MICHEL EYQUEM DE MONTAIGNE (15331592) was born in Aquitaine, not far from Bordeaux, in the chteau of his wealthy aristocratic family. Educated by his father in Latin and Greek from an early age, Montaigne attended boarding school in Bordeaux before studying law in Toulouse. He then embarked on a distinguished public career, serving as a counselor of court in Prigueux and Bordeaux, becoming a courtier to Charles the IX, and receiving the collar of the Order of Saint Michael. After the death of his father in 1568, Montaigne succeeded to the title of Lord of Montaigne, and in 1571 he retired from public life in order to devote himself to reading and writing, publishing the first two volumes of his essays in 1580 and a third in 1588. From 1581 to 1585, he was the elected mayor of Bordeaux, confronting ongoing strife between Catholics and Protestants as well as an outbreak of the plague. Married to Franoise de Cassaigne, Montaigne was the father of six daughters, only one of whom survived into adulthood. He continued to write new essays and to add new material to the existing ones until the end of his life. The complete essays appeared posthumously in 1595.

JOHN FLORIO (15531625) was born in London, the son of Michelangelo Florio, a Tuscan convert to Protestantism who had moved to England because of his religious beliefs and who served as a language tutor to several highborn English families. Raised in Italian-speaking Switzerland and Germany, where his father fled after the Catholic Queen Mary I came to the English throne, John Florio returned to England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I and followed in his fathers footsteps as an instructor of languages, teaching French and Italian at Magdalen College, Oxford, and, under King James I, working as a private tutor to the Crown Prince and the Queen Consort. Florios works include First Fruits, which yield Familiar Speech, Merry Proverbs, Witty Sentences, and Golden Sayings; A Perfect Induction to the Italian and English Tongues; Second Fruits, to be gathered of Twelve Trees, of divers but delightsome Tastes to the Tongues of Italian and English men; Garden of Recreation, yielding six thousand Italian Proverbs; an ItalianEnglish dictionary, A World of Words (the second edition of which was entitled Queen Annas New World of Words); and his celebrated translation of Montaignes Essays.

STEPHEN GREENBLATT is the author of, among other books, Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare and The Swerve: How the World Became Modern (winner of the National Book Award, the James Russell Lowell Award, and the Pulitzer Prize). He is the John Cogan University Professor of the Humanities at Harvard.

PETER G. PLATT is a professor and chair of English at Barnard College. He is the author of Shakespeare and the Culture of Paradox (2009) and Reason Diminished: Shakespeare and the Marvelous (1997), and the editor of Wonders, Marvels, and Monsters in Early Modern Culture (1999). He has written articles about Shakespeare, Renaissance poetics and rhetoric, and John Florio. He is currently writing a book about Shakespeare and Montaigne.

SHAKESPEARES MONTAIGNE

The Florio Translation of the Essays

MICHEL DE MONTAIGNE

Translated from the French by

JOHN FLORIO

Edited and with an introduction by

STEPHEN GREENBLATT

Edited, modernized, and annotated by

PETER G. PLATT

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright 2014 by NYREV, Inc.

Introductory essays and notes copyright 2014 by Stephen Greenblatt and Peter G. Platt

All rights reserved.

Cover image: Hercules Segers, Three Books, c. 162030; Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Cover design: Katy Homans

The Library of Congress has cataloged the earlier printing as follows:

Montaigne, Michel de, 15331592.

[Essais. Selections. English]

Shakespeares Montaigne / by Michel de Montaigne ; translated by John Florio ; edited by Stephen Greenblatt and Peter Platt.

pages cm. (New York Review Books Classics)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-59017-722-8 (paperback)

I. Florio, John, 1553?1625, translator. II. Greenblatt, Stephen, 1943 III. Platt, Peter. IV. Title.

PQ1642.E6G74 2014

844'.3dc23

2013043477

ISBN 978-1-59017-734-1

v1.0

For a complete list of books in the NYRB Classics series, visit www.nyrb.com or write to: Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014.

Contents

Shakespeares Montaigne

1

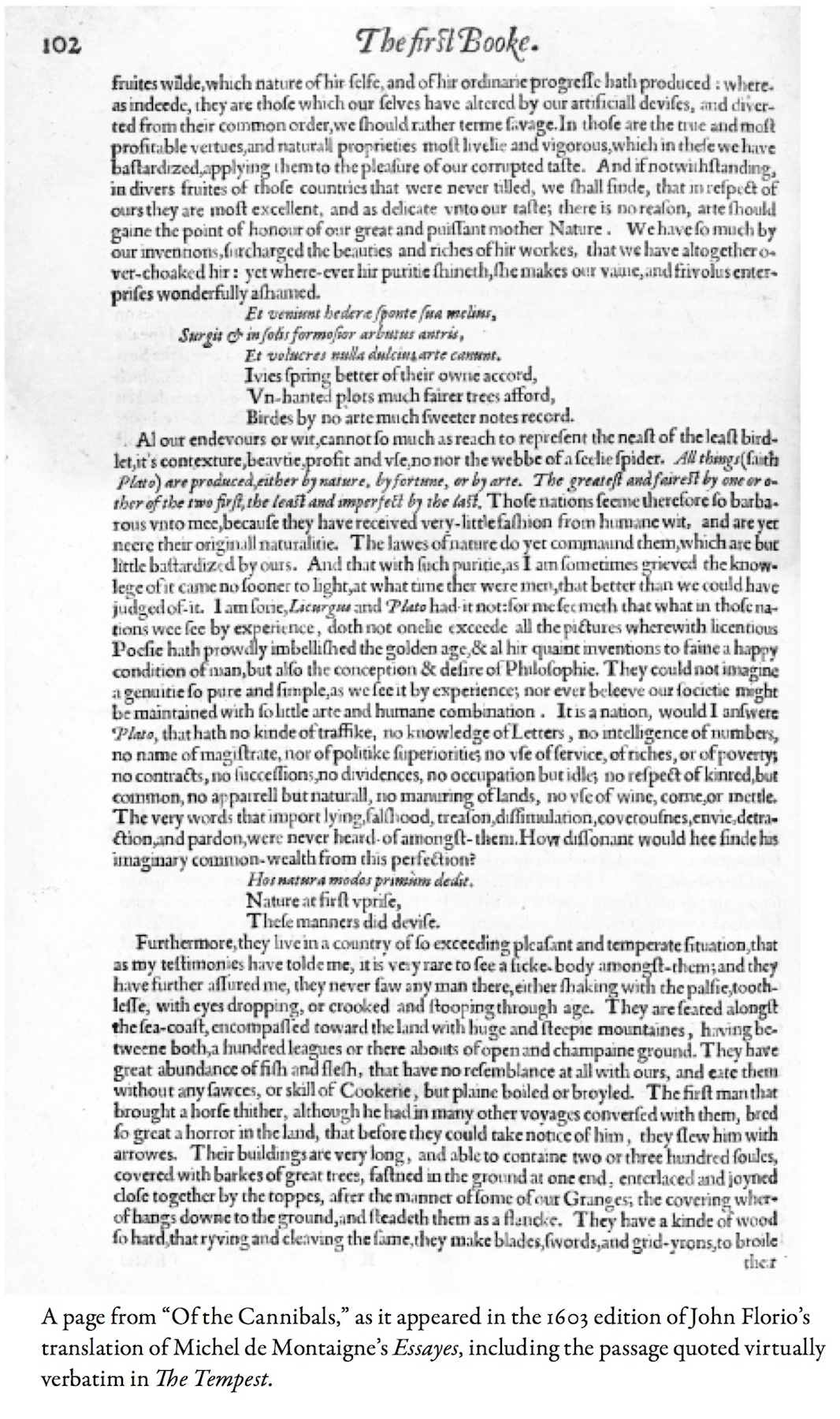

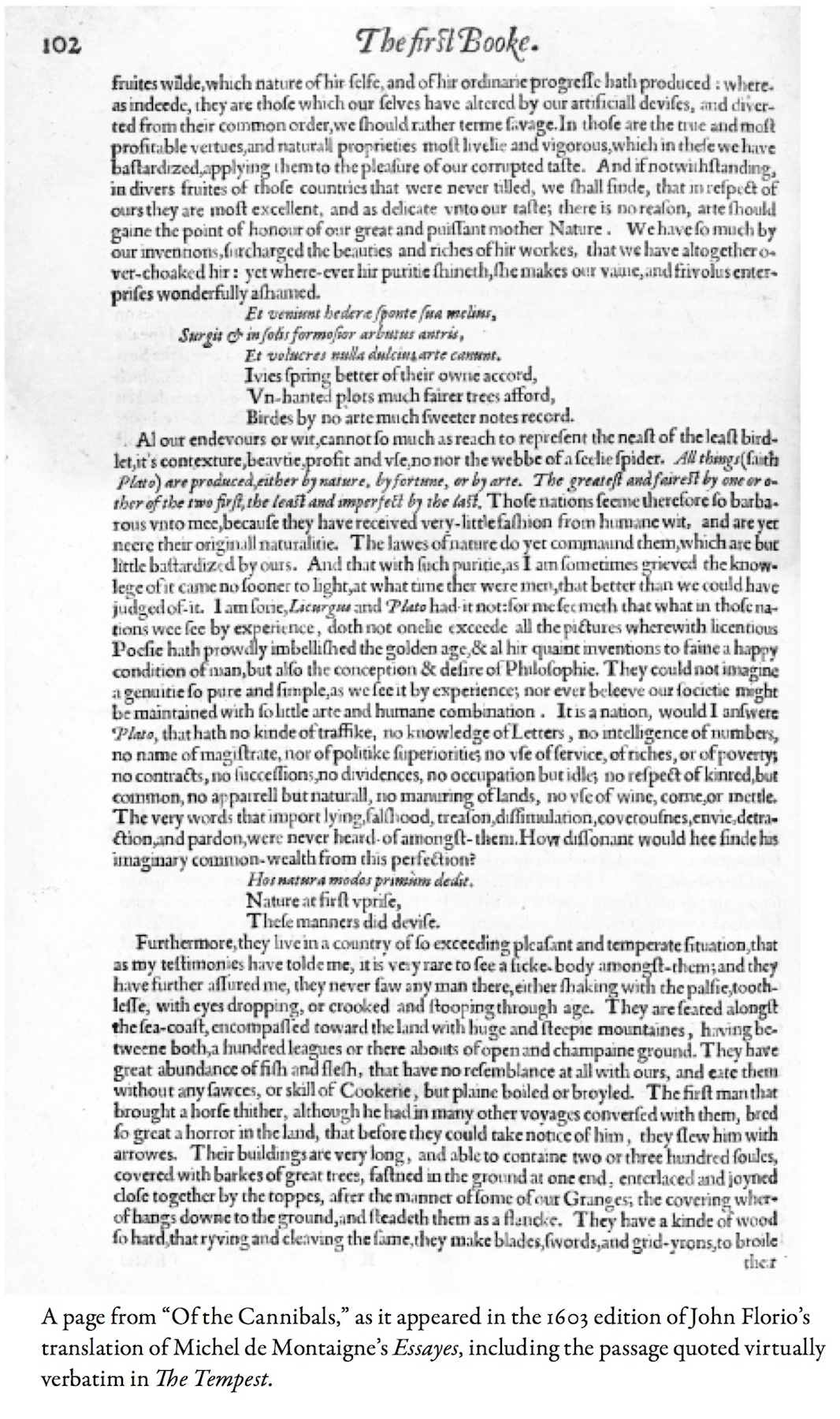

W HEN , near the end of his career, Shakespeare wrote The Tempest, the tragicomic romance that seems at least in retrospect to signal his impending retirement to Stratford, he had in his mind and quite possibly on his desk a book of Montaignes Essays. One of those essays, Of the Cannibals, has long been recognized as a source upon which Shakespeare was clearly drawing.

The playwright had long had some degree of acquaintance with French culture and language. For some time in and around 1604 he rented rooms in a house on Silver Street in London that belonged to a family of French HuguenotsProtestant refugees from religious persecution in their own country. Shakespeare probably already knew some French before he moved to Silver Street: He seems to have read in their original language several of the French sources he used in his plays, and Henry V (1599) includes a comical scene in which the French princess, instructed by her waiting gentlewoman, tries to learn the English words for the parts of the body: La main, de hand; les doigts, de fingres. Je pense que je suis la bonne colire; jai gagn deux mots danglais vitement. The scene ends with a flurry of dirty puns that depends on a familiarity with French obscenities.

Yet close attention to the allusions in The Tempest and elsewhere makes clear that Shakespeare read Montaigne not in French but in an English translation. That translation, published in a handsome folio edition in London in 1603, was by John Florio. For Shakespeareand not for Shakespeare alone but for virtually all of his English contemporariesMontaigne was Florios Montaigne. The essays selected here, in their rich Elizabethan idiom and wildly inventive turns of phrase, constitute the way Montaigne spoke to Renaissance England.

Shakespeare quite possibly knew Florio, who was twelve years his senior, personally. English-born, the son of Italian Protestant refugees, Florio was on friendly terms with such writers as Ben Jonson and Samuel Daniel. In the early 1590s, he was a tutor to the Earl of Southampton, the wealthy nobleman to whom Shakespeare dedicated two poems in 1593 and 1594. But it is not simply a likely personal connection that accounts for the fact that Shakespeare read Montaigne in Florios translation. The translation seemed to address English readers of Shakespeares time with unusual directness and intensity.

It is not that the translation was impeccably accurate. Montaignes French is often difficult and occasionally obscure, and there were many occasions in which the translator was venturing no more than an educated guess. But Florio was an exceptionally gifted linguist, steeped in Italian and French and at the same time in love with the resources of the English language. He had the great good fortune to be working at the moment when that language was at its most vital. The brilliance of his achievement was so generally acknowledged that even those English readers with very good command of FrenchJohn Donne, Walter Ralegh, Francis Bacon, and Robert Burton, to name a fewchose to encounter Montaigne through Florios English. To read the