First photo insert:

Photos of Susan Blow, courtesy of Carondelet Historical Society.

Second photo insert:

Freud family at Jacob Freuds grave, courtesy of the Freud Museum, London.

View of the Allgemeines Krankenhaus (General Hospital), ca. 1895, Michael Huey and Christian Witt-Drring Photo Archive.

Freuds study, courtesy of Susannah Stone.

Emperor Karl and Empress Zita at the funeral of Emperor Francis Joseph I, November 1916; Vera Sacrum cover, January 1898, and Cabaret Fledermaus program cover, 2nd issue, 1907, all Michael Huey and Christian Witt-Drring

Photo Archive.

Copyright 2006 George Prochnik

Production Editor: Mira S. Park

eISBN: 978-1-59051-621-8

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from Other Press LLC, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. For information write to Other Press LLC, 2 Park Avenue, 24th Floor, New York, NY 10016. Or visit our Web site: www.otherpress.com.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

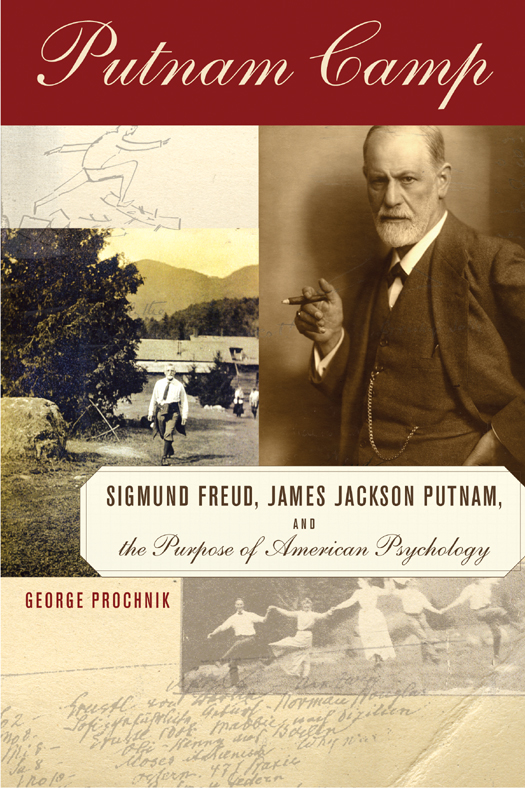

Prochnik, George.

Putnam camp : Sigmund Freud, James Jackson Putnam and the purpose of psychology / by George Prochnik.

p.; cm.

1. Freud, Sigmund, 18561939Friends and associates. 2. Putnam, James Jackson, 18461918. 3. PsychoanalysisHistory.

[DNLM: 1. Freud, Sigmund, 18561939. 2. Putnam, James Jackson, 18461918. 3. Psychoanalysishistory. 4. Freudian Theoryhistory.

WM 11.1 P963m 2006] I. Title.

BF109.F74P76 2006

150.19520922dc22

2005034312

v3.1

For my parents,

Marian and Martin Prochnik

Contents

Introduction

W OULD S IGMUND F REUD have been able to make sense of America today? Would James Jackson Putnam have been able to hold onto his unbounded idealistic faith in the inevitable progress of civilization had he been confronted with a typical nights roster of pop culture entertainment? Above all, do Freud and Putnam and the conversation they carried on hold lessons for us today, at a moment when self-reflection is often impugned as self-indulgence, a sign of weakness or, at the least, a practice meant to be confined to our houses of worship and private prayers?

The suburb of Washington DC in which I spent my wonder years could have been Disneyland for the psychoanalytically inclined. It wasnt only a matter of the pale, hollow-eyed father of my dear friend Francesca with his twitchy, penciled moustache, who lived down the street from us and was found to have been raping Francesca and her older sister for over a decade before a police car arrived to coast him silently away; or the stiff Vietnam vet dad who flushed into mulberry rages whenever he heard a helicopter overhead; or poor, lovely Mrs. Freid who cut my familys hair while her two blonde, cereal-commercial children played about her legs until she became convinced that a spy plane was watching her, relentlessly watching her, so that she had to fly away from everyone; or Mr. Fells, who played Uncle Sam every year in our Fourth of July parade because he looked the spitting image of the recruitment poster icon, and yet was finally driven out of town for squeezing babysitters and reveling in supermarket kleptomania at the local Safeway. Beyond these standouts, within a mile radius of our little brick tract house on its quarter acre moat, there were opportunistic pedophiles, a flasher who dressed in a bunny suit, one father murderer, drug abusers and vandals galore, animal torturers, arsonists, and wild-eyed emaciated Christian Scientists who refused to give money to UNICEF because the money kept communist children alive.

It would be comforting to think that incidences of mental malfeasance in my home suburb were disproportionate to the national mean. I am, alas, unconvinced that our little mall-bound settlement exceeded the volume of psychological stigmata of any American community priding itself as ours did on its safety, wholesomeness, and shopping. This raises the question of what does nourish mental well-being in our culture.

O VER TIME , I VE wondered more about whether the lurid sexual, sadistic, and just plain crackpot behaviors festering behind the pasteboard doors of my suburb could in fact be fit into any classic psychoanalytic paradigm. Freud remarked in more than one place that repression was the core concept of psychoanalysis. Was repression truly a relevant idea in trying to comprehend this neighborhood? Somehow, the inhabitants of my suburb managed to be simultaneously repressed and all too virulently manifest. Not infrequently, people were repressed until the moment they crossed the linoleum threshold of their basements. Then all hell broke loose. As though our suburban homes were modeled on Freuds fanciful topography of the mind, with the basement playing Id, the living room, Ego, while the bedrooms werewhat? Beyond the pleasure principle?

Its not, of course, the case that these kinds of questions bothered me in the years I was growing up. At the time, my concerns were largely, selfishly, confined to a riff on the gnostic doxology: How did I get here? What am I doing here? And, how the hell can I get far away?

My fathers family had fled Austria in 1938. From a privileged world of comfortable apartments in the 3rd District, where family members worked as physicians, psychoanalysts, opera singers, cantors, and scientists, taking their pleasure in Viennas palaces of culture, in Alpine summer chateaux, and inside Opel Olympias orbiting the Ringstrasse, my father found himself washed up in a Hells Kitchen tenement and on the verge of starvation. The Jewish welfare society that kept his family from perishing encouraged them to move to Boston where there waited a subsidized apartment and an English language program that could help my grandfather train for his American medical license. In Vienna, he had been a prominent general practitioner with an illustrious clientele, including the high-ranking Nazi official who warned him that they were on the list to be transported within twenty-four hours. He was already in his sixties by the time he arrived in America, and though he managed to learn English well enough to rebuild a practice focused in gynecology and become a respected diagnosticianwith a loyal share of female clientele soliciting from him something akin to psychological treatmenthis practice never did well enough to enable the family to approach the lifestyle theyd enjoyed in Europe.

Still, my grandfather got his two sons into Boston Latin School and Harvard. It was while my father was in Cambridge studying geology that he met my mother, who was then teaching at the Shady Hill School, a progressive learning environment with a density of analyst offspring so great that one can only speculate how many teachers ended up prostrate on the couch themselves.

My mothers experience of America could not have been more antithetical to my fathers. Born at Bostons renowned Lying-in Hospital (where every day is labor day), she was descended on her own mothers side from Cabots, Putnams, Lowells, Higginsons, Mathers, Cottons, Hutchinsons, and many of the other high-minded families that made up the insular, indeed ingrown, world of Bostons chosen families. Her father, a surgeon, was the first of a clan of impoverished Scottish immigrant tobacco farmers scattered across the Carolinas to break ranks and head north, in his case to Harvard Medical School. Once there, excepting his fondness for breakfasting on scrapple and grits, he washed away his southern heritage like so much red clay.