Table of Contents

Contents

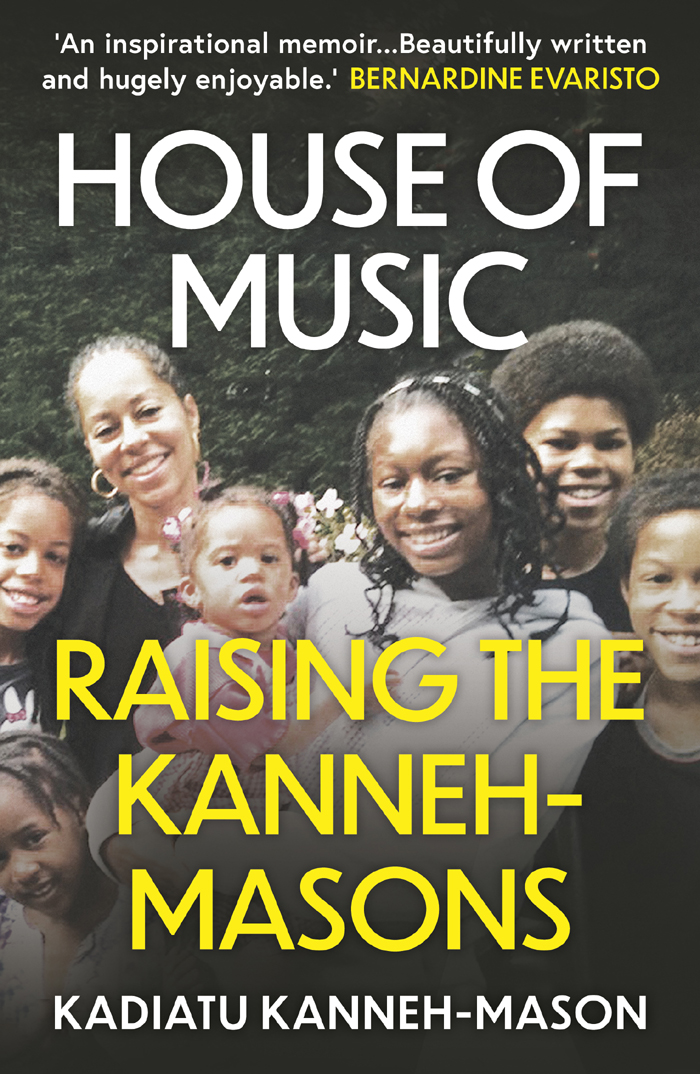

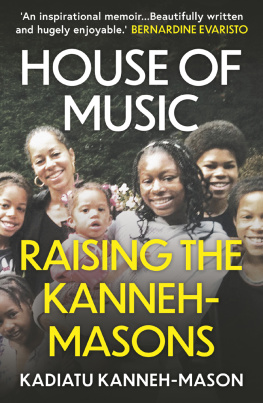

For my mother, Megan Kanneh, and for my father, A.B. Kanneh. For my sister, Isata, and my brothers, Steven and James. Also for Stuart, and of course Isata, Braimah, Sheku, Konya, Jeneba, Aminata and Mariatu.

Prologue

Into the World

I T WAS BRIGHT and warm, with nowhere to hide. I swallowed the impulse to cower inside, willing the hours to pass. We were at the precipice and there was no turning back. The 15th May 2016 was a day that the whole family had worked towards for longer than we could remember. All of us were implicated in the collective drama, reaching its final act on a day stark with light. I wanted to pull away from the glare and tuck my children in behind me. I wanted to wear a black jumper and creep inside, somewhere out of view. My third child, Sheku, had worked unrelentingly for this moment. We as a family had listened to him, watched him play, commented on every note, every expression, every intonation of each bar, each piece. We watched him become a cellist, guided and honed by his teacher, and helped him to grow into this boy who had to fill a London concert hall with sound and meaning.

Today was the Final of BBC Young Musician. At sixteen, Sheku had gone through nine months of gruelling work to make his way through each round of the competition. Now he had turned seventeen. I thought about how and why we had started on this long road, with all the demands of daily practice and hours of unremitting focus. I remembered the six-year-old boy with the quarter-size cello and how he transformed when he touched it. The wild, active, naughty boy with a love of gymnastics, football and secret jokes with his brother would become still and almost reverential, listening to the sound that came from bow and string and hearing nothing else. The sudden concentration on his face as he touched the cello, the flow of feeling that came from boy and instrument, seemed to change both and to create something entirely new. We had no choice.

We arrived early. Sheku was already backstage at the Barbican, having stayed nearby and rehearsed for a few days. He had shared a hotel room with his Dad, Stuart, the perfect companion. Stuart was utterly involved, intensely committed, but he was also the one who could give Sheku those relaxed evenings, watching football on the TV and talking sport. Had I been Shekus companion, I would have been a wound spring and comprehensively got on his nerves.

We all entered the cool building and there, coming out of the backstage door, was Sheku. I paused, knowing that the full wave of my unruly emotions had no place here. Braimah, his brother, went straight to him and I was grateful for that easy, big-brother companionship. My role was different, and I needed to stand back and let Sheku breathe. But he was too compassionate for that and came for a sympathetic hug. I burst into tears.

I wiped my face as Sheku disappeared backstage, aching with the effort to let him go, and we all entered the main foyer. It was crammed, loud with speculation and curiosity.

The BBC Young Musician Final is an event heady with precedent. Many major British classical musicians have emerged from past Finals, and the fact that it has been televised since 1978 has pushed it to almost mythic status. My son had made it to this legendary Final, and here we all were Shekus six siblings, my husband and myself unimaginably entering the Barbican for the last concerto round.

There had been an article in The Times the day before by Julian Lloyd Webber, which finally asked the question that the media had not dared name. It brought to the fore what everyone had been thinking. How did a young Black boy from a state-funded school in Nottingham get to this prestigious Final? And why was he the only one ever?

Suddenly, we were surrounded by representatives from Trinity School, not only Shekus music teachers but also his head teacher, former head teacher and other subject teachers, all coming as a surprise to support their pupil. I was overwhelmed by this swell of belief and celebration. They had travelled all the way from Nottingham to London to gather around Sheku and cheer him on. Then Shekus grandmother, aunties and cousin arrived. Shekus cello teacher and some of the childrens instrument teachers also came, as well as a host of friends. The luthier who had made the cello Sheku played before and during the earlier rounds was there with his wife, and other parents of musical children. This sense of companionship made me melt with gratitude.

The crowd started entering the concert hall, impressive in its width with tiered theatrical semi-circular seating and a long stage ready with the orchestras chairs. Most of us had never before set foot in a major London concert hall. Now, we were taking our seats to see Sheku play Shostakovichs Cello Concerto No. 1 with the BBC Symphony Orchestra on the most important day of his life.

But this was a competition. Two other soloists were to take their turn on the stage, and they were formidable competitors. Ben Goldscheider would play the French horn and Jess Gillam the saxophone. All three were friends, and all bright with concentration.

We watched the television cameras around the hall and close to the stage with mounting anxiety as the hall filled to capacity. I looked at the faces of the six of my children who were in the audience. Mariatu, aged six, was sitting bolt upright with her braids falling like corkscrews around her face. She was wearing her favourite going-out dress and couldnt wait to see Sheku walk out with his cello. Her quarter-size cello was waiting at home, wrapped up in its dusty canvas case. It had been Shekus and Jenebas first cello, but Mariatu had not yet started playing it. For now, she was continuing with violin, but turning her attention all the time to the cello. Whenever Sheku played, Mariatu would move closer and sit on the floor in front of him, transfixed by the sound.

Aminata, aged ten, was sitting nervously with her big dark eyes darting round the crowds, not missing a thing. Konya and Jeneba sat next to each other, bound by anticipation. I looked along all their black-braided heads to Braimah, who was also thinking only of his brother, and Isata sitting further along with her fellow Royal Academy of Music students. Stuart, my husband, fidgeted beside me while I sat rigid.

There is something mesmerising when a moment long dreamed of begins to unfold. We sat, our whole family, in the hushed shadows of the audience, all faces turned to my son on stage, in the centre of a fierce and magical concentration. I knew every note of the concerto. Every phrase of music had been practised, discussed at length, experimented with for months before. There had been in-depth lessons at the Junior Royal Academy. Sheku had worked carefully through the score with the composition teacher. Hed had run-in performances and consultations. Braimah had sat with Sheku for hours, focusing on the bowing, the tone, the meaning of each note and passage.

There was nothing rushed about this moment, and yet it was intensely spontaneous. Something new and unrepeatable happens in live performance and Sheku can create a new and bold alchemy every time he walks on stage. Even though I had heard every note before, I found the performance a revelation.

![Amanda Mason [Amanda Mason] - The Wayward Girls](/uploads/posts/book/140005/thumbs/amanda-mason-amanda-mason-the-wayward-girls.jpg)