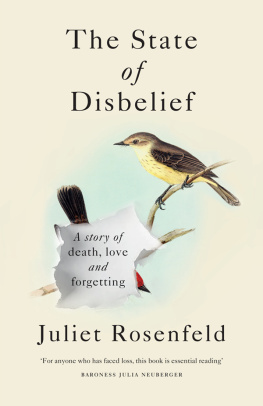

Juliet Rosenfeld - The State of Disbelief: A Story of Death, Love and Forgetting

Here you can read online Juliet Rosenfeld - The State of Disbelief: A Story of Death, Love and Forgetting full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Short Books Ltd, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The State of Disbelief: A Story of Death, Love and Forgetting

- Author:

- Publisher:Short Books Ltd

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The State of Disbelief: A Story of Death, Love and Forgetting: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The State of Disbelief: A Story of Death, Love and Forgetting" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The State of Disbelief: A Story of Death, Love and Forgetting — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The State of Disbelief: A Story of Death, Love and Forgetting" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Juliet Rosenfeld

To protect the privacy of others, some names and events have been changed, characters composited and incidents condensed.

AIR 27.04.62 08.02.15

We are never so defenceless against suffering as when we love, never so forlornly unhappy as when we have lost our love object or its love.

Mourning and Melancholia

Sigmund Freud, 1917

I am a psychotherapist and a widow. I experienced a brutal bereavement five years ago which devastated me and changed the course of my life completely. My husband Andrew, aged 51, a handsome, confident businessman, was diagnosed with lung cancer in an airless room high above the Marylebone Road on the Thursday before Christmas Eve, 2013. He had never smoked a cigarette. There was a dark view of skeleton treetops in Regents Park, and the evening rushhour traffic filed past determinedly as we were told the news by a locum GP, who we had met five minutes beforehand.

He died on 8th February 2015.

His sudden and unexpected death affected many people, terribly, in different ways; his parents, his adored first family. The only story of bereavement anyone can tell is their own, and no one can guess how a death made another person feel. This is only my story. But Andrew was a deeply loved son, brother and father, who lived for his four children.

Just as there is no hierarchy of grief, so to generalise about the experience would be a mistake, for sudden bereavement at the closest of quarters offers only two guarantees firstly, it is idiosyncratic and secondly, completely unimaginable until it happens. My only conclusion is that who you are, and what you have already lived through, define your experience of bereavement.

As time passed I realised I had been left in the unusual position of having the tools to explore this experience through the framework of psychotherapy, psychoanalytic ideas and writing. I thought I would try to merge the clinical skills I have developed over the last decade treating patients in private practice and the NHS, alongside twelve years of five-times-a-week psychoanalysis, with an account of what close bereavement does to your mind. In our case, a terrifying illness appeared one day, out of the blue, and suddenly became terminal, resulting in Andrews death, fourteen months after diagnosis. I wanted to describe this traumatic loss from a personal perspective by using the theoretical training that I had long used clinically.

But the truth is also that I wrote, to begin with, because there was no other option, no other way of making sense of an overwhelming feeling of disbelief about what was happening.

The experience of bereavement has left me with a deep interest in grief and mourning. It took me a while to realise how different these two feelings are, and how helpful an understanding of that difference can be. I wanted to capture these states of mind, and try to explain them in a way that is potentially therapeutic.

Central to this book is a short paper published in 1917 by Sigmund Freud, the founding father of psychoanalysis and psychotherapy. I rediscovered my scribbled-on and folded photocopy of Mourning and Melancholia in the days after Andrew died, and it became a handmaid to my recovery. Poignantly, I found it in his bedside table. I wonder if he read it. I returned to it often, and kept it, talismanic, by my bed or on the desk in my consulting room.

Only seventeen pages long, Mourning and Melancholia was written as World War I raged in 1915, and remained unpublished for two years. It is, like much of Freuds work, clinically original and innovative, but there is more to it than that. When I reread it in those first weeks I was struck by how it spoke to me, a century after its publication, when nothing else made any sense. Freud set out to define an idea that had been greatly preoccupying him; the effect of loss on the mind. He identified two distinct effects of loss: depression, (then known as melancholia) and mourning, which I term bereavement and which he separated into two phases grief and mourning.

This crucial distinction is what helped me to understand my own feelings: the savage trauma of loss that occurs at the moment of death grief and the longer, unpredictable evolution of that loss into something that we call mourning. Think of this as the earthquake and the after-shocks. The first is a shattering, visible, sudden eruption, which leaves the landscape devastated. The latter phase is slower, less predictable but just as painful, with occasional flashes back to the original grief. Ultimately, however, the wreckage is gradually cleared. The original shape of the terrain is visible. But the landscape is never the same again.

So, this is an explanation and differentiation of grief and mourning. For they are fundamentally different emotions, the latter only reachable after the former in some way departs. This discrepancy, not usually acknowledged, is part of the problem that the bereaved encounter. Grief today is often erroneously considered, as interchangeable with mourning. Contrary to some theorists and writers, I do not believe one can work through grief, in the same way one can work through other complicated experiences. To suggest it is possible risks a grave misunderstanding of the experience of the bereaved person. Working through grief implies agency. Certainly in the consulting room (and outside it) the patient must work through the wished-for or unwished-for ending of a relationship, the loss of a job, a partners anger, a parents inadequacy, a bodily self-hatred, but not the grief brought on by a death. I had no role or part to play in Andrew contracting terminal cancer, and could take no responsibility for it (unlike, say, the ending of my first marriage, or my tendency to blame my parents or my feeling negatively judged by my analyst when I was late for a session). But grief is firmly in control and must be endured. If the conditions permit, it will find its own way elsewhere eventually while mourning feels like it will never quite leave home, but must be accommodated in some way, for ever.

Reminding myself of these differing states of mind kept me afloat in those early days, and reassured me that I might not descend into an unmanageable psychological breakdown.

Mourning and Melancholia is arguably Freuds finest work, moving between the conscious and unconscious consequences of loss in its many guises. Freuds genius was to recognise which symptoms are shared by the bereaved and the depressed. In essence, Freud states that in depression we do not often understand why we are depressed, as we do not know what has been lost, while in grief and mourning we know precisely what is gone. Yet this knowledge doesnt necessarily hasten the recovery.

My understanding of degrees of bereavement has grown greatly in the last five years, clinically, theoretically and of necessity personally. My grandparents died in their eighties, and a very close childhood friend was killed in a car crash during our teens. These experiences were so different my grandparents deaths sad but expected; the death of my sixteen-year-old friend shocking, and unbelievable for a while but before Andrew died, I dont think I had any idea what this closest type of bereavement would feel like.

Death is a ubiquitous life experience and yet we pretend it will not affect us until that choice is taken away. I wish we could, and believe we should talk more about death and bereavement, be more alive to it in life. After Andrews death, in a state of shock, I went back to work with my patients and functioned well enough, but still struggled to conceptualise what his death was doing to my mind. During this period I decided to give up my further psychoanalytic training and developed a mistrust of my analyst, indeed lost faith in the process of psychoanalysis to help me. For a while, my own long psychoanalysis became a casualty of my very resistant strain of grief. The five-sessions-a-week treatment fell down badly six months or so after Andrews death, and eventually ground to a standstill a year later, ten years into it. Generalisation is the antithesis of psychoanalytic thinking but I would not prescribe five-times-a-week analysis on the couch to my freshly bereaved self again. I would not wish my demanding, rigid first analyst on my shell-shocked self again, but who knows how it might have worked for someone else? Analysis is a most individual experience. I respect his earlier work with me and I have much to thank him for. I am still an admirer and exponent of psychoanalysis, not a critic, but I also believe that where possible telling the truth is fundamental to the discipline and the truth is that psychoanalysis for grief did not work for me.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The State of Disbelief: A Story of Death, Love and Forgetting»

Look at similar books to The State of Disbelief: A Story of Death, Love and Forgetting. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The State of Disbelief: A Story of Death, Love and Forgetting and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.