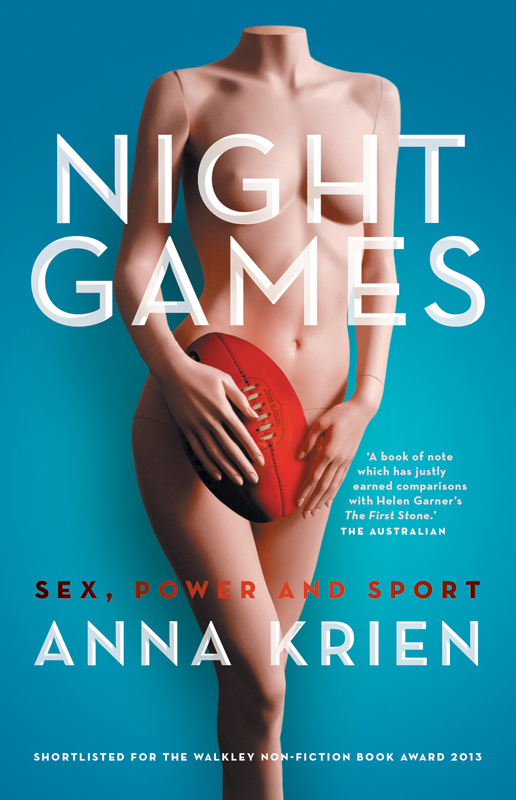

I have changed the name of the defendant in the following account of a rape trial. On grounds of confidentiality I am not permitted to give the complainants name, and in fairness I believe the defendants name should be suppressed here for the same reason. Several other names have also been changed.

As is customary in rape trials, the complainants evidence was given in closed court and cannot be reported.

PROLOGUE

When the members of the jury ten men and two women emerge from the back room, they dont look at him. Their eyes do a darting sweep of the court, lifting up and over our outlines. The defendants seats are full, the complainants seats behind the prosecutor except for a lone policewoman who has arrived to hear the verdict are empty, as they have been since the beginning of the trial, and the press seats where I am are largely vacant.

Five days ago there had been barely any standing room as the reporters crammed in, opening and shutting the door in the middle of proceedings. A star footballer had arrived to give evidence. The Collingwood player took the stand jauntily, swinging a little in his chair as he spoke.

Today its just an ordinary man in the dock, his face grey with dread, eyes rimmed red, no big deal as far as headlines are concerned. Hes not a footballer at all, the judge and prosecution had agreed before the jury was selected and the trial commenced. I turned to look at Justin Dyer then. Disbelief flickered across his face. Hed been dropped from his team in the Victorian Football League after the charges were laid.

No, hes a hanger-on, said the prosecution.

Exactly, said the judge.

Have you reached your verdict? the judge now enquires. The foreman of the jury nods and stands up. The 23-year-old in the dock is answering to six counts: one of indecent assault, the rest rape.

Not guilty.

Justin buckles and lets out a huge wracking sob. His gasps seem to heave over his cordoned-off area, over the wooden banister, to his family. They let out a choking sound. The jury foreman trails off, looking at the man in the dock, the document in his hand shaking.

The judge nods at him to continue, and with each verdict of not guilty the sobbing grows louder, the family now holding themselves, arms crossed over one another, as if forming a kind of dinghy on a rough sea and taking the waves of Justins gasping as their own.

The jury members shift in their seats, fiddling with their hands, with the rings on their fingers, stealing wide-eyed looks at the dock. It is as if they are seeing Justin for the first time.

With my fingers, I try to push my own tears back into the seams of my eyes. I squeeze my nails into my palms, etching the skin, for distraction. The solicitor for the state, bringing to the court the charges initiated by Sarah Wesley, the complainant, sits facing the court. She exchanges a long, knowing look with the policewoman in the front row behind the Crown prosecutor.

As the jury is thanked and dismissed, I stare at my notepad. Now they know the difference between what is said in popular media and reality, the judge says of the jurors to the lawyers. We all try to ignore the whirlpool of emotion in the corner of the room.

After the judge departs, the reporters stand awkwardly at the door, leaving for the family to settle, to sort themselves out and start leaving so they can ask for a quote or two. I stand with them, but I dont really belong. I know this family now. Ive sat with them outside for the past three weeks, waiting with them in that dead space. I put my pencil and notebook away, take a deep breath and cross over the empty seats into this flooding family on the defendants side.

His grandmother envelops me in a hug and I think, well, there goes my objectivity. And Im struggling with this. Its as if Im inside out. The journalists at the door, their faces are unreadable, they have cool exteriors. I admire their poise, their unmuddied positions, absolved in their detachment. Its all backwards for me. Because despite the verdict, I still dont know who is guilty and who is innocent, and yet here I am, hugging the grandmother in the defendants corner, and thats a problem, dont you think?

PART 1

THE FOOTY SHOW

CHAPTER 1

Much like the federal election of 2010, the Australian Rules Football grand final that year was a draw. It was an unfathomable concept for players and spectators: how do you party when there are no winners and no losers? Then, to the delight of pubs, merchandise sellers and sausage makers, the Australian Football League announced a rematch between Collingwood and St Kilda. The Pies beat the Saints and the city of Melbourne was still cloaked in black and white crepe paper when the rumour of a pack rape by celebrating footballers began to surface. By morning, the head of the Victorian sexual crimes squad confirmed to journalists that they were preparing to question two Collingwood players, the young recruits Dayne Beams and John McCarthy. And so, as police were confiscating bedsheets from a townhouse in Dorcas Street, South Melbourne, the trial by media began.