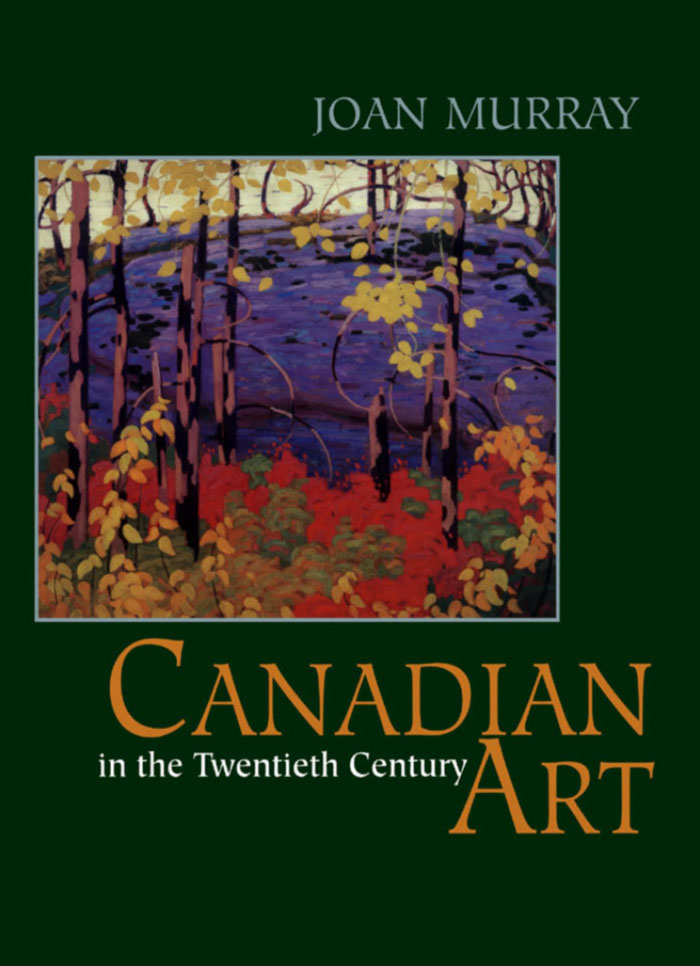

CANADIAN

ART

in the

Twentieth

Century

Joan Murray

Fig. 116. Rita Letendre (b. 1929) Retrovision, 1961 Oil on canvas, 45.7 x 50.8 cm Private Collection

Joan Murray

C ANADIAN A RT

in the Twentieth Century

Copyright Joan Murray 1999

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (except for brief passages for purposes of review) without the prior permission of Dundurn Press. Permission to photocopy should be requested from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency.

Editor: Sarah Bowser

Design: V. John Lee

Printer: Transcontinental Printing Inc.

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data

Murray, Joan

Canadian art in the twentieth century

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-55002-332-2

1. Painting, Canadian. 2. Painting, Modern 20th century Canada History. I. Title.

ND245.M855 1999 759.II C99-932166-8

1 2 3 4 5 03 02 01 00 99

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the support of the Ontario Arts Council and we acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP) for our publishing activities.

Care has been taken to trace the ownership of copyright material used in this book. The author and the publisher welcome any information enabling them to rectify any references or credit in subsequent editions.

J. Kirk Howard, President

Printed and bound in Canada.

Printed on recycled paper.

Printed on recycled paper.

Dundurn Press

8 Market Street

Suite 200

Toronto, Ontario, Canada

M5E 1M6

Dundurn Press

73 Lime Walk

Headington, Oxford,

England

0X3 7AD

Dundurn Press

2250 Military Road

Tonawanda NY

U.S.A. 14150

Table of Contents

Fig. 1. Landon Mackenzie (b. 1954) Canoe/Woman, 1987-1988 Acrylic on canvas, 152.4 x 182.9 cm (approx.) Private Collection

Introduction

Place is the dominant feature of civilizations, writes John Ralston Saul in Reflections of a Siamese Twin (1997). A great deal of culture is born from sharing a place. It determines what people can do, how they live and create their culture. Saul believes that place takes on a conscious importance for people who live on the geographic margins as we do in Canada. In this country, we have an English-speaking empire and a French-speaking empire. The art created by the two groups interacts. That the United States is next door creates an intense nearby cultural presence. Mexico, too, has its influence.

Time is the crucial factor in our sense of place: it is the quality without which we cannot experience anything. Canadian art has its own time and place, its own fabric and texture. Has it its own favourite national symbols? The beaver, the maple leaf, the canoe? None of these is really national in the sense of being pervasively present across the country; none carries the country along with it as a whole. Take the canoe, for instance. In the exhibition In the Wilds, at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg in 1998, curator Liz Wylie focused on the canoe as a symbol or clich that has permeated Canadian culture and art. However, the undecked, bark-covered boat, the model for todays typical Canadian canoe, was a regional variant. In that respect, as writer John Barber has suggested, the Canadian canoe is exactly like the maple leaf, which comes from a tree that, west of Ontario, is either rare and shrubby or unknown.

Even the word canoe is not from a North American aboriginal language; it comes from the Caribbean Arawak and means boat. It is a symbol that, like the beaver and maple leaf, acts as a link between Canadian art and the wilderness, which, for many, is the significant aspect of Canadian art.

You dont have to read Canadian literature or history to understand the allure of the environment. Anyone who has ever stepped outside his front door knows that this is a part of Canada that will not, we hope, degrade and change. In art, the aura, the authentic atmosphere around the original may vanish; the image of a specific place, time, and season endures.

Environments are not passive wrappings, but are, rather, active processes which are invisible, wrote Marshall McLuhan. Art reflects the environment in which it is made but as art is made, it alters us and future art. Tom Thomson painted Algonquin Park, thereby providing a template for future nature painters, but in the process of seeing Algonquin Park through his images, Canadians come to understand nature in a different way, a way which in time forms its own myth. To understand this process, it is necessary to understand not only the place art holds in the nations values, but the way artists maintain and pass on their beliefs. Each work of art is not only a study of style changes and techniques; it is also a manylayered meditation on the vicissitudes and pleasures of the environment. Beyond doubt, the accepted myth of our environment is in some measure the creation of our artists. It is also, now, part of our history.

Many twentieth-century histories of world art begin with Picassos Demoiselles dAvignon, conceived in 1906 and finished (some would say abandoned) during the succeeding year. In music, Arnold Schoenberg, the Austrian-born composer, had by 1909 arrived at atonality; in 1923, he introduced to the world his method of composing with twelve notes. I locate the beginning of Canadian art in the twentieth century with an account of the changes wrought by Post-Impressionism.

In 1929, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, curator Alfred Barr, in a memorable image, described the progress of art as a torpedo: the tail of the torpedo is contemporary art; its forward flight creates the new definitions of future art. What artists seek out defines where the century begins its art. In Canada, we look to the achievement of individuals such as Thomson, but Thomsons work grew out of a distinctive art movement: Post-Impressionism, spearheaded in Canada by four great pioneers: James Wilson Morrice, John Lyman, David Milne, and Lawren Harris. For these individuals, picture-making was the main subject, a way of working that defines the modern period.

For these artists, the heroes were the formal innovators among the European Post-Impressionists, among them Paul Czanne, who wished to make of Impressionism something solid and enduring, like the art of the museums. Czanne, Gauguin, and van Gogh provided a model of artistic freedom to North Americans, a way of expressing their personal vision. Post-Impressionism, which expanded upon qualities of colour, simplifying form, and creating a cohesive structure, was the initial phase of modern art in Canada.

Printed on recycled paper.

Printed on recycled paper.