I have not winced nor cried aloud.

My head is bloody, but unbowed.

Finds and shall find me unafraid.

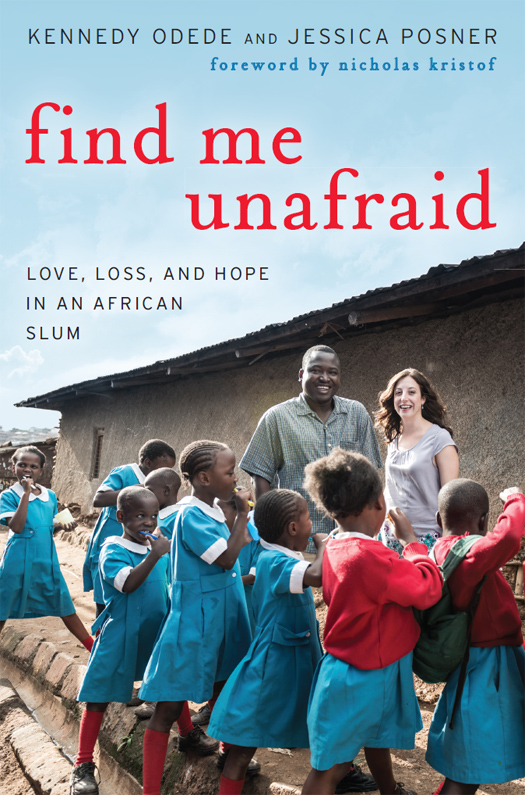

Ive seen lots of unlikely sights in my travels as a journalist and author, but one of the most remarkable is deep within the Kibera slum in Kenyas capital, Nairobi. Kibera is not at first glancehow can I say this politely?an uplifting place. Its a warren of tiny shacks on dirt paths that turn into mud and muck when it rains. Crime, joblessness, and sexual violence are common. The Kenyan authorities have offered little help, and Western aid projects havent done much to create opportunity either.

Yet you amble down one of these tiny dirt paths, turn a corner, and there it is, a modern, cheerful school full of bubbly elementary school girls in neat uniforms, and a large sign: KIBERA SCHOOL FOR GIRLS.

What girls these are! Theyre chattering away in English (for many of them, its their third language after Swahili and a tribal language), while brimming with poise and self-confidence. In class, they ace standardized exams and do better than wealthier students at much more privileged schools. The contrast between the hopefulness of these schoolgirls and their sometimes grim surroundings is strikingand its pretty clear that these girls are change-makers who will build a better Kibera, and a better Kenya.

Yet the Kibera School for Girls isnt just an education story; its also a love story. The school is the brainchild of Kennedy Odede, who grew up in the slum, and Jessica Posner, a Colorado girl who took a junior year abroad to work on street theater with Kennedy in Kibera. Jessica insisted on staying with Kennedy and his family, horrifying them allNo white person has ever stayed in Kibera!but she browbeat them and then, when she saw the rats and toilets and was privately aghast, was too stubborn to back down. Kennedy and Jessica learned from each other, she helped him get into Wesleyan University on a full scholarship (even though he had no SAT score or high school transcript), and together by force of will they built the Kibera School for Girls and a broader development effort called SHOFCO, or Shining Hope for Communities. It includes a clinic, a water source, economic empowerment programs, a community newspaper, a womens empowerment group, an effort to fight rape, and so much more, and is now expanding this model across Kenyas slums.

SHOFCO is a love story, but its also a lesson in development. The organization succeeded in part because it had someone with local knowledge and charisma to lead the way, and in part because it had a policy wonk foreigner who could help open overseas wallets. Thats a potent partnership. If its just foreigners, theres a risk that locals will see them as cows to be milked, or that a project wont have the necessary buy-in from local people. Indeed, SHOFCO is successful partly because it didnt begin as an aid program at all but as a local empowerment movement, with Kennedy and his buddies organizing soccer games and street performances decrying rape. Only after it was well established did it take on a more structured dimension, building effective partnerships.

Kennedys life underscores one of my favorite aphorisms: Talent is universal, but opportunity is not. Everyone who encounters Ken can see his prodigious gifts of leadership and enthusiasm, but even he could have easily gone in a wrong direction. He tried his hand at thievery but fortunately he turned out to be a wretched mango thief and was so scared when he was caught that he mostly stayed honest after that. He did fall in with a gang, though, and sometimes his anger and frustration boiled over and led him on a path toward violence. But, ultimately, he applied his talents to building and creating, not to destroying, and aspiration trumped frustration. So many people helped him, from childhood buddies to an Italian priest to Wesleyan admissions officers, and in the end it all came together. But to see Kennedy, or to see the brilliant and self-confident girls at the Kibera School for Girls, is to know that there are many other outstanding young children who wont get the opportunities they need. They lose, and so does the world.

Theres a theory that cycles of poverty perpetuate and self-replicate in part because of despair. People feel hopeless, and then engage in self-destructive behaviors that make that hopelessness self-fulfilling. The implication, and theres a fair amount of evidence emerging for this, is that the way to break cycles of poverty is to give people hopeand in the largest sense, thats what Kennedy and Jess are doing. They provide education, water, medicine, and more, but above all they provide a vision of hope, a trajectory toward a better life, a reassurance that maybe Kibera and indeed the worlds slums can become better places. Thats why my wife, Sheryl WuDunn, and I wrote about Ken and Jess in our own book A Path Appears as an example of how a cross-country partnership can fight poverty and spread opportunitywith hope!

Too often, humanitarians and journalists alike depict global poverty as uniformly bleak and grim. Aid groups do that because they think the way to raise money is to say how awful things are; journalists do it because were in the business of covering planes that crash, not those that take off. But the unrelenting focus on troubles masks the progress and risks turning the public off. The remarkable story of Kennedy and Jess makes a fine antidote to that gloom. Sure, they faced enormous obstacles, but ultimately their personal and professional saga is uplifting, hopeful, and thrilling. And I hope you have the chance someday not only to read their incredible tale but also to see their lifes work, taking a winding mud path through Kibera, only to turn a corner and findsomething close to a miracle.

december 2007

The wall of discarded milk cartons is the only barrier between me and the gunfire outside. On a normal night, the noises of Kibera drift easily through these walls: reggae music, women selling vegetables by candlelight, drunken men shouting insults, dogs barking, a couple making love in their nearby shack. But now Kibera is frozen. The entire slum is holding its breath, praying for this rain of bullets to pass, like any other storm.

Im shivering under the bed. Its so dark and breathing is difficult. I can feel spiders crawling over my back and rats poking my toes, but I stay still, afraid that any movement will draw the uniformed men. I hear a high-pitched scream, like that of a young girl. The uniformed men are spraying bullets, and they hit anyone or anything unlucky enough to cross their path. I close my eyes and pray that the girl will survive. They didnt come to Kibera for her. They came for me.

I havent eaten since yesterday when the raids began; Im starving for both water and food. In my pocket I have two dollars, which could ordinarily sustain me for at least a week. But even if I came out of hiding, there would be nowhere to get food. All the shops in the neighborhood have been closed or looted. The road going into Kibera has been shut by the mobs and men in uniformsparamilitary police. Nothing and nobody comes in and out without a struggle. They are sealing us in to die.