But I dont want to go among mad people, Alice remarked.

Oh, you cant help that, said the cat: were all mad here. Im mad. Youre mad.

How do you know Im mad? said Alice.

You must be, said the cat, or you wouldnt have come here.

Chapter 1

If all werent a little mad wed be totally insane.

Stacy Lucero

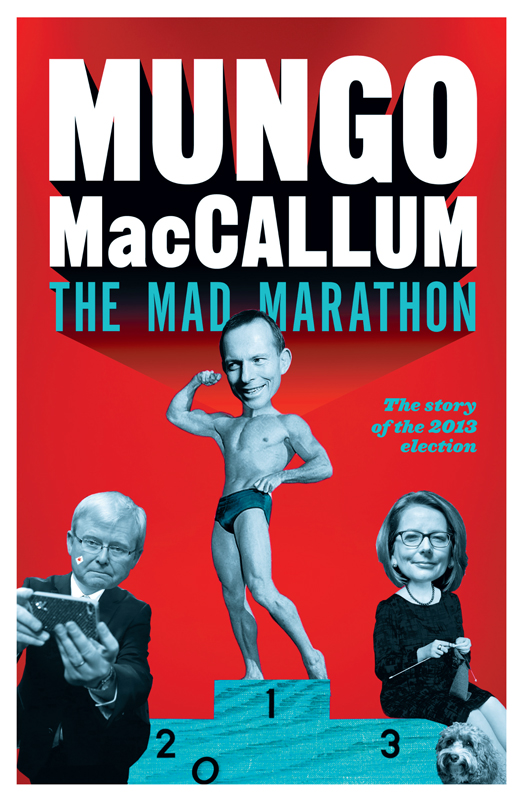

The year 2013 began with fire and destruction, tumult and terror; but the overture came as no surprise to either triskaidekaphobes or psephologists. Sure, the Mayans had predicted the world would end on 21 December 2012, but what did they know? The Mayans had never had to suffer through a federal election year in Australia, always an occasion for wailing and gnashing of teeth, but in 2013 holding the real possibility of apocalypse.

Already the four horsemen were abroad, spreading war, setting the scene for Armageddon, the final battle between good and evil or, depending on your point of view, between evil and good. The most rational response for the majority, who didnt like either side very much, was to dive into a deep hole and pull the hole in after them. But alas, for all too many of us that option was not open, so we assumed our normal role as innocent bystanders, glued to the unfolding of that strange and terrible drama known as the campaign.

In practice, of course, it had started long ago; indeed, a cynic might have said that the last election, in 2010, had been little more than a punctuation mark in the epic vendetta between the Red Witch and the Mad Monk, as they were unaffectionately known to an exhausted and exasperated media. For the best (or worst) part of three years, Julia Gillard and Tony Abbott had been sniping at each other, inflicting numerous ugly flesh wounds but unable to strike the mortal blow.

However, some of the scars were permanent. Much of the electorate now saw Gillard as a liar, unwilling to keep her promises and, on the rare occasions she did, unable to deliver on them. Her government, if not downright illegitimate, was untrustworthy and incompetent, compromised beyond all hope of redemption. Abbott, on the other hand, had assumed the mantle of a conservative, sloganeering, utterly negative bigot, with no interest in public policy and not much in anything other than his body and his ambition. If not actually a misogynist, he was deeply sexist, uncomfortable with women and immured in a medievalist view of the world, which he planned to visit upon the rest of us if we gave him half a chance.

To call the choice uninviting was like describing Hades as a trifle warm for a relaxing holiday. But it was the only choice we had, so we watched gloomily as they fronted the cameras for their new years messages, which, almost identically, spoke of their optimism and confidence for the year ahead. Almost immediately the bushfires began. Even to convinced atheists it had the appearance of divine retribution.

But at least one convinced atheist, the prime minister herself, was unfazed. She had already got out of the blocks early with an appearance at the Woodford Folk Festival, where she took part in a love-in (verbal, that is) with Bob Hawke an act for which Malcolm Turnbull obligingly provided the curtain-raiser. Now she invited the Australian cricketers and the touring Sri Lankan team to Kirribilli House for new years drinkies and to cavort with her cavoodle Reuben, in both of which activities they obliged. In return, she attended Jane McGrath Day at the Sydney test match and, after giving a large sum of money to the cause, was generously applauded by the crowd surely a first for a politician interrupting a sporting function.

There was also a more solid reason for her to feel that she was perhaps, at last, moving forward. The last Newspoll of 2012 had the two-party preferred vote locked at 5446 in favour of the Coalition right where it had been nearly twelve months previously. A later, more discursive analysis seemed to put the real figure at 5248. Abbott was still headed for a win, but from Labors point of view it wasnt nearly as bad as the indefatigable Dennis Shanahan tried to portray in his accompanying comment piece. When the next Newspoll showed the gap narrowing further, to 5149, Labor could, for the first time in three long years, claim to be back on track.

So we had a contest, and a bitter and even ugly one it might turn out to be, because it could only end with the destruction of one or the other of the combatants. Neither Gillard nor Abbott could survive defeat at the polls, and they knew it. This was a fight to the political death. But first, both would have to survive in their respective positions until the election was called. And while Gillard now looked safe enough from any resurgence by Kevin Rudd, it seemed that Abbott, incredibly, could just possibly be vulnerable.

*

A year earlier, this assertion would have been preposterous; by almost any measure, the man who had been thrust into the leadership almost by accident was the most successful opposition leader in many years. Abbott had already seen off one prime minister, and hed given his party what looked like an unassailable lead in the opinion polls.

Most importantly, there was no credible challenger within his ranks. True, there were some who remained uneasy about his undeviating aggression, his take-no-prisoners approach to every issue, however subtle and complex; there were well-grounded fears that it could rebound on him and the Liberal Party, especially with his apocalyptic pronouncements on the carbon tax. There were those who yearned for the insurance a little more nuance might provide.

But to these doubters, Abbotts army of supporters in the party room and the media replied simply: Look at the scoreboard. Their man was firmly on track to lead the Coalition back to its rightful place on the Treasury benches, and in the long term and the short and medium terms too that was all that mattered.

During 2012, however, things had become a little less certain, and the great paradox of Tony Abbott had started to emerge. Sure, he had put his party in a winning position, but he was also the lead in its saddlebags. If anyone could snatch defeat from the jaws of victory, it was Abbott.

Although the Coalition remained in front in the polls, Abbott himself was deeply unloved by a growing majority of the electorate. The voters didnt like Julia Gillard much either, but the feeling that had prevailed for so long that the Labor government was so horrible that the voters were willing to pay any price to get rid of it, up to and including installing Abbott as prime minister no longer applied. If the voters had to choose a prime minister, most preferred Gillard. This did not mean that they couldnt be persuaded to close their eyes, hold their noses and elect Abbott, if only to get rid of the minority Labor government, but it did mean that a lot of them were far from enthusiastic about the prospect.