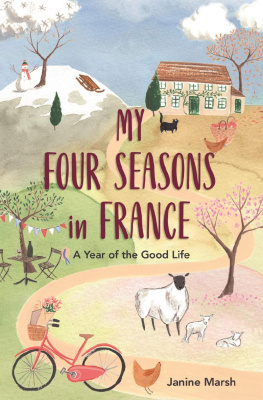

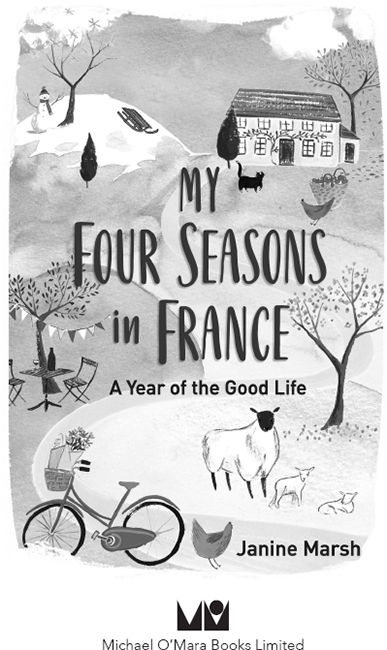

| My Four Seasons in France : A Year of the Good Life (2020) |

| Marsh, Janine |

|

A little over ten years ago, Janine Marsh and her husband Mark gave up their city jobs in London to chase the good life in the countryside of northern France.

Having overcome the obstacles of starting to renovate her dream home - an ancient, dilapidated barn - and fitting in with the peculiarities of her new neighbours, Janine is now the go-to expat in the area for those seeking to get to grips with a very different way of life.

In the Seven Valleys, each season brings new challenges as well as new delights.

Freezing weather in February threaten the lives of some of the four-legged locals - snow in March results in a broken arm, which in turn leads to an etiquette lesson at the local hospital - and a dramatic hailstorm in July destroys cars and houses, ultimately bringing the villagers closer together.

With warmth and humour, Janine showcases a uniquely French outlook as two eternally ambitious expats drag a neglected farmhouse to life and stumble across the hidden gems of this very special part of the world.

Also by Janine Marsh

My Good Life in France

First published in Great Britain in 2020

by Michael OMara Books Limited

9 Lion Yard

Tremadoc Road

London SW4 7NQ

Copyright Janine Marsh 2020

All rights reserved. You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-78929-047-9 in paperback print format

ISBN: 978-1-78929-048-6 in ebook format

www.mombooks.com

Cover illustration by Emma Block

To Mark, who made me take a leap of faith.

We travel not to escape life, but for life not to escape us.

Contents

IT ALL BEGAN on a freezing February day in 2004. My husband Mark and I had embarked on a day trip to Calais to buy wine with my dad, Frank, who had taken to drinking way too much whisky in order to drown his sorrows after my mum died a couple of years earlier. He was utterly lost without the love of his life and had taken to counting every day he had been without her. Whenever we spoke, he would say, You know, its been four hundred days since your mother died, and so on. It was so clear to me how much he thought of her and missed her every day, and I worried about him constantly. I thought that wine would be an improvement for him over the hard stuff, and that a trip with us might cheer him up a bit. And where better to pick up some wine than in France?

That morning, we picked up Dad from his home, not too far from ours in south-east London, and drove down to Dover, where we boarded a ferry to France under a wretched, ominously grey sky. The miserable weather certainly didnt improve when we reached Calais, with a gale coming in from the English Channel and buffeting the coast. After we had bought our wine, we decided to head inland from the coast to find somewhere cosy for lunch. We stopped off in the little town of Hesdin in the Seven Valleys, which, judging by the map, looked like it would be big enough to offer a grand choice of restaurants. Cobbled streets glistened under a steady stream of sleet as, wrapped up against the chilly wind, we searched for a place to eat. Alas we were too late. We didnt know it then, but restaurants in France are generally not an all-day affair and arriving at 1.30 p.m. will likely result in a non when you want a table.

Blimey, said Dad, you wouldnt want to live here, would you?

En route back to the car, soggy and fed up, we passed many cafs and bistros that looked teasingly tempting, with their warm glowing lights and oh-so-French menus. As we stopped to look at houses for sale in an estate agents window, the agent inside must have spotted our miserable, frozen faces and so he invited us in for coffee. It was too much of an enticement for my coffee-loving dad, and we trotted in behind him.

We were warmed by his generosity and the cosy interior of the shop, so the agent seized his chance: Ow much moanee are you looking to spend? he asked.

I choked on the strong French coffee and assured him we had no money and we werent looking for a house in France. Refusing to accept that we werent interested in buying, the agent used every ounce of charm he could muster, and after realizing we were too poor to buy a house that didnt need completely doing up, he pulled out his three cheapest properties. He worked so hard to persuade us that I gave in and, thanking him for the coffee, took the details and bade him au revoir, certain we would never see him again.

Back in the car, we considered going straight home. Or we could just take a look at these houses. Theyre all under a hundred thousand euros, I said. Buying a house in France wasnt something Id considered. But, a whole house for less than 60,000 you couldnt get a garage in London for that. I was intrigued. And the agent was a good salesman, piquing my interest with his descriptions of vaulted cellars, wood-panelled lounges and bedrooms suitable for a queen.

My suggestion was met with silence in the car. I wasnt sensing a great deal of enthusiasm from either of them. Theyre all in towns close to Hesdin. There might be a caf open in one of them, and its on the way back to Calais anyway, via the scenic route, I continued.

Tempted by the prospect of a local caf that might serve hot food, the unhappy men caved in to my suggestion. We drove for thirty minutes and arrived in a town that had a single road and a town hall, but no caf. The house for sale was in a semi-derelict state.

In the next town, there were just a few houses on a single road. On peering through the windows of the apparently fit for royalty house we could see that the walls, ceilings and even the doors were covered in hideous 1970s linoleum. It looked like a serial killers den.

The last house was in a tiny village with no shops, no bars and no sign of life. I was starting to think that driving here to view a house we didnt want and couldnt afford, even though it cost less than a Herms handbag, was probably a bit mad. By now, both Dad and Mark were seriously fed up.

I got out of the car to peer through a broken gate set into an unattractive concrete wall. Behind the wall was a very long and low detached farmhouse-style building with drab grey walls and a concrete-block extension. Paint was peeling from the windows and door, and the rain, pelting down on the moss-covered roof, spilled over gutters and gushed from a broken drainpipe. The rain-sodden front garden was filled with piles of broken bricks and rubble. The house looked abandoned.

Lets just go, said Dad. But, just as I turned to get into the car, the rain stopped and a beam of sunlight broke through the dark clouds. A man came out of the house and asked in English if he could help us. The church bells in the village started to ring and I heard ducks quacking loudly close by. I didnt know it then, but it was the sound of fate.