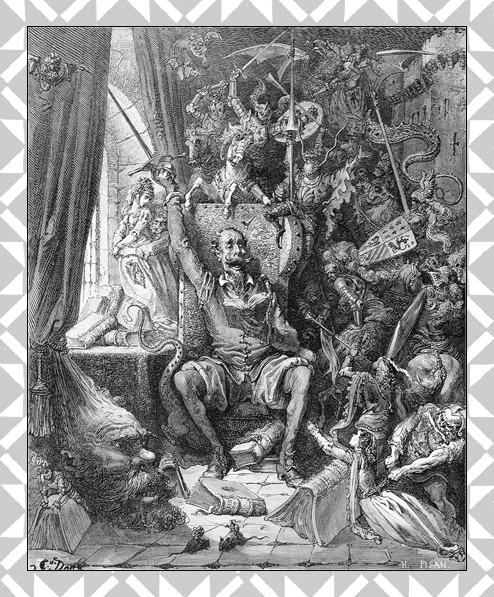

Quixote

Copyright 2015 by Ilan Stavans

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Chris Welch

Production manager: Devon Zahn

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Stavans, Ilan.

Quixote : the novel and the world / Ilan Stavans. First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-393-08302-6 (hardcover)

1. Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de, 15471616. Don Quixote. 2. Cervantes Saavedra, Miguel de, 15471616. Don QuixoteInfluence. I. Title.

PQ6352.S73 2015

863'.3dc23

2015013784

ISBN 978-0-393-24838-8 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House,

75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

Such is my lifelong obsession with this subject that it feels as if it has taken me more than four hundred years to write Quixotesince the First Part debuted in 1605.

At Norton, my heartfelt gracias to Alane Salierno Mason, whose passion for translation of world literature is a touchstone benefiting us all, and who saw the seed for this volume in 2001, upon reading a special issue of Hopscotch: A Cultural Review. I cherish her friendship as well as her savvy, intelligent editorial touch. I wrote a first version of this book, and upon completion, I understood, in conversation with her, that it was the wrong book. So I rewrote it from scratch.

Denise Scarfi, at one time Alane Masons editorial assistant and now a school teacher at a Spanish-English dual-language school in the Bronx, meticulously read the second version of the manuscript, graciously offering her insights. Mary Babcock did an exemplary copy-editing job. Kay Banning was in charge of the index.

Thanks to my tireless Amherst College assistant, Mariela Figueroa, for the countless ways in which she helped bring this volume together. My former student Irina Troconis, who went on various research missions, was also an invaluable resource. And I benefited from the help of four other assistants: Derek Garca, Rebecca Pol, Heather Richard, and Federico Sucre.

The Cervantes industry has been a topic of mine for years. Its impossible to thank the countless people with whom I have engaged in conversation, real and imaginary. Among them are Paula Abate, Jennifer Acker, Vernica Albin, Lalo Alcaraz, Frederick Aldama, Rene Alegra, John Alexander, Frederick de Armas, Diana de Armas Wilson, Harold Augenbraum, David Bellos, Silvia Betti, Harold Bloom, Sara Brenneis, William P. Childers, Uri Cohen, Isabel Durn, Eko, Laszlo Erdelyi, Marcela Garca, Matthew Glassman, Erica Gonzlez, Roberto Gonzlez Echevarra, Jorge E. C. Gracia, Edith Grossman, Ivn Jaksi , Steven G. Kellman, Stacy Klein, Tom Lathrop, Jeffrey Lawrence, Chris Lovett, Luis Loya, Victoria Maillo, James Maraniss, Roberto Mrquez, Juan Carlos Marset, Juan Fernando Merino, Rogelio Miana, Mara Negroni, Glenda Nieto, Eliezer Nowodworski, Maibe Ponet, Burton Raffel, Nieves Romero-Daz, David G. Roskies, Elda Rotor, Nina Scott, Steve Sheinkin, Earl Shorris, Ilene Smith, Gonzalo Sobejano, Neal Sokol, Patricio Tapia, Peter Temes, Carlos Uriona, Julio Vlez-Sainz, Juan Villoro, David Ward, Aline White, Kurt Wildermuth, Karen Winkler, Martn Felipe Yriart, Pablo Zinger, and Ral Zurita.

, Steven G. Kellman, Stacy Klein, Tom Lathrop, Jeffrey Lawrence, Chris Lovett, Luis Loya, Victoria Maillo, James Maraniss, Roberto Mrquez, Juan Carlos Marset, Juan Fernando Merino, Rogelio Miana, Mara Negroni, Glenda Nieto, Eliezer Nowodworski, Maibe Ponet, Burton Raffel, Nieves Romero-Daz, David G. Roskies, Elda Rotor, Nina Scott, Steve Sheinkin, Earl Shorris, Ilene Smith, Gonzalo Sobejano, Neal Sokol, Patricio Tapia, Peter Temes, Carlos Uriona, Julio Vlez-Sainz, Juan Villoro, David Ward, Aline White, Kurt Wildermuth, Karen Winkler, Martn Felipe Yriart, Pablo Zinger, and Ral Zurita.

Finally, the extraordinary people of Restless BooksAnnette Hochstein, Joshua Ellison, Michael Berk, Nathan Rostron, Jack Saul, Brinda Ayer, Alex Sarrigeorgiou, and Renata Limnallowed me the opportunity to delve into the topic with their full support. I am in their debt.

W hen Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra died in Madrid at the age of sixty-eight on the evening of April 22, 1616, and his remains were buried in an unmarked grave at the Convent of the Barefoot Trinitarians (Trinitarias Descalzas), fewnot even Cervantes himself, in spite of his reputation as the Prince of Witspredicted that his work would have a secure place on the bookshelf of classics. It is true that the First Part of his magnum opus, El ingenioso hidalgo don Quijote de la Manchain English The Ingenious Hidalgo Don Quixote of la Manchahad achieved a succs destime that reached far and wide. But in early-seventeenth-century Spain, the novel wasnt considered as prestigious as other literary genres, such as the comedia, a favorite of theater-goers, or the sonnet, a poetic form that elicited obsessive devotion among lovers of prosody.

This novel in particular was a spoof; that is, it was not considered a serious work of artistic expression. Plus, Cervantes was known as a playwright of modest talent, not as celebrated as Flix Arturo Lope de Vega y Carpio, who was known as the Phoenix of Wits and author of nearly eighteen hundred comedias and three thousand sonnets, few of which survive today. Nor did Cervantess sonnets or other poetic exercises, also seen as tame in comparison to those by such figures as Francisco de Quevedo and Luis de Gngora, grant him a secure place among his literary peers. Though today the Spanish government offers the annual Premio Cervantes to honor the lifetime achievement of an outstanding writer in the Spanish language, an award that frequently goes to figures whose work coheres with the intellectual status quo, it is unlikely that Cervantes himself would have been the recipient of such an award. It was Lope de Vega, in fact, who, commenting on the writers on whose oeuvre readers needed to keep an eye on the upcoming year (1604, though the date is debatable), mercilessly stated, None is as bad as Cervantes.

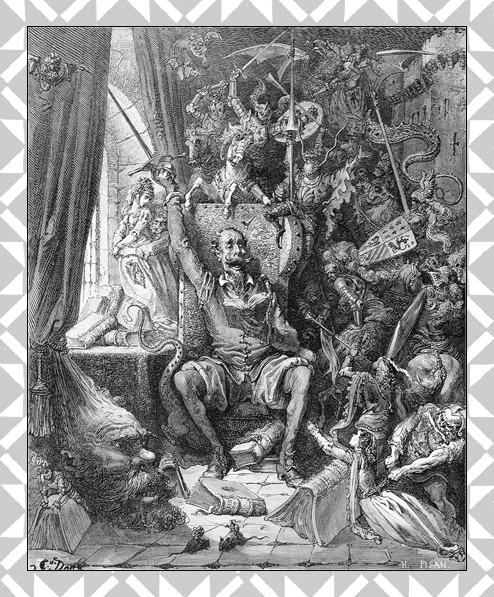

The overall plot of El Quijote is rather easy to summarize, although any summary of it inevitably feels reductive, even stilted. A fiftyish hidalgo by the name of Alonso Quijano (also known as Quijana, Quijada, and Quesada), living in a hacienda in an unknown place in the region of La Mancha in central Spain, has been spending his days reading novels of chivalry, marvel-filled cycles of narratives, extremely popular among aristocratic readers, written in prose or verse and based on fantastic legends that featured a masculine hero, a knight-errant who embarks on a quest while usually declaring Platonic love for his dame. The word hidalgo comes from fidalgo. According to lore, it means hijo de algo, child of someone. In truth, it refers to a member of the lower nobility. It might also refer to someone whose ancestry was defined by purity of blood, that is, one who came from a family of old Christians.

In Spain at the time, there were different kinds of hidalgos, as listed in the Diccionario de la Real Academia Espaola (DRAE), including the hidalgo de ejecutoria, someone whose blood lineage makes him such, and the hidalgo de privilegio, a person whose position is acquired through money or privilege. The novels narrator doesnt offer any further detail. The reader is simply told that the protagonist is a hidalgo who lives with his niece, who is under twenty; a female housekeeper, who is past forty; and a lad who does the field work. That this hidalgo is on good terms with the towns priest and barber. And that he doesnt attend to the affairs of his hacienda because he spends all his time reading. Indeed, such is his habit that, in John Ormsbys English translation (hereafter used, unless stated otherwise), published in London in 1885, we are told:

Next page

, Steven G. Kellman, Stacy Klein, Tom Lathrop, Jeffrey Lawrence, Chris Lovett, Luis Loya, Victoria Maillo, James Maraniss, Roberto Mrquez, Juan Carlos Marset, Juan Fernando Merino, Rogelio Miana, Mara Negroni, Glenda Nieto, Eliezer Nowodworski, Maibe Ponet, Burton Raffel, Nieves Romero-Daz, David G. Roskies, Elda Rotor, Nina Scott, Steve Sheinkin, Earl Shorris, Ilene Smith, Gonzalo Sobejano, Neal Sokol, Patricio Tapia, Peter Temes, Carlos Uriona, Julio Vlez-Sainz, Juan Villoro, David Ward, Aline White, Kurt Wildermuth, Karen Winkler, Martn Felipe Yriart, Pablo Zinger, and Ral Zurita.

, Steven G. Kellman, Stacy Klein, Tom Lathrop, Jeffrey Lawrence, Chris Lovett, Luis Loya, Victoria Maillo, James Maraniss, Roberto Mrquez, Juan Carlos Marset, Juan Fernando Merino, Rogelio Miana, Mara Negroni, Glenda Nieto, Eliezer Nowodworski, Maibe Ponet, Burton Raffel, Nieves Romero-Daz, David G. Roskies, Elda Rotor, Nina Scott, Steve Sheinkin, Earl Shorris, Ilene Smith, Gonzalo Sobejano, Neal Sokol, Patricio Tapia, Peter Temes, Carlos Uriona, Julio Vlez-Sainz, Juan Villoro, David Ward, Aline White, Kurt Wildermuth, Karen Winkler, Martn Felipe Yriart, Pablo Zinger, and Ral Zurita.