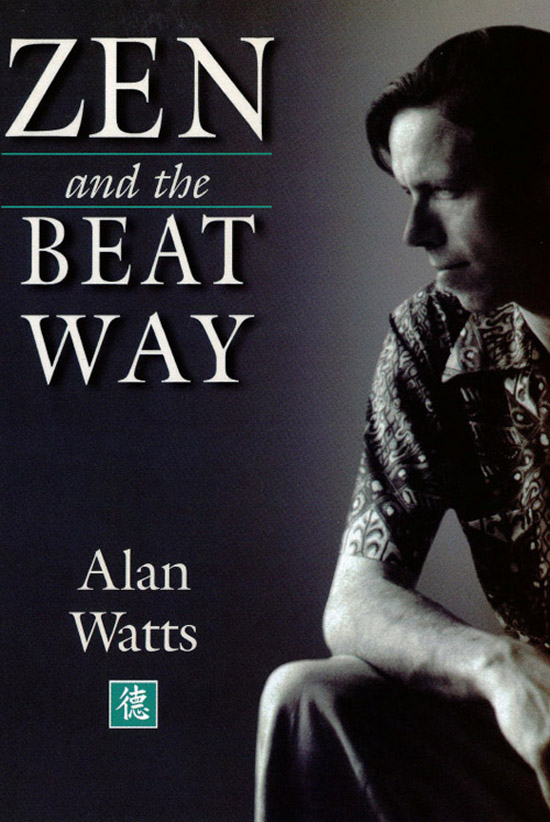

Zen and the Beat Way

First published in 1997 by Tuttle Publishing

an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd.

Copyright 1997 Mark Watts

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission from Tuttle Publishing.

The excerpt on page xviii-xix is from The Windbell, reprinted courtesy of Gordon Onslo-Ford and the San Francisco Zen Center.

Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data

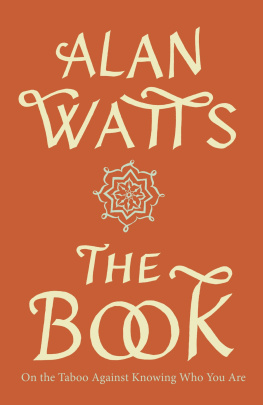

Watts, Alan, 1915- 1973.

Zen and the Beat Way/ Alan Watts.

p. cm.

Based on selections from Alan Watts's radio talks and tape recordings; adapted and written by David Cellers and Mark Watts.

Cf. CIP pref.

ISBN: 978-1-4629-0466-2 (ebook)

1. Zen Buddhism. l. Cellers, David. ll. Watts, Mark.

III. Title

BQ9266.W389 1997

294.3'927 --dc21

97-6843

CIP

Distributed by:

| Japan & Korea | North America | Asia Pacific |

| Tuttle Publishing | Tuttle Publishing | Berkeley Books Pte. Ltd. |

| Yaekari Building | Distribution Center | 61 Tai Seng Avenue, #02-12 |

| 3rd Floor, 5-4-12 | Airport Industrial Park | Singapore 534167 |

| Osaki Shinagawa-ku, | 364 Innovation Drive | Tel: (65) 280 1330 |

| Tokyo 141-0032 | North Clarendon, | Fax: (65) 280 6290 |

| Tel: (03) 5437 0171 | VT 05759-9436 |

| Fax: (03) 5437 0755 | Tel: (802) 773 8930 |

| Fax: (802) 773 6993 |

First Edition, 1997

Second printing, 2001

Design by Kathryn Sky-Peck

Printed in Singapore

Contents

vii

xi

CHAPTER ONE

1

CHAPTER TWO

CHAPTER THREE

CHAPTER FOUR

CHAPTER FIVE

CHAPTER SIX

Preface

Zen and the Beat Way is based upon selections from Alan Watts's early radio talks, many of which were first aired on the Pacifica Radio Network in the late fifties and early sixties, and sessions from two of his most compelling seminars in the mid-sixties. The original recordings have been adapted to the written page by David Cellers and Mark Watts.

Zen and the Beat Way is based upon selections from Alan Watts's early radio talks, many of which were first aired on the Pacifica Radio Network in the late fifties and early sixties, and sessions from two of his most compelling seminars in the mid-sixties. The original recordings have been adapted to the written page by David Cellers and Mark Watts.

Our first selection, "Introduction to the Way Beyond the West," was broadcast on KPFK in Los Angeles on November 6, 1959, and offered Southern Californians their first opportunity to listen to the popular Alan Watts series broadcast by KPFA in Berkeley during the previous six years. The second and third talks, "The Beat Way of Life" and "Consciousness and Concentration," were originally broadcast on KPFA on August 11 and 15, 1959, and shortly thereafter on KPFK. The radio series has continued on these stations in various forms for more than forty years. By the early sixties, tape recordings of public lectures, rather than radio talks, were being broadcast. Our fourth selection, "Zen and the Art of the Controlled Accident," was one such lecture, recorded in La jolla, California, in early 1965, and "The Democratization of Buddhism" was recorded while on tour in japan in 1963. The final selection, "Return to the Forest," was recorded in 1960 and includes a commentary on joseph Campbell's work on the earliest counterculture traditions.

Robert Wilson: What is Zen?

Alan Watts: [Soft chuckling.]

Robert Wilson: Would you care to enlarge on that?

Alan Watts: [Loud laughing.]

Introduction

During a 1960 "impolite interview" for Paul Krassner's free-thought magazine The Realist, Robert Anton Wilson asked Alan Watts what he thought about the Beat generation. Alan replied that the concept was "a journalistic invention, and having been invented and put on the market, many people bought it." Alan then began to reminisce about the real Beats:

During a 1960 "impolite interview" for Paul Krassner's free-thought magazine The Realist, Robert Anton Wilson asked Alan Watts what he thought about the Beat generation. Alan replied that the concept was "a journalistic invention, and having been invented and put on the market, many people bought it." Alan then began to reminisce about the real Beats:

Now, I remember the real, original Dharma Bums of the 1945-46 era-young veterans hitchhiking across the country and stopping every place there was a "sage" who knew something about Eastern philosophy. Some even went to Switzerland to speak to jung, and many came to see me at Northwestern University.

They weren't interested in jazz or drugs or hot rods, I assure you. Many of them are still around, but very few of them in the Village or North Beach. They're on farms or in little communities they created themselves. They are out of the rat races of keeping up with the joneses.

They are the substance of which the Beat generation is the shadow. [p.1]

By the late fifties the Beat movement was already a few incarnations removed from its origins, and clearly Alan Watts felt that Eastern thought had been inextricably tied to its genesis. And although it seems inevitable that many people will see the source of any social movement as its purest form, the phenomenon known as "the Beat way of life" was as much a reaction to the realities of mainstream American culture of that era as anything else. Politically, the 1950s were a dark period in American history. Cold-war paranoia found expression in McCarthyism and pitted the political process against free expression and the creative life. In the trials of Lenny Bruce and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, First Amendment rights came under attack. Today, freedom-of-speech questions are still judged according to their "redeeming social value," as they were in the trials of the fifties. The very act of being an artist or writer was in and of itself suspect, and the Beats reacted to the conservative climate with a well-balanced_synthesis of anarchism and idealism. But underneath this colorful social chaos, it is important to remember that originally the Beat movement was a way of life with connections to Zen, and from Zen to Hinduism, and from Hinduism back to the dawn of human culture.

Recently I came across the following passage in Robert Lawlor's captivating book on Australian Aboriginal culture, Voices of the First Day:

The materialistic industrial societies are increasingly caught in a round-the-clock whirl in which people are trapped, day after day, in a breathless grind of facing deadlines, racing the clock between several jobs, and trying to raise children and rush through the household chores at the same time. Agriculture and industrialism, in reality, have created a glut of material goods and a great poverty of time. Most people have a way of life devoid of everything except maintaining and servicing their material existence 12 to 14 hours every day. In contrast, the Aborigines [spent] 12 to 14 hours a day in cultural pursuit. [p. 65].

As Lawlor points out, "their traditional way of life provided more time for the artistic and spiritual development of the entire society. Dance, ritual, music-in short, culture-was the primary activity." The Aborigines passed the message of their ancestors down through a rich tradition of ritual storytelling, and their myths reflect the qualities of one of the oldest and most interesting surviving human cultures.

The Aboriginal view of creation is rooted in the idea of an original dreamtime, perhaps corresponding to a historical age, in which the conscious and unconscious aspects of mankind were unified "on the first day." Aboriginal ceremonies emphasize remembering that primal unity through ritual acts. According to their mythology, these ceremonies are visited by the Rainbow Serpent, described by Lawlor as "the original appearance of creative energy in the dream time." In the parallel Hindu myth of creation, the god Vishnu dreams the world into being while riding a great serpent in the cosmic ocean. In these Aboriginal and Hindu stories, one can see two similar tellings of the same essential myth.

Zen and the Beat Way is based upon selections from Alan Watts's early radio talks, many of which were first aired on the Pacifica Radio Network in the late fifties and early sixties, and sessions from two of his most compelling seminars in the mid-sixties. The original recordings have been adapted to the written page by David Cellers and Mark Watts.

Zen and the Beat Way is based upon selections from Alan Watts's early radio talks, many of which were first aired on the Pacifica Radio Network in the late fifties and early sixties, and sessions from two of his most compelling seminars in the mid-sixties. The original recordings have been adapted to the written page by David Cellers and Mark Watts. During a 1960 "impolite interview" for Paul Krassner's free-thought magazine The Realist, Robert Anton Wilson asked Alan Watts what he thought about the Beat generation. Alan replied that the concept was "a journalistic invention, and having been invented and put on the market, many people bought it." Alan then began to reminisce about the real Beats:

During a 1960 "impolite interview" for Paul Krassner's free-thought magazine The Realist, Robert Anton Wilson asked Alan Watts what he thought about the Beat generation. Alan replied that the concept was "a journalistic invention, and having been invented and put on the market, many people bought it." Alan then began to reminisce about the real Beats: