let's be clear about one thing, though: dialogue is one of the most difficult skills for any writer to master. The sense of reality to be conveyed is often misunderstood because we're dealing with an essential sleight-of-hand. What is, is often not enough, just as what passes as fact is not the same as truth. Dialogue

must not only be factual, it must be dramatically factual, and in this way the writer must convey not so much what is said as the sense of reality, spiced dramatically.

In the passages of dialogue by the social worker-author, we can't deny the evident conscientiousness. She has faithfully recorded each conversation.

The reader's reaction isso what?

The writer will probably respond:

- That's the way people talk.

- Those are his exact words.

- That's the way it happened.

Maybe, but it doesn't make a story. Here's Samuel Johnson, more than two hundred years ago:

Tom Birch is as brisk as a bee in conversation, but no sooner does he take a pen in hand, than it becomes a torpedo to him, and benumbs all his faculties.

Conversation, then, is not dialogue. And when we insert conversation on the written page assuming it is good, realistic dialogue, it's like throwing cold water on whatever drama we are building. Conversation is...conversation; dialogue is dialogue. They are easy to mix up and hard to separate.

But the diligent writer perseveres. He or she knows what will crackle on the written page, and what will die.

"Where do you live?"

"230 State Street."

That's conversation.

"You live around here?"

"If you want to call it living."

That's dialogue.

In some respects good dialogue-writing is a mirage. It seems to be realistic, it seems to portray actual people doing actual things.

But it doesn't. Not really.

Here's Geoffrey Bocca from his book, You Can Write a Novel:

Of all aspects of novel writing, none plays a greater con

job on the reader than dialogue. The art of dialogue lies in leading the reader to think that the characters are speaking as they do in everyday life, when they are doing nothing of the sort. What people speak in normal life is conversation, not dialogue. Conversation is exchange of information: 'What's the time?' 'Six o'clock'. That's conversation, but it is not dialogue.

Then what is dialogue? Perhaps the answer is more elusive than we might think. We can say what it is not , and that might be a good deal easier than artificial rules to define what it is. But we do know certain things: we recognize good dialogue when we read it, we're grabbed and shaken by its veracity. Is there any doubt that the following passage from John O'Hara's Ten North Frederick sparkles as dialogue?

"What do you think I've had you in my office for? To talk about baseball?"

"No sir."

"Then answer my question."

"Which question, sir? Gosh, you ask me a thousand questions, and I don't know which I'm supposed to answer.''

"There's only one question. Are you guilty of smoking cigarettes in the toilet and endangering the property, the lives and property of this school?"

"I smoked. You know that, sir. I was caught."

Perhaps like a beautiful woman or a mystical experience, good dialogue is easier to recognize than it is to define. But there are certain guides we can follow: good dialogue will do each of the following:

- characterize the speaker;

- establish the setting;

- build conflict;

- foreshadow,

- explain.

For example, suppose we want to show a character's cynical

nature. A physical description will hardly do it, and if we call the person cynical, it certainly loses something in dramatic effect. So we put words in the character's mouth:

"Life's a bitch, man."

or

"I never trust a man who parts his name to the left. He's hiding something."

Here's John O'Hara again. A judge and lawyer are talking informally, and the judge suggests that a recently widowed female friend hire a young, bright, fresh lawyer, set him up in practice, and use him as a stud. The judge continues:

"...I'm telling you, it's a fair bargain. All she does is support him till he gets established. Why is it so much worse for a young guy to sleep with an elderly woman than a young girl to go to bed with an elderly man? You look around this club. You know yourself, half the members of this club are giving money to young girls for some kind of satisfaction."

"Half? That's pretty high."

"Arthur, your own friends are doing it, and you know it."

"No, I don't know it," said McHenry. "I suppose there are two or three..."

Now there's a cynical man, and O'Hara paints him through the use of his own words. The essence of his cynicism is furthered by the contrast with the other speaker who is certainly more forgiving. The two sides of the equation demonstrate character traits in both men, and we get to know them each a little better.

Dialogue in a vacuum, however, serves little purpose. A character saying something for no reason or without adding to the story wastes the reader's time and patience. It's like inserting an unwanted ingredient into a carefully orchestrated mealit can have the effect of contaminating everything. Anthony Trollope said that dialogue must contribute to the telling of the story and that when extraneous matter is added the reader feels cheated. Arturo Vivante agrees. "There should be a nexus, link or connection between one line and another. The dialogue should make a point. The gist of it, its purport, should come through."

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Shut Up! He Explained: A Writers Guide to the Uses and Misuses of Dialogue»

Look at similar books to Shut Up! He Explained: A Writers Guide to the Uses and Misuses of Dialogue. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Shut Up! He Explained: A Writers Guide to the Uses and Misuses of Dialogue and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.