Table of Contents

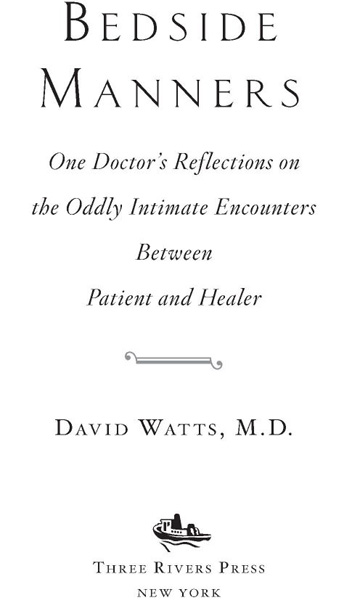

For my patients...... and for Joan

You can observe a lot by watching.

YOGI BERRA

Praise for BEDSIDE MANNERS

Dr. Watts is a healer in the truest sense. Reading these stories will change lives. They just might change your life, too.

Melanie Austin, M.D., in Cell 2 Soul

Undeniably compelling.

Kirkus Reviews

Both empathetic and practical, Watts relates encounters that have informed his ability to understand, diagnose, and treat sickness.... All of the incidents related here, whether sad, frustrating, or inconclusive, are unfailingly compelling.

Publishers Weekly

David Watts is a gifted storyteller with a sense of the poetic, macabre, ironic, and surreal. He combines eloquence, erudition, and an ear for the gritty vernacular of the examining room and ERa thoroughly satisfying read.

Leonard Shlain, author of The Alphabet Versus the Goddess and Sex, Time and Power

These encounters with his patients by a wise, kind doctor are finely wrought in language that is always clear and compassionate. They are a welcome addition to the growing body of literature from the experience of medicine.

Richard Selzer, surgeon and author of The Whistlers Room

A moving, eloquent insight into what a sensitive physician feels and thinks encountering a variety of patients and problems. A must-read for doctors and patients alike.

Paul Ekman, Ph.D., author of Emotions Revealed

PREFACE

Can you tell me a growing-up story?

The request came from my son, Duston, as I was tucking him into bed. I am familiar with this request. He makes it mostly when he is troubled. Maybe another child has said something mean to him. Maybe hes having to deal with the unthinkable idea of war or capital punishment. Growing up is not easy or fair.

Yet what puts things in place for him and makes him feel better is stories, especially about times past. Instinctively he knows that something is to be found there that will teach or reassure or lull. And I realize that by this ritual he will come to know my relatives, living and deadto know them by how they come alive and speak and drive cars and take apart tractors for him in the late evenings.

I never intended to be a storyteller. I came to writing because I was looking for something. I was in a difficult transition and I wanted to find a way to say what was going on inside me or maybe just to find out what was there. I was drawn first to poetry because of its traditional subjects: love, loss, longing... the complex and rich and sometimes painful interactions of the family... There was stuff there to work with.

As I wrote, I became aware of this niggling little tap, tap, tapping on my shoulder. And a voice that said, Shouldnt you write on the subject you know the most about?

I didnt want to write about my work. But I had to admit that medicine had a rich and beautiful language, and there was a music to the words one could get lost in. And there exists within the doctor-patient relationship this rarest of conditions, which gives the people involved permission to engage in instant, profound human interaction. Its like stepping suddenly into a clearing. Even so, writing about medicine was for someone else.

Well, I finally gave in. My first efforts at writing about the doctor-patient relationship sounded more like articles for the New England Journal of Medicine than anything remotely related to art. The cold, distancing language of medicine had crept in and locked out feeling. It was not until I became ruthlessly honest in my treatment of my subject and, by the same token, of myself as a doctor that the language of academics disappeared and the music began to return.

The real turning point came when a young violinist with cancer became my patient. Her struggle and her bright spirit were so inspiring that I just had to find where that passion was coming from. Writing about her taught me how to find what lay underneath. Writing about her allowed me to be deeply moved by other patients with other stories.

Life has a certain irony. My grandfather says that sometimes you just have to go where the horse wants you to go. My horse apparently wanted prose, and wanted it to speak of the struggles of doctors and patients.

Then another surprise: The subjects I was attracted to, the ones that had brought me to poetry in the first place, were to be found quite at home within the heart of medicine. And perhaps to greater effect, for here the tension between the professional and the personal, the locus of these strong emotions within the hard reality of medicine, gave them a certain fresh architecture, a scaffolding to hold on to. And as I learned more clearly from writing about it, the office visit, with its urgency and compression, its precise language and powerful emotions, is itself a poetry.

The stories in this book are true. What I wanted most to celebrate by writing them were the wonderful and inspiring qualities of my patients: their courage, their inventiveness, their quirkiness, even the admirable way they are sometimes irascible and defiant. There is wisdom in the particulars of these characters. Like reflections on the surface of a complex gemstone, these sparkles of personality are what makes the medical experience so interesting, so human, and so impossible to predict.

Something happens when we sit down face-to-face in the spirit of mutual trust and talk about vital issues of health and mortality. Lives open up. We see things we had passed by day after day and never recognized about ourselves. Moreover, this information opens out onto balconies of change, sometimes radical ones. Ive seen patients go out and divorce their spouses or change their careers based upon what they learn about themselves. Much of the mysterious action of the human spirit comes forth when we finally relinquish our hiding places. Thats what this book is aboutwhat we do about our lives when confronted with mortality.

There are situations and syndromes here that, to my knowledge, have not been described beforeor at least I had not known about such things: the man who had to stay awake to stave off his demons during endoscopy, the woman who used poetry to get through a frightening procedure, the doctor who made his living saying yes to insurance companies, the doctor who finally learned how to find value caring for a thankless patient...

It turns out, as I wrote deeper and deeper into my subject I revealed more and more about myself. That, I guess, is what literature does. Makes us set aside inhibitions. Makes us find a pathway to the interior. I write the story, the story writes me.

Some of what I wrote was too painful or specific to include here. The doctor-patient relationship is a sacred and fragile covenant. Patients have a right to their privacy. When writing about my patients I have always asked their permission and with rare exception they would say something like, Oh, thats wonderful. Please do. I think they were genuinely honored to be so recognized. Some names I could not remember. Some people I could not find. But I always tried to disguise my subjects well enough so as to honor the unspoken agreement. Some may recognize themselves. Some may only think they do. The circumstance of literature is specific to us all.

Sometimes, writing these stories late at night, I have become weary with pleasure. Sometimes, reading them again brings the pleasure back. There is a wisdom in stories that goes beyond the circumstance of their creation, and there is a comforting sense of continuation and resilience. Perhaps that is what my son has found there. Gratitude, then, to those who have given us their stories, those who taught me what I now know, and made me a better doctor because of it.

Next page