Table of Contents

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Copyright 2018 by George Zebrowski.

All rights reserved.

Published by Wildside Press LLC.

wildsidepress.com

Edited by Pamela Sargent

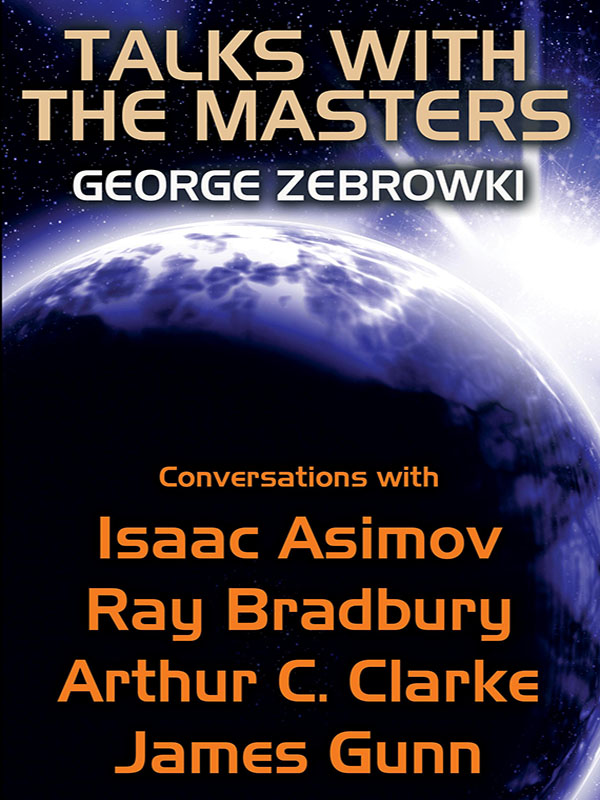

Isaac Asimov: The Last Interview is copyright 1991, 1992, 1993, 1994 by George Zebrowski. A slightly different version of this interview was published in Science Fiction Review , Vol. 2, No. 5, December 1991. This version, first published in Foundations Friends (Revised and Expanded Edition), edited by Martin H. Greenberg (Tor, 1997), is a slight revision from the one reprinted in Nebula Awards 27 , edited by James Morrow (Harcourt Brace, 1993).

Ray Bradbury: Ray Bradbury, Looking Back on a Lifetime of Science Fiction, Says that for Better or Worse, the Future Is Now, Sci Fi Weekly , June 21, 2004; reprinted in Synergy SF: New Science Fiction , edited by George Zebrowski (Five Star, 2004). Copyright 2004 by George Zebrowski.

Arthur C. Clarke: Arthur C. Clarke Interviewed by George Zebrowski, Sentinels in Honor of Arthur C. Clarke , edited by Gregory Benford and George Zebrowski (Hadley Rille Books, 2010). Copyright 2010 by George Zebrowski.

James Gunn: Interview with James Gunn appears here for the first time.

Photo of Isaac Asimov and George Zebrowski copyright 1991 by Jay Kay Klein.

ALSO BY GEORGE ZEBROWSKI

Black Pockets and Other Dark Thoughts (short stories)

Brute Orbits

Cave of Stars

Empties

In the Distance, and Ahead in Time (short stories)

The Killing Star (with Charles Pellegrino)

Macrolife

The Monadic Universe (short stories)

Stranger Suns

Swift Thoughts (short stories)

THE OMEGA POINT TRILOGY

Ashes and Stars

The Omega Point

Mirror of Minds

STAR TREK NOVELS

A Fury Scorned (with Pamela Sargent)

Heart of the Sun (with Pamela Sargent)

Dyson Sphere (with Charles Pellegrino)

Across the Universe (with Pamela Sargent)

Garth of Izar (with Pamela Sargent)

THE SUNSPACER TRILOGY

Sunspacer

The Stars Will Speak

Behind the Stars

INTRODUCTION, by Pamela Sargent

George Zebrowski and I were college freshmen when we met, still in our teens, but George already knew that he was going to be a writer. Specifically, he wanted to be a science fiction writer. I was an aspiring writer myself, but had only a vague idea of how to go about becoming one. George, however, had actually met some of the writers he so admired, including such luminaries as Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov, whose example and encouragement inspired him to achieve his ambition. Much later, after more than three decades of being a professional science fiction writer himself, George interviewed four of the authors whose work and whose example had inspired him.

Or, as George puts it, I encountered the gods of my youth as a colleague. This book is the result of those encounters.

* * * *

Isaac Asimov was born on January 2, 1920, in Petrovichi, Russia. He immigrated with his family to the United States as a toddler, grew up in Brooklyn, New York, and became a biochemistry professor at the Boston University School of Medicine while pursuing writing. A prolific writer who published nearly five hundred books, he was the author of the science fiction classics I, Robot, the Foundation trilogy, The Caves of Steel , The Naked Sun , and the Nebula and Hugo Award-winning The Gods Themselves. He also published nonfiction on a wide variety of subjects, among them astronomy, biology, math, religion and literary biography. (George claims that it was Isaacs The Intelligent Mans Guide to Science , later revised as Asimovs Guide to Science , that helped get him through the dreaded New York State Regents science exams in high school.) Asimov died in New York City on April 6, 1992.

Like Asimov, George was also an immigrant to the U.S., arriving with his parents in the early 1950s and growing up in New York City (Manhattan and the Bronx, his residence in those two boroughs separated by a year and a half in Miami, Florida). About his first meeting with this writer whom hed been reading for years, he writes:

I first met Isaac Asimov at the World Science Fiction Convention of 1963, held in Washington, D.C. I had seen him at various gatherings since 1960, but had not had the courage to approach him. Now, not quite eighteen, I was so overwhelmed by my recent reading of the Foundation trilogy that I stumbled over my words as I shook his hand.

Er, wouldyou ask me a question? I asked, inadvertently baring the ego of a would-be writer.

Of course! he shouted at once, delighted by the opening I had given him. What would you like me to ask you ?

I went red and my knees shook, and he seemed to enjoy my consternation mightily. I had expected to meet the austere Hari Seldon and to feel the exhilaration of reason that was for me the great distinguishing feature of Asimovs work: I had not expected to meet an ebullient Hari Seldon. A moment passed. I felt relieved, and a bit flustered, when Isaacs knowing smile turned into a kindly gaze.

In the years to follow, George, often with me tagging along, spent time with Isaac at various conventions and events, including the 1972 Nebula Awards Banquet held in New York City in the spring of 1973 (Berkeley, California and New Orleans, Louisiana were the sites of two other Nebula banquets that took place simultaneously), where Isaac won his first Nebula Award, given by the Science Fiction Writers of America (now the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America) for The Gods Themselves. Although he was honored earlier in 1963 with a special Hugo Award for his science essays in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction and another Hugo for Best All-Time Series for the Foundation trilogy in 1966, this was his first major SF award for a single work. We were with a small group who joined Isaac for drinks after the awards ceremony, which was, as George recalled, both a triumphant and melancholy event for the winner:

Isaac called to me from across the emptying banquet hall. Startled, I waited for him to approach.

This is itthe end, George, he said.

What do you mean? I replied.

He held up his award trophy. Ive reached the top,

Im sure youll win another, I said. My words did not seem to cheer him as he wandered away.

In time I learned what a quagmire human nature and humans are, but it still seems to me that we need the exhilaration of reason to cut through to better circumstances for our kind; I must confess that it saddens me how few of my fellow humans have this feeling for reason, but then even Hari Seldon must have had his despairing moments.

And as it happened, Isaac was still far from reaching the top. Ahead of him were having his books on the New York Times bestseller list, more Nebula and Hugo Awards, an asteroid named in his honor in 1981 (5020 Asimov), and a movie based on his award-winning novelette The Bicentennial Man starring Robin Williams, to name only a few of the high points.

In 1983, George collaborated with Isaac and prolific anthologist Martin H. Greenberg on a major anthology, Creations: The Quest for Origins in Story and Science (Crown, 1983). And in the late 1980s, George had the opportunity to write about one of his favorite Asimovian characters, Hari Seldon, when he was invited to contribute a story to Foundations Friends , an anthology in honor of Isaac Asimov with original stories using characters and settings created by Asimov. George remembers working on that story, Foundations Conscience, this way:

I discussed Foundations Conscience with Isaac by phone as I was writing it, and some interesting ideas came upone being that artificial intelligence, not sharing human evolution and psychology, would be free of Hari Seldons psychohistorical laws and might be able to strike out in new directions, perhaps according to psychohistorical laws of their own, with a relatively greater degree of freedom than humankind had ever had. Isaac seemed struck by this idea, and I imagined that it might play some role in the last Foundation book. I feel now that Isaac came by and asked me to come play in his backyard for a while. The pleasure and sureness I felt in writing Foundations Conscience reveal to me the pervasiveness of his influence on my early character and later writing life.