First published in the United States of America by Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2015

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Henion, Leigh Ann.

Phenomenal : a hesitant adventurers search for wonder in the natural world / Leigh Ann Henion.

1. Henion, Leigh Ann. 2. Spiritual biography. 3. Women shamansBiography. I. Title.

PROLOGUE

A REPORT CAME OVER THE RADIO IN SWAHILI: SOMEONE HAD SPOTTED A cheetah and her cubs.

Wed have to drive fast to get there. Do you want to go? my guide David Barisa asked, breathlessly. David was in his thirties, but he had a certain youthful panache given his shaven head, gold-plated sunglasses, and street-savvy nubuck boots. I couldnt tell if his excitement was over the predator sighting or the excuse to speed.

Sure, I said.

Wed been watching the largest wildebeest herd Id seen in the Serengeti, roughly 10,000 animals grazing and shuffling their feet in migration. Each year, some 1.3 million wildebeest move full circle through Kenya and Tanzania, following rains. Theyre joined by zebra and gazelle, as well as a cast of hungry characters that lurk in the fray. And the drama of all thisas its taught in textbookswas transpiring before me.

In the distance, thousands of additional wildebeest were clumped on the horizon, moving like silt-colored rivers. Breezes brought the sweet, nostalgic smell of hay. We bounded across rutted roads while David reeled off names of the animal groupings wed seen over the past few days: clan of hyena, pack of wild dogs, pride of lions, herd of elephants.

So, what do you call a group of cheetah? I asked.

Theyre usually alone, David said, grinding a gear. But when I see them together, I just call them a family.

I had to ask because Im not a scientist. No, Im a part-time teacher and freelance writer, mother of a young child, wife of a carpenter. So what was Igrader of papers, changer of diapersdoing gallivanting around the Serengeti? Why had I left my husband and two-year-old son back home in the hills of southern Appalachia?

My answer might come across as insane, orat the very leastoverly dramatic.

But heres the truth: I was on an epic quest for wonder.

Id been chasing phenomena around the world for more than a year when I arrived in the Serengeti, and I still had many miles to go. But my inspiration had been sparked even before I became a mother, whenthree years before my sons birthI visited the overwintering site of the monarch butterfly in central Mexico. Before I accepted the magazine assignment that took me there, Id never even heard of the monarch migration, during which nearly the entire North American population comes to roost in a small swath of forest. But witnessing millions of butterflies swirling, dipping, and gliding over a single mountaintop gave me an actual glimpse of what I mean when I refer to myself as spiritual but not religious.

Andin difficult timesmemories of that experience sustained me.

I dont know that I suffered clinical postpartum depression when my son was born, but I began to empathize with the horror stories the condition can lead to. Inspired by butterflies, I had long ago dreamed up a list of other natural phenomena Id like to experience. But travel to far-flung lands? Once I had a baby, I considered myself lucky to make it to the grocery store before it was time for bed.

Still, I mused: Children have the capacity to marvel over simple things in natureleaves, twigs, pebbles. Couldnt exploring just a few of earths most dazzling natural phenomenasteeped as they are in science and mythologymake the world similarly new again, reawakening that sort of wonder within me? Drudgery, after all, has nothing to do with growing up if we do it right andbeyond tending to the acute physical needs of a childlittle to do with what it means to be a good parent.

Right?

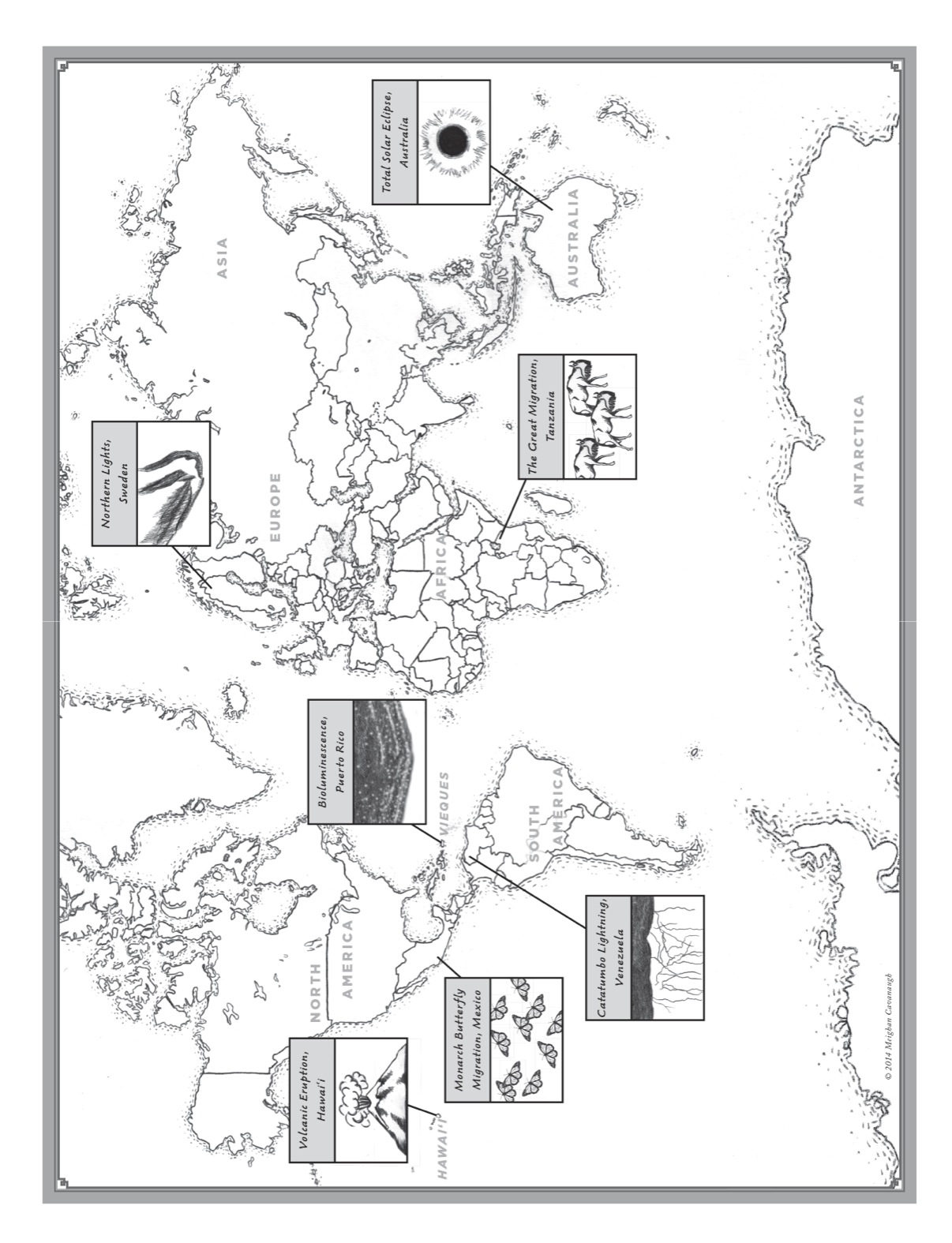

Back then, I didnt know that acting out my self-designed pilgrimage would put me in the path of modern-day shamans, reindeer herders, and astrophysicists. I had no idea there were lay people from all over the world, from all walks of life, already going to great lengths to undertake the sorts of phenomena chases Id dreamed up. Some took odd jobs to stay under the northern lights. Others left white-collar positions to make time for swimming in glowing, bioluminescent bays. These were people who braved pirates to witness everlasting lightning storms, stood on volcanoes, stared into solar eclipses. They trusted their instincts, followed their passions, willfully shaped their days into the lives they most wanted to lead.

And, somewhere along the way, I became one of them.

David pulled into a line of safari vehicles. The cheetah family consisted of a momma and three cubs. We stood in the pop-up roof of our Land Cruiser to see into the heart of their grassy nest. After a few minutes, the mother decided to rise. Her babies followed, in single file, and she crossed the dirt road to approach a wildebeest herd.

When they were still a ways out, the cubs took a seated position. Shes telling them to stay back, David said. The mother moved on. When she was just beyond the herd, she stopped to watch. Shes teaching them how to stalk, David reported. How to survive. Shes watching for a young wildebeest, the weakest of the herd.

The cubs were dark fuzz balls floating in a sea of grass. The mother cheetah stood taller. All her babies eyes were on her, watching. The light of day was beginning to fade. A giant elder wildebeest walked five feet in front of her. I gasped. Still, she waited.

He is too big for her, David said.