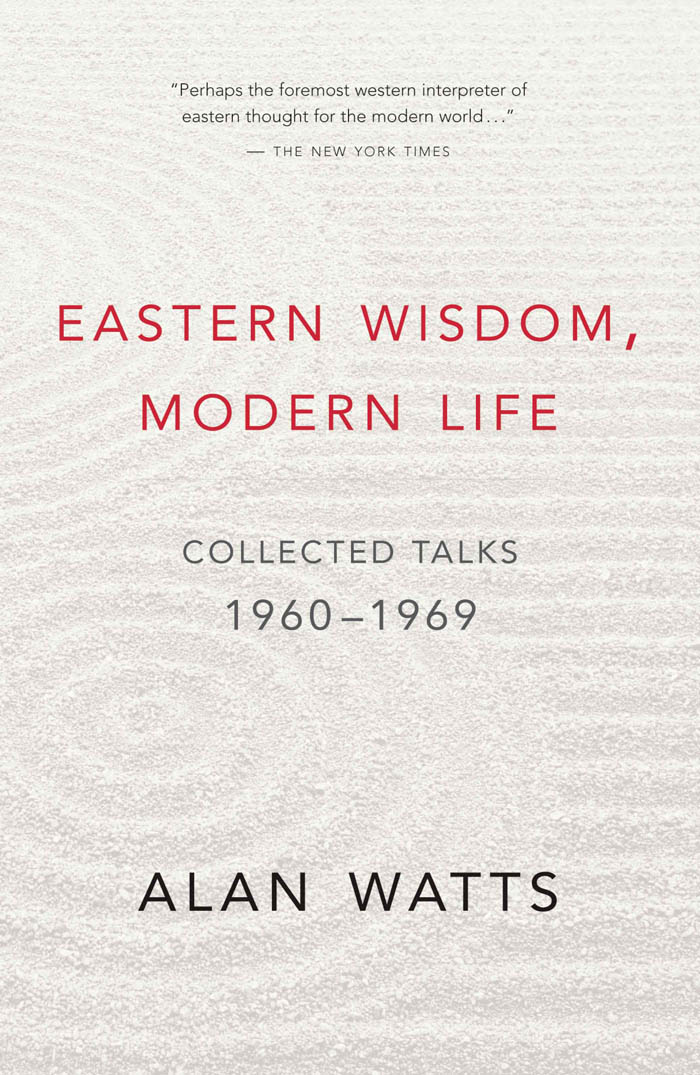

Watts - Eastern Wisdom, Modern Life: Collected Talks 1960-1969

Here you can read online Watts - Eastern Wisdom, Modern Life: Collected Talks 1960-1969 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Novato, year: 2006, publisher: New World Library, genre: Religion. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

Eastern Wisdom, Modern Life: Collected Talks 1960-1969: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Eastern Wisdom, Modern Life: Collected Talks 1960-1969" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Watts: author's other books

Who wrote Eastern Wisdom, Modern Life: Collected Talks 1960-1969? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Eastern Wisdom, Modern Life: Collected Talks 1960-1969 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Eastern Wisdom, Modern Life: Collected Talks 1960-1969" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

MODERN LIFE

MODERN LIFE

1960 1969

Copyright 1994, 1995, 1998, and 2006 by Alan Watts

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, or other without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Chapters 4, 8, 10, 13, and 16 appeared earlier in the book The Culture of Counter-Culture, copyright 1998. Chapters 5, 7, 14, and 15 appeared earlier in the book Myth and Religion, copyright 1995. Chapter 12 first appeared in the book Talking Zen, copyright 1994.

Interior design by Tona Pearce Myers

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Watts, Alan, 1915 1973.

Eastern wisdom, modern life : collected talks 1960 1969 / Alan Watts.

1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN-13: 978-1-57731-180-5 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-57731-180-9 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Asia Religion. 2. Philosophy, Asian. I. Title.

BL1055.W377 2006

294.3 dc22

2006014342

First printing, October 2006

ISBN-10: 1-57731-180-9

ISBN-13: 978-1-57731-180-5

Printed in Canada on acid-free, partially recycled paper

A proud member of the Green Press Initiative

A proud member of the Green Press Initiative

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

E ASTERN W ISDOM, M ODERN L IFE draws upon works from a pivotal decade in the life and works of Alan Watts, a time in which he pioneered ideas and ways of knowing that helped shape the cultural landscape of the 1960s and beyond. A foremost interpreter of Far Eastern wisdom for the Western world, he explored the frontiers of human knowledge, a place where perception and inquiry become the yin and yang of the essential questions Who Am I? What is the meaning of life? and Why are we here?

A native of England, Alan Watts attended the Kings School near Canterbury Cathedral, and at the age of fourteen he became fascinated with the philosophies of the Far East. By sixteen he regularly attended the Buddhist Lodge in London, where he met Zen scholars Christmas Humphries and D. T. Suzuki. As a speaker and contributor to the Lodges journal, The Middle Way, he wrote a series of philosophical commentaries and published his first book on Eastern thought, The Spirit of Zen, at age twenty-one.

In the late thirties he moved to New York, and a few years later he became an Episcopalian priest. In 1942 he moved to Illinois and spent the wartime years as chaplain at Northwestern University.

Then, in 1950, he left the Church, and his life took a turn away from organized religion back toward Eastern ways and expanding horizons. After meeting author and mythologist Joseph Campbell and composer John Cage in New York he headed to California and began teaching at the American Academy of Asian Studies in San Francisco. There his popular lectures spilled over into coffeehouse talks and appearances with the well-known beat writers Gary Snyder, Jack Kerouac, and Allen Ginsberg. In late 1953 he began what would become the longest running series of Sunday morning public radio talks, which continue to this day with programs from the Alan Watts tape archives. In 1957 he published the bestselling The Way of Zen, beginning a prolific ten-year period in which he wrote Nature, Man and Woman; Beat Zen, Square Zen and Zen; This Is It; Psychotherapy East and West; The Two Hands of God; The Joyous Cosmology; and The Book: On the Taboo against Knowing Who You Are.

By 1960 Wattss radio series Way Beyond the West on Berkeleys KPFA had an avid following on the West Coast, and NET television began national broadcasts of the series Eastern Wisdom in Modern Life. The first season, recorded in the studios of KQED, a San Francisco television station, focused on the relevance of Buddhism, and the second, on Zen and the arts. The chapters in part 1 of this book were adapted from the opening programs in the second season, including Buddha and Buddhism, Mahayana Buddhism, and The Discipline of Zen. They were intended to introduce the Buddhist approach to the psychology of religion.

The chapters in part 2 were drawn from some of Wattss engaging public lectures between 1963 and 1965. They include talks he gave at major universities, on Mysticism and Morality, The Images of Man, The Relevance of Oriental Philosophy, and Religion and Sexuality. In these talks he delivered powerful and pointed critiques of the role of Western religion in modern society and proposed a broader view of the divine to receptive young audiences.

Part 3 is based on seminars and lectures recorded between 1965 and 1967 and includes deeply considered perspectives on From Time to Eternity, leading into the Philosophy of Nature, as he called the philosophy of the Tao, or Way. In Taoist Ways and Swimming Headless, one finds a profound appreciation for the course and current of nature, including our own nature as human beings. Part 3 ends with Zen Bones, a stirring talk on the Zen methods of intellectual liberation and an introduction to the realm of mystical vision.

The fourth and final part picks up where part 3 leaves off, with Divine Alchemy, a 1968 talk on the use of sacraments specifically and mystical experience generally. Then, in the final three talks, Democracy in Heaven, Not What Should Be, but What Is! and What Is Reality? Watts raises and answers the question Where do we go from here? providing suggestions for living with the Tao in contemporary society.

Although the following selections are only a handful of the many talks Alan Watts gave in the sixties, they have been selected to represent the whole, and to present the highlights of a career that reflected the philosophical openness of the sixties and paved the way for the flood of interest in the traditions of the Far East that followed.

Mark Watts

I N THIS SERIES OF ARTICLES on Eastern wisdom and modern life, Im going to be exploring Buddhism and Zen, Zen being a particular form of Buddhism which flourishes in Japan and China.

You may wonder why I am particularly interested in investigating Buddhism as distinct from other forms of Asian philosophy and religion. The reason is that Buddhism is a method of liberation which has emerged as a way of life in Asia, but which is not so closely tied to the different cultures of Asia as such other philosophies or religions as Hinduism or Confucianism or Shinto. Shinto, for example, is the national cult of Japan, and it would be impossible, really, for Shinto to migrate to any other people than the Japanese. In the same way, Confucianism is intimately bound up with Chinese culture. And also Hinduism is tied to the particular culture and social order of India. Although it began in India, Buddhism has migrated to all parts of Asia and has adapted itself to all kinds of different cultures. And so, in this way you might say Buddhism is an intercultural or even international way of life, and therefore of all the forms of Asian philosophy it is probably of most interest to the West.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Eastern Wisdom, Modern Life: Collected Talks 1960-1969»

Look at similar books to Eastern Wisdom, Modern Life: Collected Talks 1960-1969. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Eastern Wisdom, Modern Life: Collected Talks 1960-1969 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.