Contents

Guide

Page List

OTHER BOOKS BY ERIC K. WASHINGTON

Manhattanville: Old Heart of West Harlem

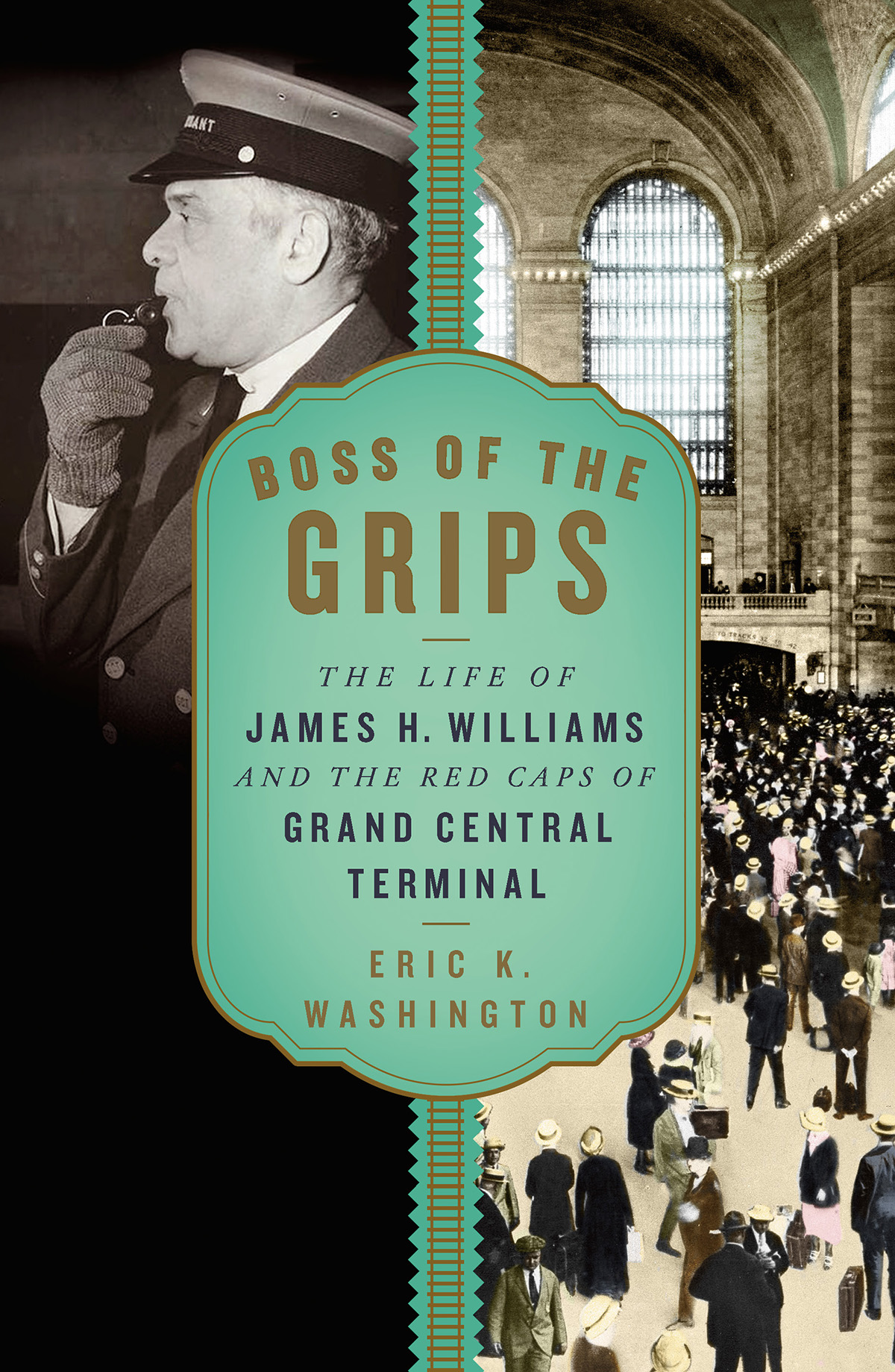

A sporty James H. Williams, seated with bowler hat.

No date, possibly 1910s. Schomburg/NYPL.

BOSS OF THE GRIPS

THE LIFE OF

JAMES H. WILLIAMS

AND THE RED CAPS OF

GRAND CENTRAL TERMINAL

ERIC K. WASHINGTON

FOR MY GRANDFATHER, JOHN MOSS, BORN IN 1843, AND FOR MY PARENTSALL OF THEM

At the Grand Central... is a colored man who probably knows more people than any other Negro in New York.

He is Chief James H. Williams, head of the Red Caps of the... station.

NEW YORK AGE, 1923

CONTENTS

New York Citys Grand Central Terminal is a rightly celebrated tour de force that has captivated the traveling public for more than a century. Opened on February 2, 1913, the worlds largest railroad station was built by the American firms Reed & Stem and Warren & Wetmore. It showcases a host of such artistic talents as Jules-Flix Coutan, whose monumental sculpture of Hercules, Mercury, and Minerva above a Tiffany clock crowns the buildings entry; and Paul Csar Helleu and Charles Basing, whose cerulean painted ceiling transports a mind-wandering traveler to the blue heavens. Many regarded it as the finest example of Beaux-Arts civic planning in New York, at once an architectural confection and a masterwork of innovative design and engineering. Yet the sublimeness of Grand Central Terminals Tennessee pink marble concourses, its cascading ramps and stairs and opulent shadows, belies its once-essential operating model: the servitude of African-American workers.

The servitude in this case was rooted in the American tradition of racial exploitation. Northerners might have comfortably regarded their territory as a historically enlightened refuge from the harsh segregation practices of the South, or of a bygone era. However, twentieth-century New York City had ample evidence of its own Jim Crow policiesnotably at Grand Central. The stations tightly run system deployed a singular corps of black men in red caps as baggage portersRed Caps, as they were popularly knownwho at times numbered in the several hundreds. Travelers routinely hailed one of the ubiquitous wearers of red caps and put the porter through his paces. Or a porter, seeing no gain in being invisible, readily volunteered himself to unburden a travelers grip. The nature of a porters work, the noted writer E. B. White observed in The New Yorker, tends to put him in a class with beasts of burden. Indeed, throughout the bustling concourses, a porters often backbreaking and demeaning labor was integral both to the stations functional efficiency and to its glamorous ambience. It was perhaps inevitable that Grand Centrals Red Cap porter system became the model for numerous railroad stations across the nation.

Made categorically identifiable both by their apparel and by their complexion, the black workforce at Grand Central embodied Americas color linethe laws, bylaws, amendments, and social attitudes that closed doors to blacks. His travels through Europe had convinced Frederick Douglass by the 1880s that racial prejudice was purely an American feeling and did not innately belong to the broader white race. In the United States, the color line was a deep-seated cultural contrivance that had festered for generations. It was a panoply of contradictions. At times one felt its prohibitions only intuitively, yet they were as palpable as a taut rope. It could be woven into the collective subconscious by social mores or by deliberate legislative acts. But blacks also found ways to circumvent and mitigate impasses created when whites erected the color line: they bent and reconfigured it into opportunities and positions of leverage. Such was the case at Grand Central, where the color line afforded black workers the means, proverbially speaking, to make a way out of no way.

Indeed, redcapping flourished as one of the most iconic service occupations of the last century. It originated at Grand Central Depot in 1895 with a dozen white staff but had become exclusively black by 1905. A source of pride, the job was coveted by, and almost invariably associated with, African-American men. Whereas educated whites shunned the work as too low in status, educated blacks recognized it as a rare and propitious employment option in an era of rigid racial barriers. At Grand Central, African-American college students undertook redcapping as a means to pay their way through school. The man who created this opportunity for securing a foothold toward professional and social advancement was James H. Williams, a singular individual whose history at Grand Central Terminal is steeped in urban legend and the mythology of the landmark we know today.

Born to formerly enslaved African-American parents in 1878, Williams broke the color line of Grand Centrals white Red Cap attendants in 1903. Upon Williamss hire, the former public reminder that attendants are not porters, to carry baggagebut rather were on hand to assist station passengersbegan taking on a new definition. Starting in 1909, Williams served as the chief attendant (or chief porter, or chief red cap) of Grand Central Terminalits first and most notable African-American officerand remained in that position until his death in 1948. In this capacity, he embodied a unique juncture between black and white America. His influential forty-five-year tenure made the monumental railroad station not only a gateway to Americas greatest city but, just as much, a gateway to the nations greatest African-American neighborhood: Harlem. For nearly half a century, Chief Williams supervised a staff of men who were relegated by dint of race to the lowest stratum of the stations workforce, though their role was integral to the railroad system. Like their rail-roaming kin, the sleeping car (or Pullman) porterswho were also African-Americanthe station-bound Red Caps were crucial to the Swiss-watch precision of the terminal and woven into the beguiling experience of early twentieth-century railroad travel.

Williamss life coincided with key periods in the evolving social and cultural world of African Americans living in the ever-changing metropolis of New York City. His experiences offer a window on postCivil War America and the heady optimism of the Reconstruction era, a period that obliged the Williams family and their kind to discover strategies to sidestep financial dependency and social stigmatization in order to achieve some form of self-reliance. We follow Williams as a race man: he was an active, if unassuming, agent of the early twentieth-century ideological cause of racial upliftwhich strove to quell white prejudice through black self-improvement in education, business, labor, civic interest, and the artsthat in the 1920s would fuel the New Negro movement and the Harlem Renaissance. And we follow him through two world wars, whose veterans from his earlier Red Cap workforce at Grand Central acquire greater resolve to surmount the racial bigotry on their home front.

CONTENTS

CONTENTS