Contents

About the Book

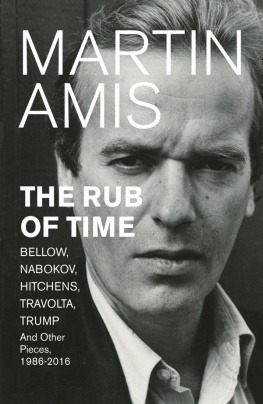

Of all the great novelists writing today, none shows the same gift as Martin Amis for writing non-fiction his essays, literary criticism and journalism are justly acclaimed. As Rachel Cusk wrote in the The Times, reviewing a previous collection, Amis is as talented a journalist as he is a novelist, but these essays all manifest an unusual extra quality, one that is not unlike friendship. He makes an effort; he makes readers feel that they are the only person there.

The essays in The Rub of Time range from superb critical pieces on Amiss heroes Nabokov, Bellow and Larkin to brilliantly funny ruminations on sport, Las Vegas, John Travolta and the pornography industry. The collection includes his essay on Princess Diana and a tribute to his great friend Christopher Hitchens, but at the centre of the book, perhaps inevitably, are essays on politics, and in particular the American election campaigns of 2012 and 2016. One of the very few consolations of Donald Trumps rise to power is that Martin Amis is there to write about him.

About the Author

Martin Amis is the author of fourteen novels, the memoir Experience, two collections of stories and six collections of non-fiction. He lives in New York.

Also by Martin Amis

FICTION

The Rachel Papers

Dead Babies

Success

Other People

Money

Einsteins Monsters

London Fields

Times Arrow

The Information

Night Train

Heavy Water

Yellow Dog

House of Meetings

The Pregnant Widow

Lionel Asbo

The Zone of Interest

NON-FICTION

Invasion of the Space Invaders

The Moronic Inferno

Visiting Mrs Nabokov

Experience

The War Against Clich

Koba the Dread

The Second Plane

To Isaac and Eleanor

By Way of an Introduction

Hes Leaving Home

Once upon a time, in a kingdom called England, literary fiction was an obscure and blameless pursuit. It was more respectable than angelology, true, and more esteemed than the study of phosphorescent mould; but it was without question a minority-interest sphere.

In 1972, I submitted my first novel: I typed it out on a second-hand Olivetti and sent it in from the sub-editorial office I shared at the Times Literary Supplement. The print run was 1,000 (and the advance was 250). It was published, and reviewed, and that was that. There was no launch party and no book tour; there were no interviews, no profiles, no photo shoots, no signings, no readings, no panels, no on-stage conversations, no Woodstocks of the Mind in Hay-on-Wye, in Toledo, in Mantova, in Parati, in Cartagena, in Jaipur, in Dubai; and there was no radio and no television. The same went for my second novel (1975) and my third (1978). By the time of my fourth novel (1981), nearly all the collateral activities were in place, and writers, in effect, had been transferred from vanity press to Vanity Fair.

What happened in the interim? We can safely say that as the 1970s became the 1980s there was no spontaneous flowering of enthusiasm for the psychological nuance, the artful simile, and the curlicued sentence. The phenomenon, as I now see it, was entirely media-borne. To put it crudely, the newspapers had been getting fatter and fatter (first the Sundays, then the Saturdays, then all the days in between), and what filled these extra pages was not additional news but additional features. And the featurists were running out of people to write about running out of alcoholic actors, neer-do-well royals, depressive comedians, jailed rock stars, defecting ballet dancers, reclusive film directors, hysterical fashion models, indigent marquises, adulterous golfers, wife-beating footballers, and rapist boxers. The dragnet went on widening until journalists, often to their patent dismay, were writing about writers: literary writers.

This modest and perhaps temporary change in status involved a number of costs and benefits. A storyteller is nothing without a listener, and the novelists started getting what they cant help but covet: not more sales necessarily, but more readers. And it was gratifying to find that many people were indeed quite intrigued by the business of creating fiction: to prove the point, one need only adduce the fact that every last acre of the planet is now the scene of a boisterous literary festival. With its interplay of the conscious and the unconscious, the novel involves a process that no writers, and no critics, really understand. Nor can they quite see why it arouses such curiosity. (Do you write in longhand? How hard do you press on the paper?) All the same, as J.G. Ballard once said, readers and listeners are your supporters urging on this one-man team. They release you from your habitual solitude, and they give you heart. So far, so good: these are the benefits. Now we come to the costs, which, I suppose, are the usual costs of conspicuousness.

Needless to say, the enlarging and emboldening of the mass-communications sector was not confined to the United Kingdom. And visibility, as Americans call it, was no doubt granted to writers in all the advanced democracies with variations determined by national character. In my home country, the situation is, as always, paradoxical. Despite the existence of a literary tradition of unparalleled magnificence (presided over by the worlds only obvious authorial divinity), writers are regarded with a studied scepticism not by the English public, but by the English commentariat. It sometimes seems that a curious circularity is at work. If it is true that writers owe their ascendancy to the media, then the media has promoted the very people that irritate them most: a crowd of pretentious and by now quite prosperous egomaniacs. When writers complain about this, or about anything else, they are accused of self-pity (celebrity whinge). But the unspoken gravamen is not self-pity. It is ingratitude.

Nor should we neglect a profound peculiarity of fiction and the column inches that attend it: a fortuitous consanguinity. The appraisal of an exhibition does not involve the use of an easel and a palette; the appraisal of a ballet does not involve the use of a pair of slippers and a tutu. And the same goes for all but one of the written arts: you dont review poetry by writing verse (unless youre a jerk), and you dont review plays by writing dialogue (unless youre a jerk); novels, though, come in the form of prose narrative and so does journalism. This odd affinity causes no great tension in other countries, but it sits less well, perhaps, with certain traits of the Albionic Fourth Estate emulousness, a kind of cruising belligerence, and an instinctive proprietoriality.

Conspicuous persons, in my motherland, are most seriously advised to lead a private life denuded of all colour and complication. They should also, if they are prudent, have as little as possible to do with America seen as the world HQ of arrogance and glitz. When I and my wife, who is a New Yorker, entrained the epic project of moving house, from Camden Town in London to Cobble Hill in Brooklyn, I took every public opportunity to make it clear that our reasons for doing so were exclusively personal and familial, and had nothing to do with any supposed dissatisfaction with England or the English people (whom, as I truthfully stressed, I have always admired for their tolerance, generosity, and wit). Backed up by lavish misquotes together with satirical impersonations (cod interviews and the like), the impression given was that I was leaving because of a vicious hatred of my native land and because I could no longer endure the well-aimed barbs of patriotic journalists.