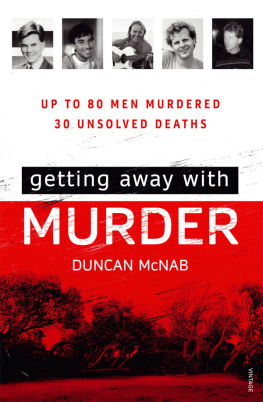

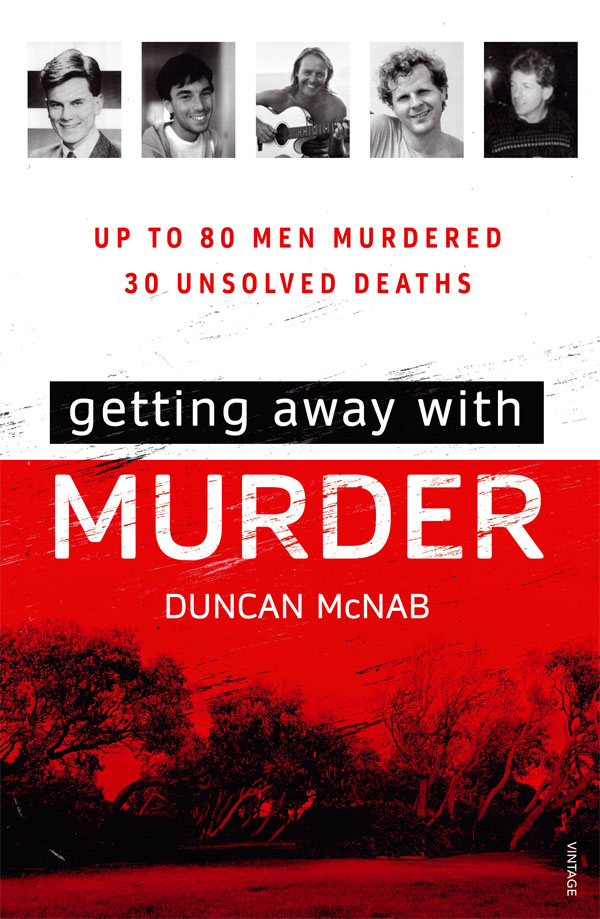

About the Book

Sydneys shame: Up to 80 men murdered, 30 cases remain unsolved.

From 1977 to the end of 1986, Duncan McNab was a member of the NSW Police Force. Most of his service was in criminal investigation. The many unsolved deaths and disappearances of young gay men are the crimes that continue to haunt him.

Around 80 men died or disappeared in NSW from the late 70s to early 90s during an epidemic of gay-hate crimes. The line between a vicious assault and murder is a slender one and this was a time of brutal attacks on gay men, featuring gangs of young thugs like the Parkside Killers and Bondi Boys, who took to the growing gay rights community with fists and feet.

Even more troubling are incidents in which gay men disappeared and have never been found, or where deaths were initially dismissed by the NSW Police as either misadventure or suicide. We now know that a number of these men were hunted down by gangs and thrown over beachside cliffs near the nations top tourist spots.

Investigation of crimes against gay men wasnt always high on the list of priorities for the police and over twenty years later they are still slow to come to grips with their own dismal track record. The families of the victims, and some journalists, have not given up and continue to push the NSW Police Force for more answers.

This book is the story of a unique time in our history when social change, politics, devastating disease and police culture collided, and you could get away with murder.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

THE MORE THINGS CHANGE

Just before midnight in the summer of 1981, an anonymous male made a call to the emergency line 000 from a public telephone box. Hed found an unconscious man in the mens toilet at the Collaroy Surf Club, but he didnt wait around for the emergency services to arrive.

First on the scene was an ambulance crew from nearby Narrabeen, who found a man in his late fifties face-down in the drain hole at the centre of the stainless-steel trough that lined one wall of the toilet. He was amid the beads that unsuccessfully tried to mask the smell of urine and provided target practice for generations of boys. The usual grate that covered the drain hole was missing, and the mans face was torn by the rough welds where the trough met the drainpipe. What was immediately apparent was that the man had been viciously assaulted. There was damage to the back of his head and neck caused by repeated blows, and probably broken fingers. His breathing was ragged. The ambulance officers called for police assistance and acted quickly and carefully to extricate the man and take him to the emergency unit at Mona Vale District Hospital, just under six kilometres away.

The uniformed police working the night shift at nearby Collaroy Police Station headed straight to the hospital. An examination of the man showed head injuries so severe that there was a risk of him dying or suffering extensive brain damage, so the doctors decided the safest course was to transfer him to the specialist care offered by Royal North Shore Hospital at St Leonards. While the medical staff were stabilising their patient and alerting their colleagues at North Shore, the police took brief details from the ambulance officers. The police searched the mans clothing and found his pockets empty: no wallet or car keys. He wasnt wearing the chunky identification bracelets that were chic at the time, or rings or pendants with any inscriptions, and he hadnt regained consciousness at any time. The mans identification was unknown, which was not unusual in cases that looked like an assault and robbery. The police knew from experience that it was a mystery likely to be resolved in daylight, long after theyd finished their shift at 7am and headed home to try to sleep through another hot, humid day.

The uniform coppers then went into the surf-club toilet, now a crime scene, and en route contacted the night-shift detectives who prowled the region from the Harbour Bridge to the south, Rydalmere to the west and Hornsby to the north. Their role was to triage serious crimes. It was either do the basics and leave it for the morning-shift detectives to follow up or, if the crime needed a full investigation to start immediately, get the local detective sergeant in charge out of bed, which he would in turn do to his staff. When the detectives joined the uniformed police at the toilet, they decided that little could be accomplished at night, and with the condition of the man still uncertain and no witnesses around, there was no rush. They made sure the scene was locked up and secure, took the registration details of the couple of cars in the car park, and left the uniformed coppers to track down the owners in the hope one would be the injured man, and alert Scientific the two detectives stationed at Chatswood who looked after all the forensic work on the north side of the harbour who would be needed when they came on duty in the morning.

At 8.30am I started my days duty at the Mona Vale detectives office. I was twenty-four years old and nearly two years into my training to be a detective. Id begun my police career at Manly, working there in uniform for eighteen months before being accepted into criminal-investigation training. After a few months working in the detectives office on A list then the first step of training I was sent to the famous or infamous, depending on your viewpoint No 21 Division at the Criminal Investigation Branch (CIB), which was the next obligatory step in an aspiring detectives career. At 21, we cruised Kings Cross and other crime hot spots looking for felons on the run or plotting deals, raced to be the first at crime scenes and learned how to drink both on and off duty. Dinner on a quiet afternoon shift was spent with the police truck parked outside Bill and Tonis in the little Italy of Stanley Street in East Sydney, with the windows wound down and the radio turned up so we could hear the calls from our table on the balcony above. On the menu was a plate of spaghetti Bolognese or the minestrone along with bread and iceberg lettuce, followed by schnitzel with cheese. We skipped the free cordial unless the night was stinking hot, and instead watered ourselves from a flagon of red bought at the Lord Roberts pub on the corner.

The less desirable duties at 21 included trying to catch SP book-makers in hotels a role at which I was lousy because I looked too much like a schoolboy on an excursion to the wrong place raiding casinos, arresting drunks to get them off the street and let them sober up in the cells, and peanutting, which was the dying art of loitering around public toilets or parks in the hope of being propositioned by another man, and then arresting the poor sod.

Working in a backwater like Mona Vale had been surprisingly instructive. For my first few months Id been paired with George Hunter, the former rugby league star and a man who seldom strayed from either the office or his table at the Manly Warringah Leagues Club. George ended his career a few years later when he was arrested and sent to prison for his role in a large marijuana deal. Id worked on two murder investigations in the eighteen months I was stationed out there; on both occasions I was one of the first through the door to arrest the killers but sidelined for the interviews. It was the days of the unsigned record of interview in which the culprit allegedly confessed to some useful points in the investigation of the crime, but declined to sign the interview. Sometimes this actually happened, but in many cases the record of interview was a neatly concocted script written by the detectives then presented to the court as a persuasive document. It is one of the reasons the introduction of tape-recording interviews became an imperative.