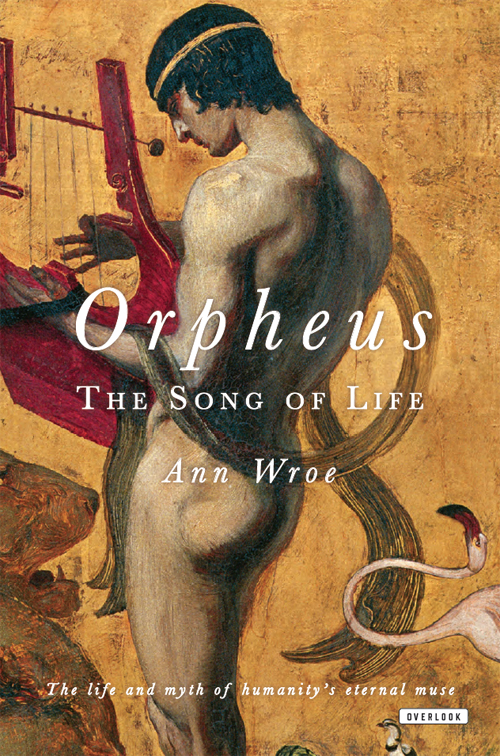

This edition first published in hardcover in the United States in 2012 by

The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

141 Wooster Street

New York, NY 10012

www.overlookpress.com

For bulk and special sales, please contact

Copyright Ann Wroe 2011

Eurydice from The Worlds Wife by Carol Ann Duffy. Copyright Carol Ann Duffy 1999.

Reproduced by permission of Picador, an imprint of Pan Macmillan Ltd Orpheus and Eurydice from New and Collected Poems by Czeslaw Milosz.

Copyright Czeslaw Milosz Royalties Inc. Reproduced by permission of Penguin Books The Man with the Blue Guitar from Collected Poems by Wallace Stevens.

Copyright The Estate of Wallace Stevens. Reproduced by permission of Faber and Faber Ltd Sue Hubbard is a poet, novelist and art critic.

Eurydice is from her collection Ghost Station published by Salt Image from Sandman Special 1 1991 DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. Used with permission. Stills from Orphe ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2011

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

ISBN 978-1-46830-181-6

Lives, Lies and the Iran-Contra Affair

A Fool and his Money: Life in a Partitioned Medieval Town

Pilate: The Biography of an Invented Man

Perkin: A Story of Deception

Being Shelley: The Poets Search for Himself

This book is dedicated to everyone who protested, But Orpheus isnt real.

That is the essential: to see everything within life itself, even the mystical, even death.

Rilke

On the morning of February 2nd 1922, Rainer Maria Rilke went up to his study and shut the door.

He was a slight man with large blue eyes that seemed, on cold days, to brim continuously with water. With a handkerchief,he dabbed the tears away. Neatness was in his nature. He wore a perfectly knotted tie; for his morning walks along empty countrylanes, a homburg carefully brushed, and a cane in hand; well-shined shoes. His drooping moustache was meticulously clipped,hiding a sensual mouth above a weak, timid chin.

For his first five years his parents had named him and dressed him as a girl. They had then dispatched him to a brutal militaryacademy. The damage was lasting. Against the odds he had become an Austrian poet of distinction, whose books by 1914 soldin thousands and went into several editions. But he retained a certain delicacy, an air of shyness, that hid his steel resolveand drew protective and passionate women into his life. One of them, Merline Klossowska, had helped him find this place towork in: a small, square fortress called the Chteau de Muzot, without electricity or running water, in the foothills of theFrench Alps.

The study looked out on the pretty woods and vineyards of the Valais, now winter-bare. It answered his longing for a roomof my own, with a few old things and a window opening onto great trees. Dark oak beams spanned the ceiling, low enough tomake him duck instinctively as he paced about, though he was not tall. Beside the window was a standing-desk, made exactlyto his specifications, at which he always wrote. In this room, as he had pledged in 1906, he would kneel down and stand updaily, alone, and keep holy all that befalls me.

All was in order. He was ready. The candlestick on the bookcase, the new glass-lidded box for tacks and pens razor-straighton the table, the porcelain vase standing exactly where it had stood before, though it held no roses now, for those were past,or yet to come. Somewhere on the bookshelves lay a French prose version of Ovids Metamorphoses, recently reread. Rilke had been steeping himself again in the story of Orpheus, the magician-singer of the ancient world,his love for Eurydice and his descent to Hades to rescue her. A Renaissance engraving of Orpheus by Cima da Conegliano, reproducedon a postcard, was also pinned over his desk. Merline had spotted it in a local shop. It showed a young man in pages clothes,under a spreading tree, singing sadly to a lira da braccio while two deer listened. It reminded Rilke, though he needed no reminding, of his mission as a poet.

It also helped preserve the memory of a young friend, Vera Knoop, who had died two months before. She was nineteen, and hadsuffered from a baffling glandular disease. For years she had astonished people with her dancing and her dark, strange, fiery loveliness until, at the end of childhood, she suddenly told her mother that she would not dance any more.In her last weeks Orpheus had begun to haunt her: invisibly playing music to which she raised her tired, wasting arms, gentlypushing the pencil with which she tried, wearily, to draw.

But Rilke would not think of her this morning. He was trying to finish a great symphony of poetry, his Duino Elegies, which sang of the sublime, violent interaction between angels and men. After ten years of neglecting it, inspiration wasbeginning to stir again. He dared not risk losing or unsettling it.

Consciously empty yet anticipating something, wrapping myself more and more closely round my heart, he took up his stationat the standing-desk.

And suddenly, Orpheus was there.

The singer of singers. To Rilke he needed no introduction; to us, perhaps, he does. We demand a curriculum vitae, a flyer or a calling card. Insteadhe brings music and the wind with him, and no information.

His origins are lost. In the beginning he was perhaps a vegetation god, a deity of growth, death and resurrection. Hence Orpheus,by one derivation: dark, obscure, out of the earth. But godhead gradually slipped away from him, leaving only a sense of electionand the power, through his music, to change landscapes, seasons, hearts.

To the Thracians, among whom perhaps he really lived thirty centuries ago, he was a king, a shaman and a traveller through the realms of the dead. To the ancient Greeks he was the first singer of holy songs and the founder of their mysteries,an enchanter who could make the stones skip, the trees dance and birds waver in the air. (He still can; ask him.) He was thecompanion of the Argonauts and their priest on the voyage to find the Golden Fleece: a teacher of beauty and order who waseventually torn apart, in Thrace, by followers of the wine god Dionysus and devotees of chaos.

By the fifth century BC he had acquired a wife, Eurydice, and when she died he went down to Hades, armed only with music,to bargain for her with the rulers of the Underworld. But the Greeks hardly cared for this part of his story. It was the Romans,especially Ovid and Virgil in their poetry, who made of him a lover so ardent that he challenged death. Both his love andhis art were pitted against annihilation, and though he failed, they became immortal. That is mostly why the world remembershim.

In this guise of sweet singer, lover and loser, Orpheus has wandered through history. Poets, artists and composers have constantlyevoked this figure, and still do. But the teacher and philosopher was not forgotten by Renaissance Florence or the nineteenth-centurytheosophists; the magician and spell-binder, familiar to the Greeks, was remembered by alchemists until Newtons time; hisadventure in Hell was allegorised as the journey of the soul by Boethius in the sixth century AD, as well as by Freud andJung in the twentieth. For at least sixteen centuries Christians easily imagined him, with his miracles and parables, hisredeeming power and his bloody, sacrificial death, as a forerunner of Jesus, though preaching with song in the forests ofancient Greece rather than the deserts of Judaea.