St Andrews Church, Roker, 190407, view of the tower and lady chapel in 1979.

( Nicholas Breach / RIBA Library Photographs Collection)

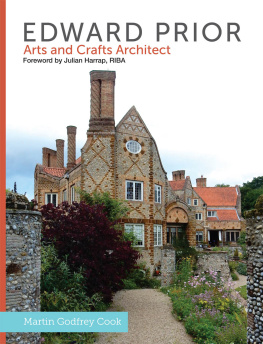

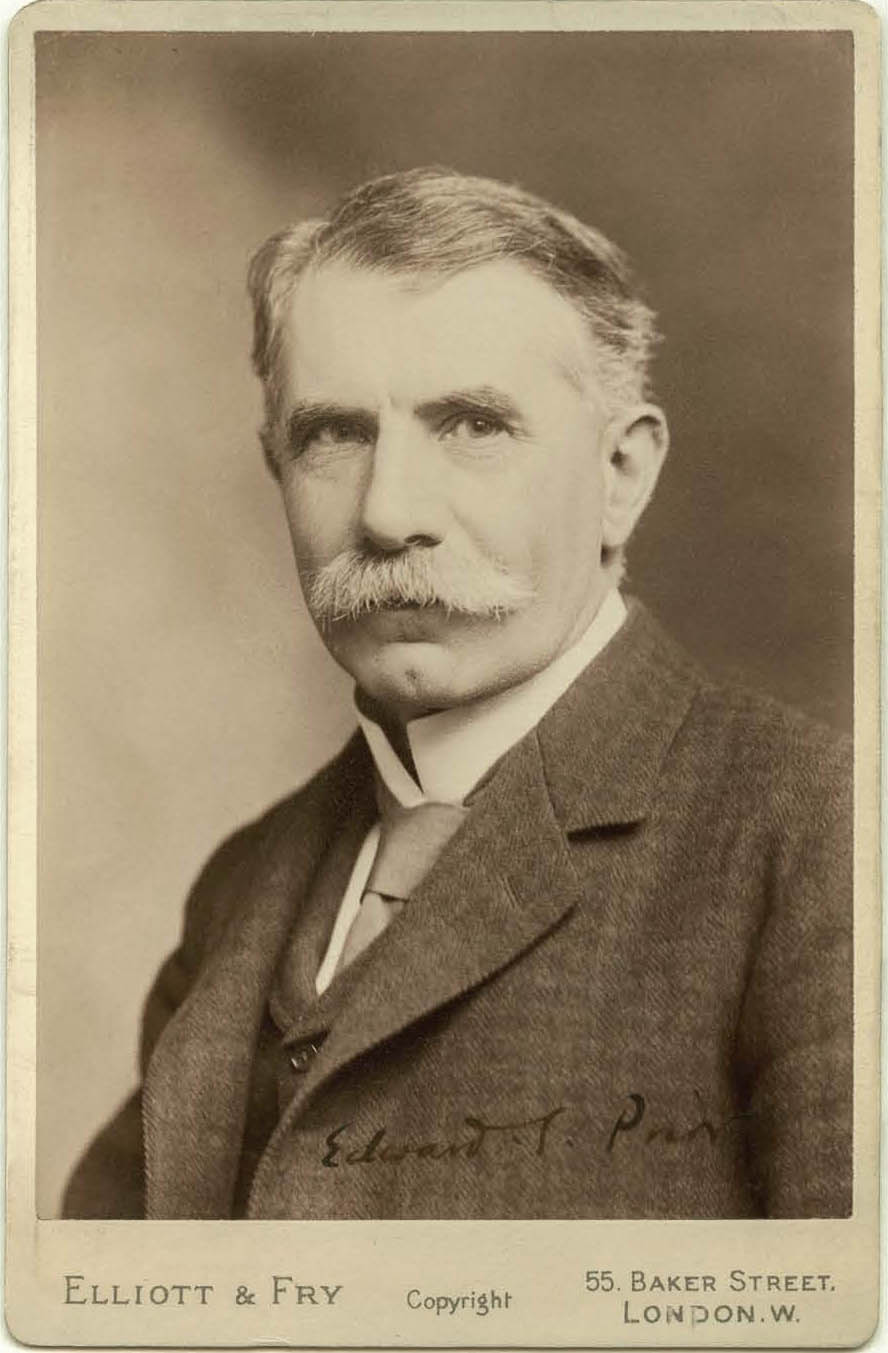

EDWARD PRIOR

Arts and Crafts Architect

Martin Godfrey Cook

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2015 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

Martin Godfrey Cook 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78500 012 6

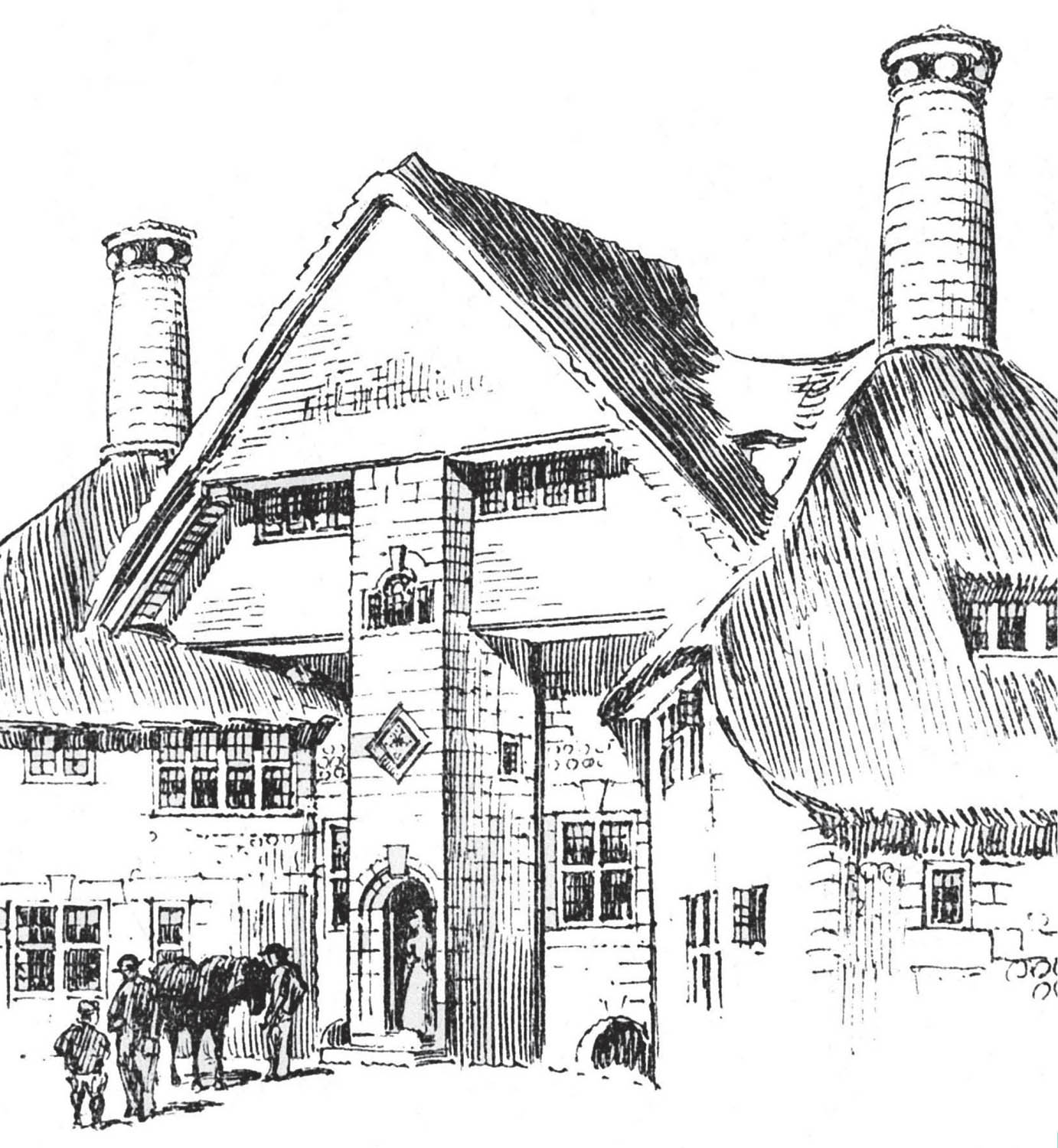

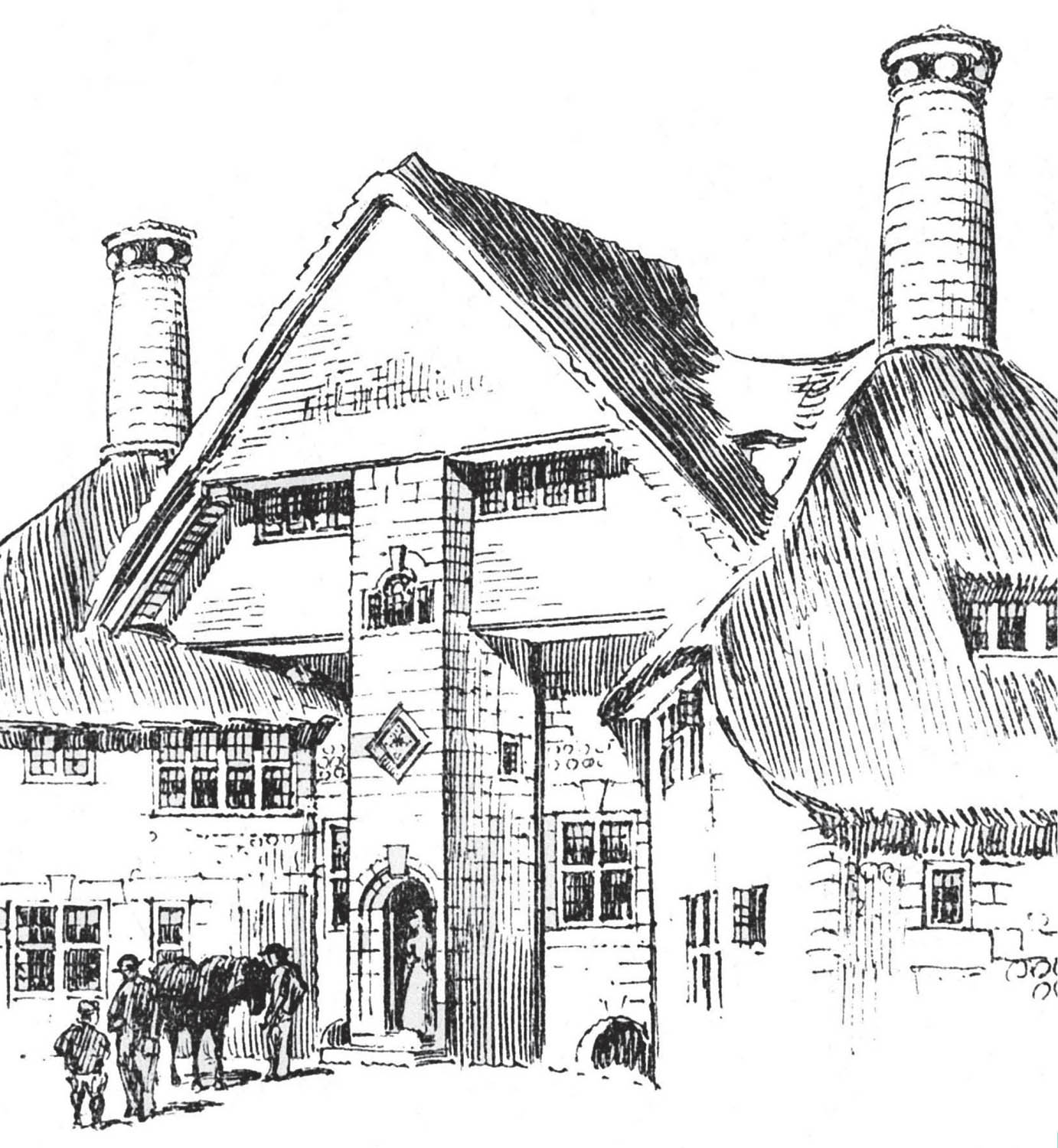

Frontispiece: The Barn, Exmouth, Devon, 1896, detail of sketch of the entrance elevation.

( RIBA Library Books & Periodicals Collection)

Contents

Chapter 1

PRELUDE

E DWARD S CHRODER P RIOR (18521932) IS worthy of more consideration than currently afforded to him in the annals of architectural history, which usually only includes passing mentions of his most strikingly original buildings. These invariably focus on his ecclesiastical masterpiece at St Andrews in Sunderland (1906), described as the cathedral of the Arts and Crafts Movement, and on his innovative butterfly-plan houses, The Barn at Exmouth in Devon (1896) and Voewood at Holt in Norfolk (1903). Comparatively little is known of his wider body of work, despite the emergence of some studies and publications over the years. Priors overall architectural output was not as prolific as the more commercial architects of his era. He clearly sought quality rather than quantity, and pursued originality with a rugged individualism. This invariably resulted in idiosyncrasy, innovation and ingenuity in the design and construction process as well as the architectural product.

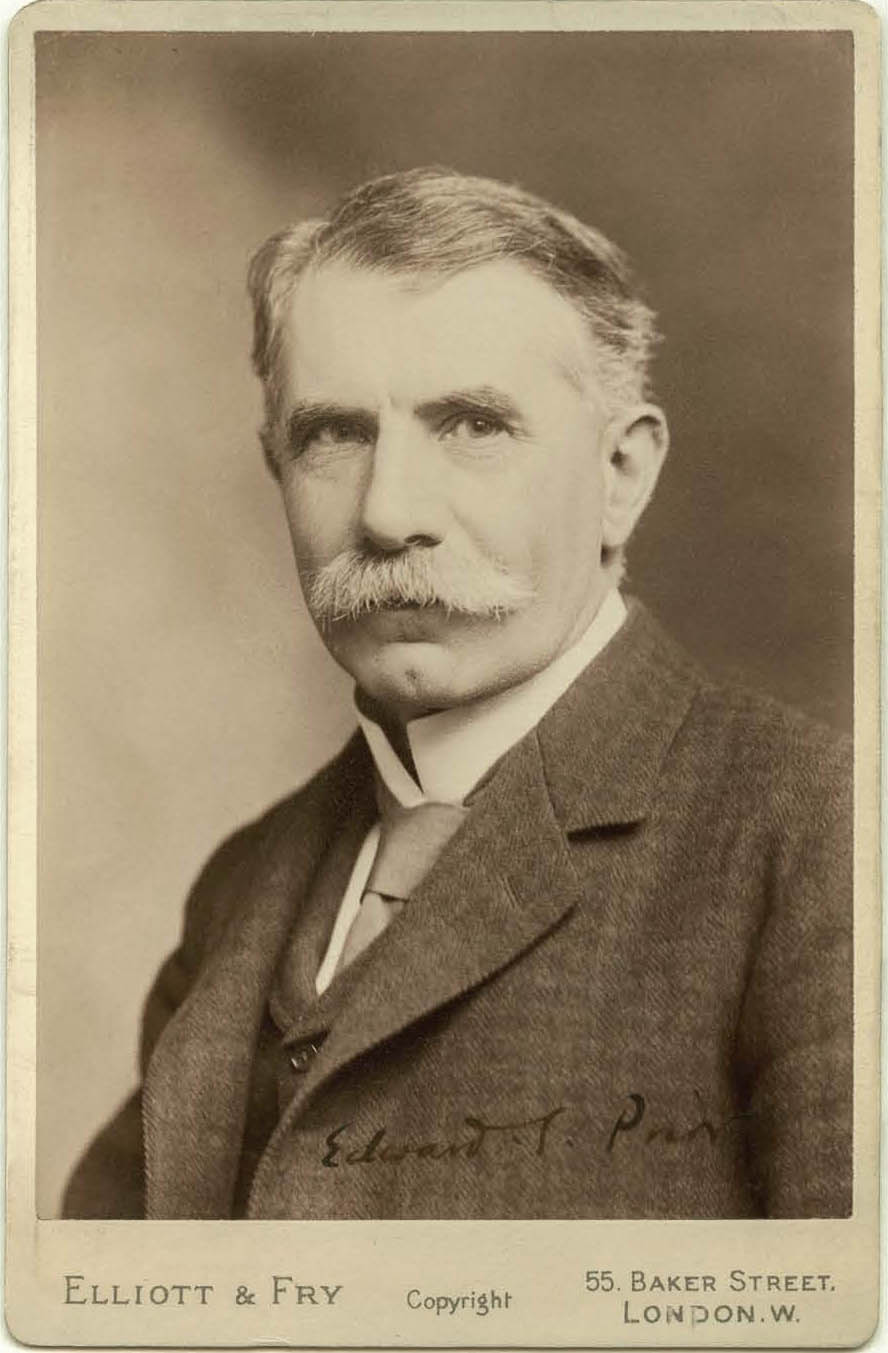

Edward Schroder Priors visiting card portrait, c. 1910.

( National Portrait Gallery)

The architectural historian Andrew Saint speculated that Edward Priors relative marginalization was either out of generosity or from difficulties of temperament. In spite of a series of daunting books and lectures on medieval art and a handful of designs of striking concentration and originality, Saint goes on to postulate that He perhaps failed to be the Webb of his generation because Lethaby and Voysey managed to split and share the mantle, and he could or would not spoil the award. If true, this reflects a gentlemanly approach that concurs with Priors romantic idealism, and his legacy certainly warrants reconsideration. A redressing of this historic imbalance is now long overdue, and it is now time to place Edward Prior in his rightful place in the pantheon of his architectural generation, and even that of architectural history in general.

St Andrews Church, Roker, Sunderland, 190407, view from the nave to the chancel.

The Barn, Exmouth, Devon, 1896, viewed from the south, showing the suntrap terrace.

Voewood, High Kelling, Norfolk, 190305, viewed from the south, over the croquet lawns.

The fact that the vast majority of Priors buildings have survived, in one form or another, is a solid testament to his architectural talent. Only about a tenth of his buildings have been demolished and two thirds of his remaining architecture benefits from legislative conservation protection several of these are Grade I listed. However, he did not confine himself to architectural practice, but continued his scholarly study of Gothic art and architecture throughout his life, resulting in four books. He also wrote many articles, for publications such as the Architectural Review, The Studio and other journals topics were wide-ranging, from garden design to architectural modelmaking. However, he was always uneasy with the inappropriateness of his classical education as a basis for architectural practice. Such misgivings may have sparked his interest in architectural education and his foundation of the School of Architecture at Cambridge University in 1912, including a proposed curriculum which presaged Walter Gropius 1919 Bauhaus manifesto in many respects.

Edward Prior was a seminal figure in the Arts and Craft Movement who produced some highly original works of architecture and carefully controlled his output to achieve the highest quality, both in design and materials. He largely succeeded in applying the artistic philosophies of Ruskin and Morris to architecture, and ultimately transcended them. Around half of Priors buildings were houses, in many cases late Victorian or Edwardian country houses, which have survived through changes of use to various forms of multi-residential type, such as hotels and student accommodation. Despite many Grade II and II* listings, this has often entailed considerable alterations to interiors to meet modern and fire safety requirements. Although much of the original interior spirit is often lost with these changes, the fact remains that the buildings are still in use a century or more after their construction and satisfactorily serving very different purposes. This serves as evidence of the quality of their construction and flexibility of design, at the very least. This is borne out by most of Priors architecture, as he invariably sought the best local materials and building techniques, and usually innovated in one way or another.

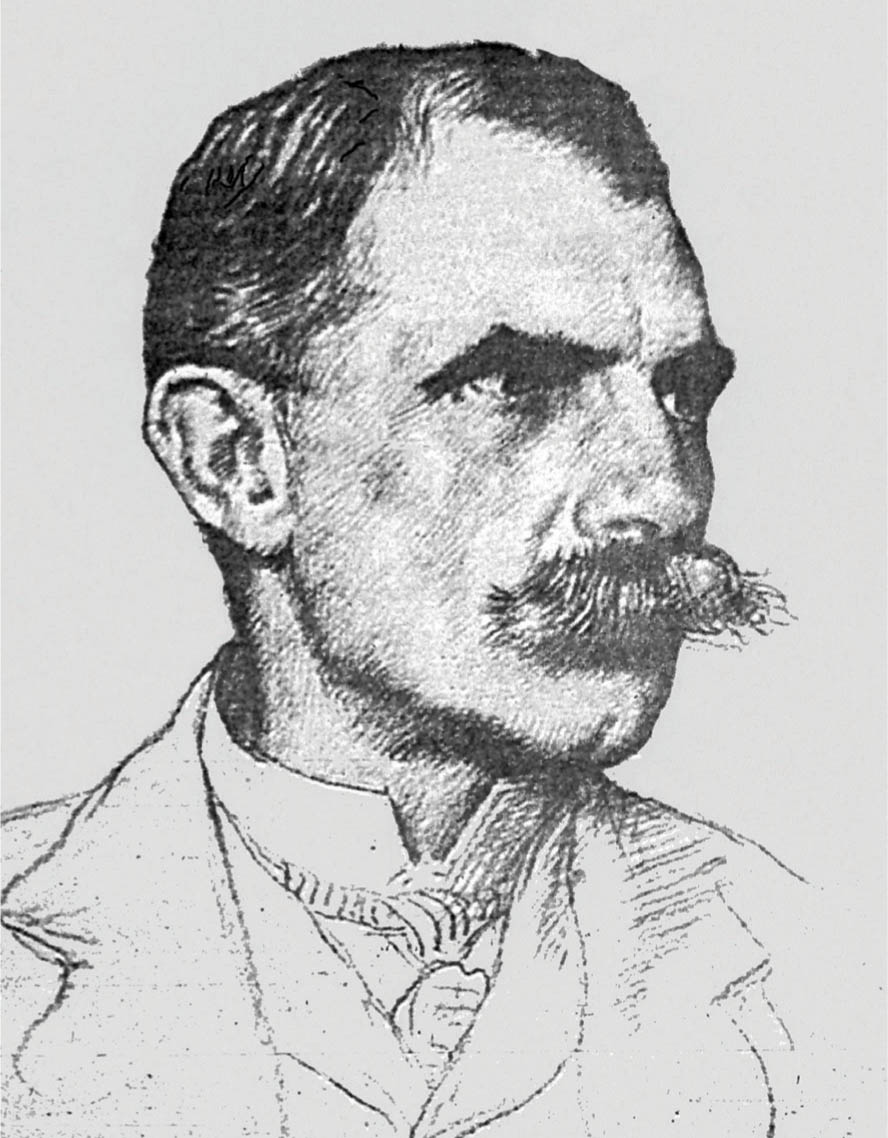

Portrait of Edward Prior by William Strang, 1907.

Possibly the main reason for the relative neglect of the wider body of Priors architecture is the perception that the thread he pursued led to a cul-de-sac. However, this bears reappraisal when viewed in the context of the architectural transitional phase of the two decades hinged around the fin de sicle. Priors domestic work must have inspired Dutch domestic Expressionism in the 1920s, and his large churches were forerunners of much German Expressionism of the same period. In this sense, Prior is viewed, by Nikolaus Pevsner, as a herald of the Modern Movement, spanning and inspiring a transition between medieval revivalism and early Modernism. However, Priors enigmatic quality of architectural expression is rarely conveniently categorized, and it is unlikely that Prior would have regarded such categorization in a flattering light. His early flirtation with literal historicism and vernacular revivalism, self-acknowledged homage to Norman Shaw and George Devey, was soon replaced by quirky attempts to forge a contemporary architecture. Prior is best likened to his almost exact contemporary, Antoni Gaudi, in his continuous exploration of eclecticism through to its inexorable outcome originality.

Next page