Contents

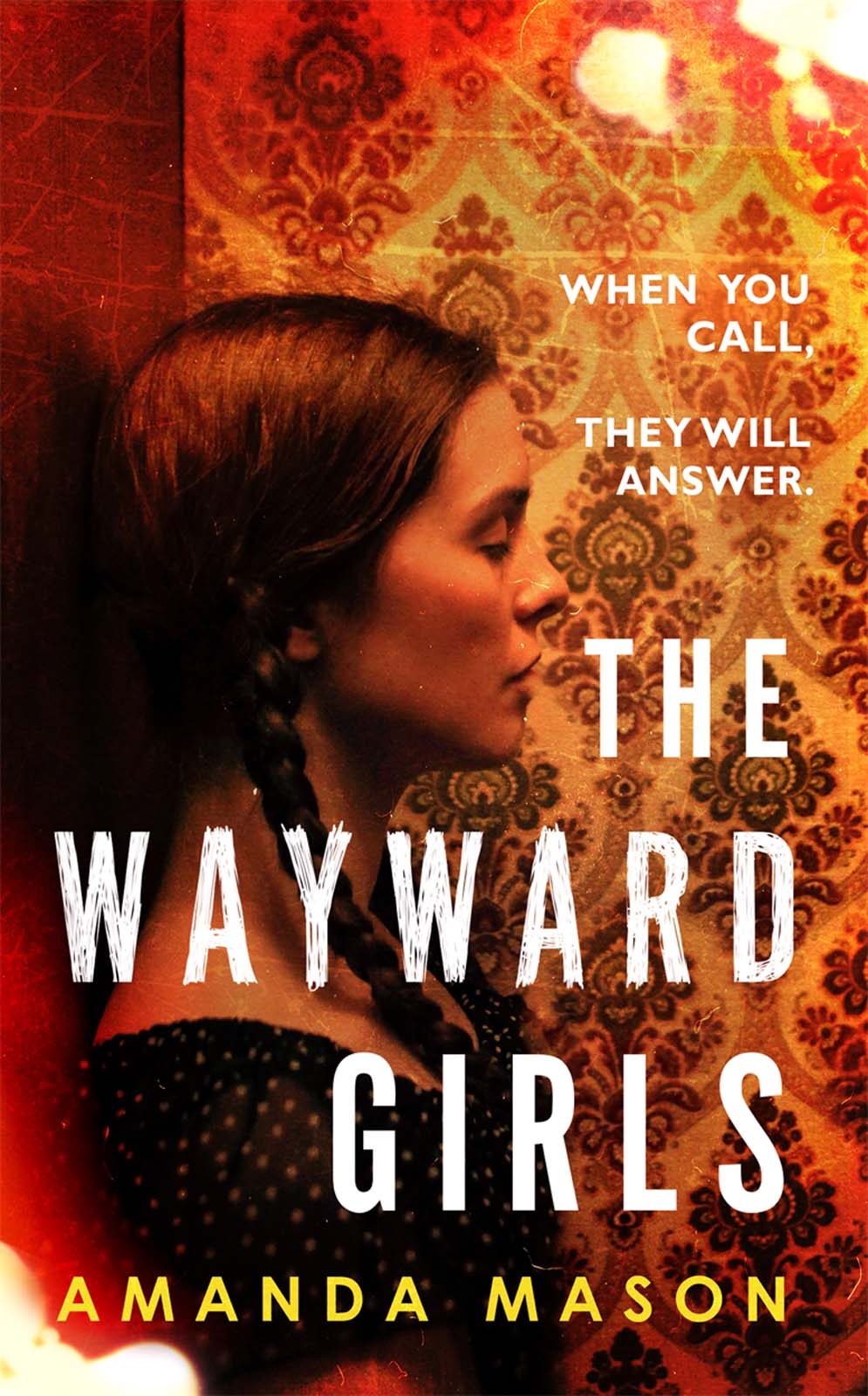

Amanda Mason was born and brought up in Whitby, North Yorks. She studied Theatre at Dartington College of Arts, where she began writing by devising and directing plays. After a few years of earning a very irregular living in lots of odd jobs, including performing in a comedy street magic act, she became a teacher and has worked in the UK, Italy, Spain, and Germany. She now lives in York and has given up teaching for writing. Her short stories have been published in several anthologies. The Wayward Girls is her debut novel and was longlisted for the Deborah Rogers prize.

For Jim Mayer

07.10.46 16.08.16

Stand still. Bee tugged at Loos petticoat, trying to straighten it.

I dont like it, said Loo. The cotton was soft and cool but it smelt funny, as if it had been left out in the rain. It made her skin crawl.

Oh, shut up. Bee stood back, concentrating. Her own petticoat had a frill around the skirt and the top she wore the camisole had lace edging at the neck; she looked different, not pretty exactly, but more grown-up. She stood with her hands on her hips, her head tilted to one side, scowling, her long dark hair flopping into her eyes.

Its too long. Loo kicked at the skirt. I cant walk in it.

Well, well pin it up, then, Bee said, as if her sister was either very small or very stupid. God, Loo, its not stay here, and dont let Cathy see you. She opened the door, then turned back, her expression stern. Dont move a muscle, she said, before ducking out of the room and running lightly across the landing, disappearing into their parents bedroom.

They had found the box in the pantry, shoved out of sight under the shelves, and had brought it up to their room while their mother, Cathy, was busy in the garden with everyone else. The cardboard was speckled with damp and there was bold blue print running along one side: GOLDEN WONDER . It was old, but not as old as the clothes theyd found inside.

Cathy wouldnt be pleased. She might even take it away; it wasnt really theirs, after all. She might want the clothes for that was all the box held, petticoats and nightgowns and camisoles, a lot of them, too much for one person, surely she might insist they hand them over to their rightful owner, whoever that might be.

Bee was taking ages. Loo ran her hands across the fabric, trying to smooth out the deep creases that criss-crossed the skirt, some of them a faint brown. The fabric was paper-thin and she wondered if it might tear if she pulled it hard enough. What Bee would say if she did.

It was stuffy in their bedroom. She went to the window and, pushing it as far open as she could, she leant out.

They were still there, all the grown-ups and Flor and the baby, sitting on the grass under the apple tree at the far end of the garden, not doing much, any of them; it was too hot.

Simon was sitting next to Issy, and they were talking to each other. Loo wondered what they might be saying. Issy raised her hand to her face to shade her eyes whenever she spoke and Simon leant in close, as if he was whispering secrets in her ear.

Odd words drifted up to the open window, but nothing that made much sense. Issy laughed once or twice and Loo suddenly wished they would look up, one of them, see her, smile. She leant further out, bracing her hands on the window ledge, on the warm, blistered paint, letting the sun bake her arms.

There was a shift in the air as the door swung open. She felt Bee cross the room and stand behind her, looking at the same view, at Simon. She leant in closer. Her breath was stale, her hip nudged Loo, one arm draping around her shoulders and her weight settling on her, skin on skin, edging Loo off balance. It was too much, too hot; besides, they never hugged. Loo tried to pull away and felt an answering pressure across her shoulders as her sister refused to budge, her fingers digging into the soft skin at the top of Loos arm.

I told you not to move. Loo jumped back from the window, startled. Bee was standing by the door, well out of reach, her mothers pin cushion in one hand, needle, thread and scissors in the other. Loo felt dizzy, the room seemed to shimmer briefly, then everything came back into focus, sharp, solid. Bee was giving her a funny look.

Youre bloody useless, you are. Bee dragged her in front of the mirror again. She grabbed the waistband of the skirt and pinched it, pulling it tight, pinning it into place before she knelt and began to work on the hem. You can sew it yourself, though, she said. You neednt think Im going to do it. She worked quickly, so quickly Loo was sure the hem would turn out lopsided.

Bee?

What?

Will Joe come back soon?

Joe, not Dad. Cathy, not Mum. Loo wasnt sure when theyd started using their parents proper names, or even whose idea it had been in the first place, but they all did it now, except for Anto, who was too little to say anything.

Bee stopped what she was doing and looked up. She didnt look angry, exactly, but still Loo wished she hadnt said anything. Suppose so, she said, turning her attention back to the hem. She sounded as if she didnt care at all, but it was hard to tell. Bee was such a bloody liar, thats what Joe used to say whenever he caught her out. He thought it was funny, most of the time, and Loo had often wondered if she did it for that exact reason, to make him laugh.

Bee

Shut up, Loo.

There was no point in asking anything else.

There, Bee said as she got to her feet. Thats better.

Bees outfit didnt need altering. Her skirt didnt sag down onto the floor, and the camisole she wore was a little bit too tight, if anything. As if the girl they once belonged to fitted between the two of them, between Bee and Loo.

She should say something, about the window, about the

It looks stupid with this. Loo plucked at her T-shirt, which had once been bright blue, and she could see that Bee was torn. I dont mind, she said, you can have it all.

And she didnt mind the clothes in the box, she didnt like them. She tugged at the skirt again. It felt wrong.

Well, that wont work, will it? said Bee. We have to match. She rifled through the clothes on her bed, pulling out a little vest, greyish white and studded with tiny bone buttons. Here. Try this.

Loo didnt move.

Bloody hell, Loo. Youre not shy, are you? Bee chucked the vest at her. I wont look, she said, turning back to her bed and making a show of sorting through the remaining clothes.

Loo turned her back on her sister and the mirror too, peeling off the T-shirt and letting it fall to the floor, shaking out the camisole and pulling it over her head as quickly as she could, her skin puckering despite the heat as the musty cloth settled into place.

It was too big. She didnt need to look in the mirror to see that, but she looked anyway. It was almost comical, the way the top sort of slithered off her shoulder, as if she had begun to shrink, leaving the clothes behind. She might have laughed, if it hadnt felt so

Bee grabbed her and swung her round. Well have to fix this too, she said, pulling the camisole back into place and digging the pins through the double layers of cotton.

Ow. Loo flinched as Bee scraped a pin across her collar bone.

Oh, give over. I didnt hurt you. Bee swung her around again and began to gather the fabric at Loos back. Now, stay still.

Loo did as she was told. It was always easier to do as shed been told, in the end. Anyway, the sooner Bee finished, the sooner she could have her own clothes back.

![Amanda Mason [Amanda Mason] The Wayward Girls](/uploads/posts/book/140005/thumbs/amanda-mason-amanda-mason-the-wayward-girls.jpg)