Scribner

A Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Copyright 1997 by Thomas E. Ricks

Afterword copyright 2007 by Thomas E. Ricks

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

Scribner and design are trademarks of Macmillan Library Reference USA, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, the publisher of this work.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ricks, Thomas E.

Making the Corps/Thomas E. Ricks.

p. cm.

Includes index.

1. United States. Marine CorpsMilitary life. I. Title.

VE23.R5 1997 97-25174

359.9'6'0973dc21 CIP

ISBN-13: 978-1-4165-5974-0

ISBN-10: 1-4165-5974-4

Visit us on the World Wide Web:

http://www.SimonSays.com

To my wife, Mary Catherine

A N OTE ON S OURCES

This is a true book. No names have been changed. Much of what is reported here was witnessed firsthand. Some of it was related later, usually by several participants and observers, but always by at least one person present. A few events were videotaped. I also have relied on the log of Platoon 3086 and other documentation, such as Recruit Incident Reports filed after unusual occurrences, and each recruits continuously updated Recruit Evaluation Card.

C ONTENTS

C HAIN OF C OMMAND

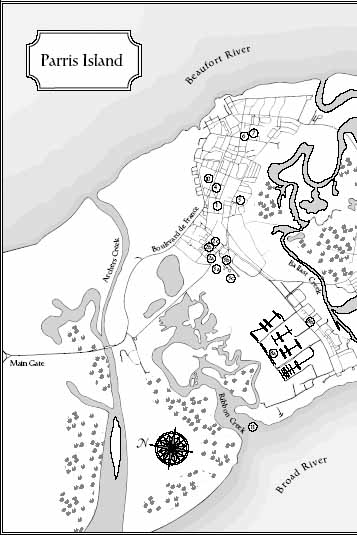

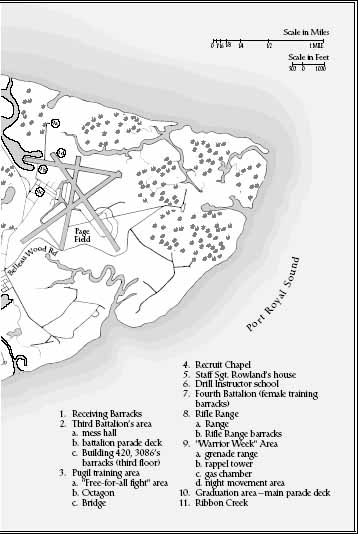

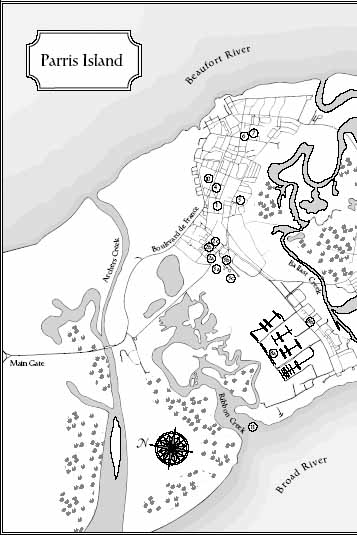

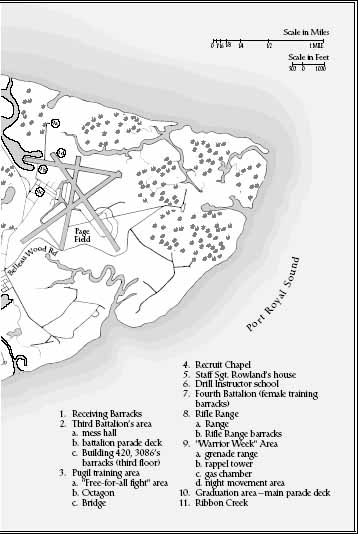

Platoon 3086, Kilo Company, Third Battalion, Recruit Training Regiment, Marine Corps Recruit Training Depot, Parris Island, S.C., as of March 1995:

Drill Instructors for 3086:

Senior Drill Instructor: Staff Sgt. Ronny Rowland

Heavy Hat: Sgt. Darren Carey

Third Hat: Sgt. Leo Zwayer

Series Commander (for Platoons 3084, 3085, and 3086):

Lt. David Richards

Series Senior Sergeant: Gunnery Sgt. David Camacho

Kilo Company Commander: Capt. Jeffrey Chessani

Kilo Company Senior Sergeant: 1st Sgt. Charles Tucker

Third Battalion Commander: Lt. Col. Michael Becker

Recruit Training Regiment Commander:

Col. Humberto Rodriguez (Succeeded soon after 3086s

graduation by Col. Douglas Hendricks)

Depot Commander: Brig. Gen. Jack Klimp

Depot Senior Sergeant: Depot Sgt. Maj. Harold Moore

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers; For he today that sheds his blood with me Shall be my brother. Be he neer so vile, This day shall gentle his condition; And gentlemen in England now abed Shall think themselves accursed they were not here.

Shakespeare, Henry V , IV, iii

PROLOGUE

M OGADISHU ,

D ECEMBER 1992

T his book is mainly about Marine boot camp at Parris Island, South Carolina, but it has its origins on the other side of the world. For me, the story begins on a dark night in Somalia in December 1992, just a few days after U.S. troops landed.

It was my first deployment as a Pentagon reporter. I flew nonstop from California to Somalia in a huge Air Force cargo plane that refueled twice in midair. I didnt know what I was doing, but I realized soon after I stepped into the humid dawn at the ruined airport that I was in a miserable situation. By the end of my first day in Mogadishu I was worried, scared, tired, and a bit disoriented. I hadnt known enough to pack sunglasses and a hat, but I did bring the most essential tool, a big two-quart canteen, which I soon learned to drain at least three times a day.

It was a confusing and difficult time for the U.S. military: Americans had been brought to this dusty but sweaty equatorial nation to help with the logistics of famine relief, and there now was shooting going on. This was the first U.S. brush with peace-makinga new form of post-Cold War, low-intensity chaos that is neither war nor peace, but produces enough exhaustion, anxiety, boredom, and confusion to feel much like combat.

I went out on night patrol in the sand hills just west of Mogadishu with a squad from Alpha Company of the 1st Battalion of the 7th Marines. The city below was dead silent. There were no electric lights illuminating the night, no cars moving, no dogs barking at the patrol, no chickens clucking. The only sound in the night was the occasional death-rattle cough of sick infants. As we walked in single file, with red and green tracer fire arcing across the black sky over the city, I realized that I had placed my life in the hands of the young corporal leading the patrol, a twenty-two-year-old Marine. In my office back in Washington, we wouldnt let a twenty-two-year-old run the copying machine without adult supervision. Here, after just two days on the ground in Africa, the corporal was leading his squad into unknown territory, with a confidence that was contagious.

The next morning I walked to the Mogadishu airport along a hot road ankle deep in fine dust with another returning patrol from Alpha Company, led by Cpl. Armando Cordova, a precise-seeming man with a small mustache and wire-rimmed glasses. A native of Puerto Rico who was raised in the Bronx, he once left the Marines and then, after ten months back in New York City, reenlisted. You dont make friends in the world like you do here, he explained, his M-16 slung horizontally across his chest. We are like family. We eat together, sleep together, patrol together.

The last thing I wrote in my notebook as I flew out of Somalia was that in an era when many people of their age seem aimless, these Marines know what they are about: taking care of each other. Of course, that ethos isnt always honored. Some Marines rob and beat one another, or lie to Congress, or rape Okinawan girls. But over the last four years in Somalia, in a snipers nest in Haiti, aboard amphibious assault ships in the Atlantic and the Adriatic, and at Marine installations in the U.S., I consistently have been impressed by the sense of self that young Marines possess.

The U.S. military is extremely good todayarguably the best it has ever been, and probably for the first time in its history, the best in the world. It also has addressed in effective ways racial issues and drug abuse, problems that have stymied the rest of American society. At a time when America seems distrustful of its young males, when young black men especially are figures of fear for many Americans, the military is a different world. As the sociologist Charles Moskos has observed, it is routine in the military, unlike in the rest of the nation, to see blacks boss around whites.

But the Marines are distinct even within the separate world of the U.S. military. Theirs is a culture apart. The Air Force has its planes, the Navy its ships, the Army its obsessively written and obeyed doctrine that dictates how to act. Culturethat is, the values and assumptions that shape its membersis all the Marines have. It is what holds them together. They are the smallest of the U.S. military services, and in many ways the most interesting. Theirs is the richest culture: formalistic, insular, elitist, with a deep anchor in their own history and mythology. Much more than the other branches, they place pride and responsibility at the lowest levels of the organization. The Marines have one officer for every 8.8 enlistees. That is a wider ratio than in any other servicethe Air Force, at the other end of the spectrum, has one officer for every 4.2 enlistees.