In a handful of instances in this book I have used pseudonyms for some of the humans, in order to protect the privacy of the dogs.

Im always grateful to hear from readers. My email is jb@jenniferboylan.net .

while you gently brush my hair.

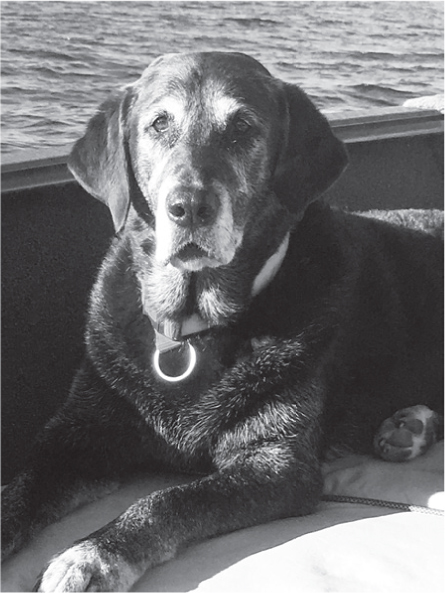

I took her picture one sparkling autumn day, as she stood in our dirt road waiting. There was a bright red maple leaf on the ground.

A year later, I held that photo in my hands as the tears rolled down. An Eva Cassidy ballad, Autumn Leaves, played on the radio. It was an old sad song.

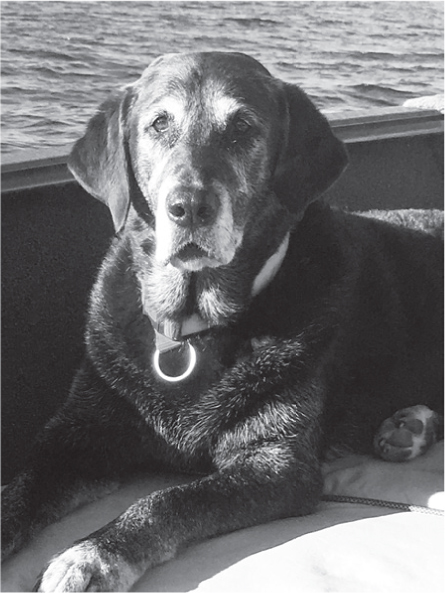

My children had been twelve and ten back in 2006. Our family had been through a wrenching couple of years. And yet wed emerged on the other side of those days still together, the four of us plus Ranger, the black Lab. Our lives revolved around that dog and each other.

But we worried that Ranger felt puny when we werent around. Sometimes we arrived back at the house to hear him howling piteously. It was heartbreaking, his loneliness.

Then, someone emailed us about this dog named Indigo. Shed had puppies a few months before, and now she needed a home. Were the Boylans interested?

The Boylans were.

Indigo joined us as Rangers wing-dog. When she first stepped through the door, her underbelly still showed the recent signs of the litter shed delivered. Between the wise droopy face and the swinging dog teats, she was a sight to behold.

She had a nose for trouble. On one occasion, I came home to find that shed eaten a five-pound bag of flour. She was covered in white powder, and flour paw prints were everywhere, including, incredibly, the countertops. I asked the dog what the hell had happened, and Indy just looked at me with a glance that said, I cannot imagine to what you are referring.

Time passed. Our children grew up and went off to college. I left my job at Colby College in Maine and joined the faculty at Barnard. My mother died at age ninety-four. The mirror, which had reflected a young mom when Indigo first barged through the door, now showed a woman in late middle age. I had surgery for cataracts. I began to lose my hearing. We all turned gray: me, my spouse, the dogs.

That summer, I took Indigo for one last walk. She was slow and unsteady on her paws. She looked up at me mournfully. You did say youd take care of me, when the time came, she said. You promised.

She died on an August afternoon, a tennis ball at her side.

Sometimes, in the weeks that followed, Id find myself searching for her, as if she might be sleeping in one of my childrens empty bedrooms. But she wasnt there.

What was it I was looking for, as I poked around the house? Was it really the dog Id lost? By the time youre in your fifties, a lot of things have flown. You learn to make your peace with ghosts, but its an uneasy truce, at best. Id sit in my childrens bedrooms now and again and get all mopey about the fact that theyd become adults so swiftly. Here were the talismans of their childhood: finger paintings from pre-K, an old soccer ball, college diplomas.

The rooms reminded me of a photograph Id once seen of the tomb of Tutankhamun, with the relics of the boy-kings lifea golden mask, an ancient checkerboardstrewn around the burial chamber. They lay where theyd been left, three thousand years before.

Id been their mother for seventeen years, but for years before that Id been a father, a boyfriend, a child. I had never regretted coming out as trans, living in the world without shame or secrets. But there were times when I remembered my younger self the way youd remember a dear friend youd lost, for reasons you no longer quite understood. Where was that boy, that adorable nerd whod spent his days sitting on the banks of a stream in Pennsylvania, fishing for brook trout? I wondered, sometimes, what had become of him. Would it be necessary, in the days to come, to refer to him only in scare quotes?

My days have been numbered in dogs. Even now, when I try to take the measure of the people I have been, I count the years by the dogs I owned in each season. When I was a boy, for instance, I had a dalmatian named Playboy, a resentful hoodlum who loved no one except my father. Later, as a hippie teenager, I had another dalmatian, a mournful, swollen creature named Sausage. While I was off at Wesleyan becoming insufferably cool, my sister brought a mutt named Matt home from Carleton, a dog whose insatiable sex drive and accompanying disregard for the rule of law made it abundantly clear that he was determined, as they say in Ireland, to live a life given over totally to pleasure. Still later, during my years as a nascent hipster in New York, my family acquired a Lab named Brown whose only true devotion was to eating her own paws, a pastime that obsessed the dog as if her feet were a rarity more succulent than clams casino. In my thirties, as a young husband, I adopted a Gordon setter named Alex, a wise soul who stood watch over my wife and me right up until the day our first child was born. And then, as a father, I shared a house with Lucy, a retriever/chow chow mash-up who wasted exactly zero time in making clear her utter contemptfor me, for our children, for all of us. Wed come home each day to find the dog in a state of cynicism and disapproval. Ohh, shed say, just like Tony Sopranos mother. Look who calls.

It was Lucy who was on duty the day I finally came down the stairs in heels. She looked me up and down with exhaustion. Ugh, she said. I wish the Lord would take me now.

Actually, a lot of people reacted like that at first, including many of the men and women I had loved most.

When we talk about dogs, it is not uncommon for people to say things like They love us unconditionally! Their hearts are so pure! But to be honest, I have rarely found this to be the case. When I was a boy, for instance, there was a German shepherd named Gomer who lived on a farm near our house. Most of his days were spent at the end of a heavy iron chain. If hed been given the option, it was clear enough: Gomer would have torn me apart like a Walmart piata. The only thing unconditional about Gomers feelings toward me was his bottomless hate.