Catherine M. Conaghan, Editor

Montaigne, Of Cannibals (trans. John Florio, 1603)

1

THE PULL

I was past fifty when the pull made itself apparent.

I had left Mexico, my place of birth, decades earlier and now lived a comfortable life elsewhere. Yet I had kept close ties with my family throughout the years. Then an unexpected rift took place among them, with immediate and far-reaching consequences. One consequence was that I suddenly felt uprooted.

This sense manifested itself in a bizarre, prophetic dream. In it I was walking in Colonia Copilco, the neighborhood in Mexico City where I grew up and to which I hadnt returned for ages. In the dream I looked for my old house, but block after block I couldnt find it. I became agitated by its absence. After a while, I finally stumbled upon it. A mysterious man was waiting at the door. He saw me but didnt make any gesture.

He was in his mid-sixties, disheveled. He wore thick glasses, a long, unkempt, salt-and-pepper beard, and a small hat that looked disproportionally large on his round bloated head. Under the hat I could see a yarmulke. There was something feminine about his lips. I had the vague feeling of having met the mysterious man before but I couldnt remember where. I was sure he wasnt Mexican. I approached him hesitantly. For some reason I dont understand, I decided to address him in French.

Monsieur, voici ma maison. I explained that I had come from far away and needed to get into the house. He didnt budge. For a moment I thought he was mute.

When I was growing up, there was a small park around the corner from my childhood home. I walked toward it. It had changed tremendously. In fact, in the dream it was now an amusement park. There was a carousel, a Ferris Wheel, bumper cars, a rollercoaster, and some other attractions.

I found the ticket booth. An old lady was inside. I handed her money and told her I wanted to purchase a ticket.

Pa qu? She spoke a working-class Mexican Spanish. What for?

I told her the ticket was to go to my old house. I hadnt seen it for a long time. I feared I was forgetting what rooms looked like, what it felt to be inside, how the morning light projected itself against the house walls.

She smiled and handed me a ticket and some coins. I walked back to my house. The mysterious man was still there. I showed him the ticket.

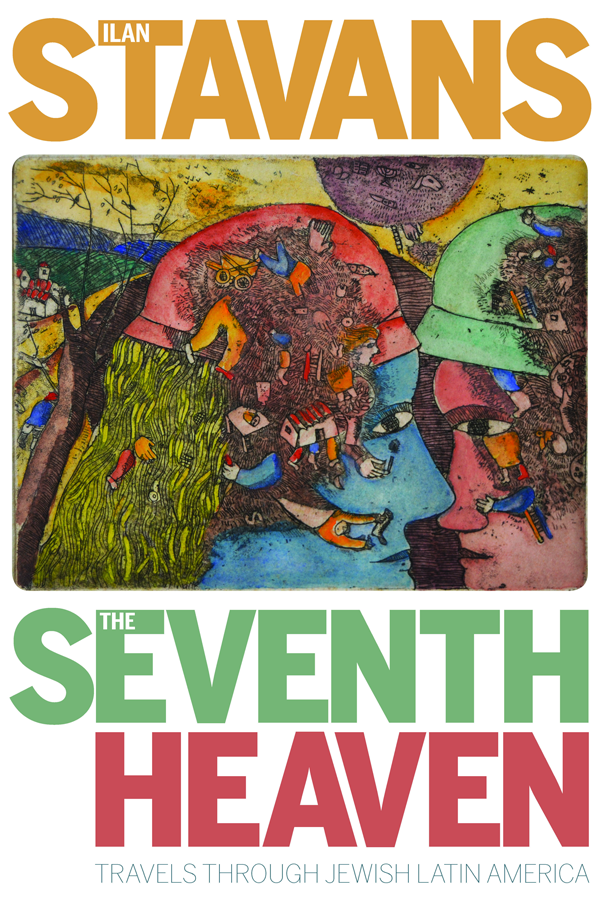

He looked bewildered and laughed euphorically. Bienvenue au septime ciel, he announced. Welcome to the seventh heaven.

At this point, I woke up...

I seldom remember my dreams. In fact, every morning as I wake up I go through a certain motion. Eyes still closed, I become aware Im about to lose grasp of the images in the dream and futilely attempt to freeze them. I open my eyes and close them, in quick succession, but it is pointless. Throughout the day I also foolishly look for these images, again to no avail.

This particular dream was different. It was stamped into my consciousness, bouncing spiritedly from one corner to another. Interpreting it became a sport of sorts. I looked for photos of the faade of my Copilco house, the interior, the third-floor deck, a tree in the front yard. And I tried to retrieve the identity of the mysterious man. One thing became clear to me. The fact that I couldnt just reenter my childhood house meant I was now a stranger to it. More than a stranger, a tourist, because to get in I needed to pay the price of admission. In other words, my house was mine no more.

Plus, there was the expression au septime ciel. I had heard it at a dinner table just a few days prior, I believe for the first time. I remember being puzzled by it. The guest at the party had used it to refer to a mutual acquaintance whose life was somehow out of focus. He is in seventh heaven...

In any case, the dream became a kind of obsession. I thought about it constantly. Its deeper implications frightened me. It made me feel disconnected from my past.

Something else happened at the time. I had been reading a book originallywritten in Yiddish called The Enemy at His Pleasure. (The original title is Khurbn Galitsye, the destruction of Galicia.) The author was a folklorist called Shloyme Zaynvl Rapoport, who went by the penname of S. Ansky. He is best known for a classic theater piece, The Dybbuk: Between Two Worlds (1920), a haunting play about an exorcism. I have seen the play staged half a dozen times.

The action of the play takes place in 1882, in a shtetl in Miropol, Volhynia. In it there is a girl who is the daughter of a rich Jew. The father makes it difficult for suitors to satisfy his demands for his daughters marriage. At the same time, a yeshiva student is in love with her. But in the fathers eyes he is unworthy. Distraught, the student dies. Soon a match is made for the girl to marry a man who is finally approved by the father, though not before the yeshiva students malicious spirit, known in Jewish folklore as dybbuk, takes possession of her.

Ansky was a socialist as well as a Yiddishist who believed that the soul of people was to be found in their language. He was from Chashniki, Belarus, which at the time was part of the Russian Empire. And he died in Otwock, Poland. In other words, he was from the so-called Pale of Settlement, the territory in the western region of imperial Russia where the Jews were allowed to live between 1791 and 1917.

He was appalled by the miserable conditions in which they lived in the region. Poverty was endemic. Anti-Semitic outburstscalled pogromswere at a premium. This was the age of revolution. It was the age of large-canvas social engineering, of Communism, Anarchism, Nihilism, and other doctrines intent on remapping human interactions. And this was also the time when Jewish philanthropies were committed to relocating enormous masses of people to destinations such as the United States, Palestine, and Argentina.

Around the First World War, struck by a sense of urgency, Ansky headed an ethnographic expedition to towns in Volhynia and Podolia, which covered parts of Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, and Moldova. He took it upon himself to compile a multifaceted narrative (when first released, The Enemy at His Pleasure was in four volumes, the version I read in English being an abridgment) that offered a portraitphysical, psychological, and religiousof a society, the poor Jewish people of the Pale of Settlement as they struggled to make ends meet.

To accomplish this, Ansky and a set of teammates he assembled interviewed hundreds of people with a questionnaire of more than two thousand questions. They recorded five hundred cylinders of music and acquired photographs,manuscripts, and religious paraphernalia. From these he drew natural and supernatural stories, some of them about sheer survival, others about violence, and a few more about angels and demons and golems and goblins. The result, as I once saw it described, was a Brueghel-like canvas of a world on the verge of extinction.