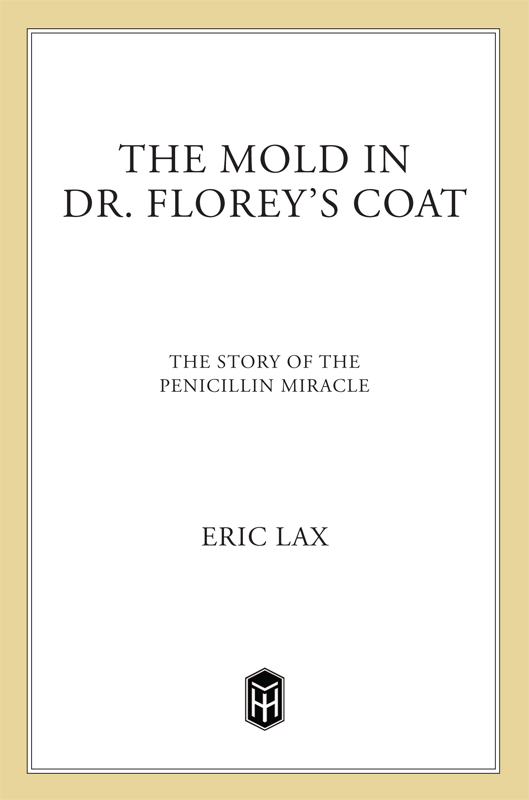

Eric Lax - The Mold in Dr. Floreys Coat: The Story of the Penicillin Miracle

Here you can read online Eric Lax - The Mold in Dr. Floreys Coat: The Story of the Penicillin Miracle full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2004, publisher: Henry Holt and Co., genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Mold in Dr. Floreys Coat: The Story of the Penicillin Miracle

- Author:

- Publisher:Henry Holt and Co.

- Genre:

- Year:2004

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Mold in Dr. Floreys Coat: The Story of the Penicillin Miracle: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Mold in Dr. Floreys Coat: The Story of the Penicillin Miracle" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Eric Lax: author's other books

Who wrote The Mold in Dr. Floreys Coat: The Story of the Penicillin Miracle? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Mold in Dr. Floreys Coat: The Story of the Penicillin Miracle — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Mold in Dr. Floreys Coat: The Story of the Penicillin Miracle" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

For my son John

The more intelligent the question you ask of Mother Nature, the more intelligent will be her reply.

SIR CHARLES SHERRINGTON

On March 14, 1942, thirty-three-year-old Anne Miller lay in New Haven Hospital dying of blood poisoning. She had developed a bacterial infection following a miscarriage a month before, a then common complication that quickly could turn fatal. For all those weeks her temperature swung between 103 and 106 degrees F (39.4 and 41.1 degrees C), often leaving her delirious as her condition worsened and her body wasted away from her inability to eat. Blood transfusions, surgery, and many doses of the recently developed sulfa drugs all failed to kill the streptococcus that had colonized her blood.

Her doctor, John Bumstead of the Yale clinical faculty, was about out of hope for her when he remembered a passing conversation with Dr. John Fulton, another of his patients, who was lying ill in a nearby room. Fulton and his wife were friends of Howard Florey, an Oxford University scientist who headed the group that was developing an almost unknown substance called penicillin, which was many times more powerful against bacteria than any known drug. The devastation and the crippling of industry caused by World War II made further production and testing in England difficult, so in 1941 Florey and his colleague Norman Heatley had come to the United States to try to persuade American drug companies to work on this potentially miraculous but still unproven medicine. Heatley had even stayed on to help the New Jersey pharmaceutical company Merck manufacture penicillin.

Bumstead beseeched Fulton to help him get some of the drug for Mrs. Miller. Fulton, a champion of Floreys research, knew the chairman of the Committee on Chemotherapy in Washington, D.C., which controlled all important medicines during World War II; after Fultons call he authorized Merck to release 5.5 g of penicillinabout a teaspoonful. It was half of the entire amount in the United States.

The tiny cache of raw antibiotic was soon delivered to Mrs. Millers room, where it was passed through an extrafine filter to remove impurities and dissolved in a saline solution. No one was certain of the appropriate dose, so a small one was injected by an intern, at three P.M.

Her doctors waited for a possible adverse reaction, but when after four hours there was none, a larger dose was administered. When the second dose also caused no harmful reaction, all other medication was discontinued and penicillin was injected every four hours. By midnight her temperature was down to 100 degrees. By nine A.M. the next day, it was normal for the first time in a month. She began to eat hearty meals, again for the first time in weeks. Within twenty-four hours, the deadly bacterial growth in her blood had disappeared. After a month-long convalescence, during which Mrs. Miller received more penicillin manufactured by Merck, she went home and lived a pleasant life until she died in 1999, at age ninety.

Four patients in Oxford had been cured by penicillin several months earlier, but Anne Miller was arguably the first patient pulled back from deaths door by the drug. Her reclaimed life marks a revolution in medicine that has touched virtually everyone on Earth.

* * *

In the fifth century B.C. , Herodotus noted in his History that every Babylonian was an amateur physician, because the sick were laid out in the street so that any passerby might offer advice for a cure. For the next twenty-four hundred years that was as good an approach to infection as any, since all doctors remedies against it were almost uniformly powerless. Until the middle of the twentieth century, mothers often died from infections following childbirth; children succumbed to diarrhea, scarlet fever, and complications of tonsillitis; and anyone who survived other onslaughts often was taken by pneumonia or meningitis. Soldiers most commonly died not from war injuries but from resulting infections such as septicemia and gangrene. Away from the battlefield, boils, abscesses, and carbuncles were common portals for life-threatening illness; the smallest cut could lead to a fatal infection. For much of human history, sex brought painful aftereffects in gonorrhea and eventually death in syphilis. There were a few antidotes to infection: vaccination against smallpox with cowpox vaccine, first done in 1796; the introduction of antiseptics in 1865; and the advent of sulfa drugs in 1935. Yet arrayed against these were the menacing presences of scarlet fever, typhoid fever, rheumatic fever, tuberculosis, cholera, plague, typhus, dysentery, and a catalogue of other diseases for which the doctors best treatment was a soothing bedside manner and a steady dose of optimism; skillfully administered, this lasted the patients until they died.

All this changed in 1940, when Howard Florey, Ernst Chain, Norman Heatley, and fewer than a half-dozen others at Oxford produced penicillin. They performed their work on a minuscule budget with makeshift equipment during the most perilous time for England in World War II. The imminent possibility that the Nazis would invade the country meant that the scientists might have to destroy their work on a few hours notice to keep it from enemy hands, and they hatched a brilliantly simple plan in the event that happened. With the hope that at least one of the team would be able to find refuge and continue the work on Penicillium notatum, the particular mold that spawned penicillin, Florey and four of his colleagues rubbed some of its spores in their clothes. Spores are hearty stuff, and, if necessary, those Penicillium spores could lie undetected and dormant for years and then be revived for further study. The invasion, of course, never occurred. Within two years they had something other than optimism for doctors to administer to their patients.

* * *

The development of penicillin was the culmination of advances large and small that began in biblical times. Just what caused infection was so unclear for millennia that a common explanation was simply to attribute epidemics to the wrath of the gods. Hippocrates, the Greek physician born in 460 B.C. and famous for the oath taken by new doctors to first do no harm, made a step toward understanding in his book Airs, Waters and Places, which detailed his observations of the relation between physical influences and illness. The Book of Leviticus (14:3353) specifically details how to segregate lepers to avoid contact with them; careful observers had noticed that diseases could be passed from one person to another not only through physical contact but also by items used in common, such as utensils and clothing.

The first person to see and identify a microbe was Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, a Dutch draper and lens grinder. In 1675, he invented the microscope, a magnifying glass attached to a three-inch-long piece of brass. Even with so primitive an instrument, Leeuwenhoek saw moving objects in a drop of his own saliva, which left him reeling from the notion that these things were in his body. Because the objects moved, he presumed they were alive, and he wrote of them as little animals, a thousand times smaller than the eye of a full-grown louse.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Mold in Dr. Floreys Coat: The Story of the Penicillin Miracle»

Look at similar books to The Mold in Dr. Floreys Coat: The Story of the Penicillin Miracle. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Mold in Dr. Floreys Coat: The Story of the Penicillin Miracle and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.