Table of Contents

ALSO BY ALEKSANDAR HEMON

Nowhere Man The Question of Bruno

For my sister, Kristina

And when he thus had spoken, he cried with a loud voice, Lazarus, come forth. And he that was dead came forth, bound hand and foot with rags, and his face was covered with a cloth. Jesus saith unto them, Loose him and let him go.

The time and place are the only things I am certain of: March 2, 1908, Chicago. Beyond that is the haze of history and pain, and now I plunge:

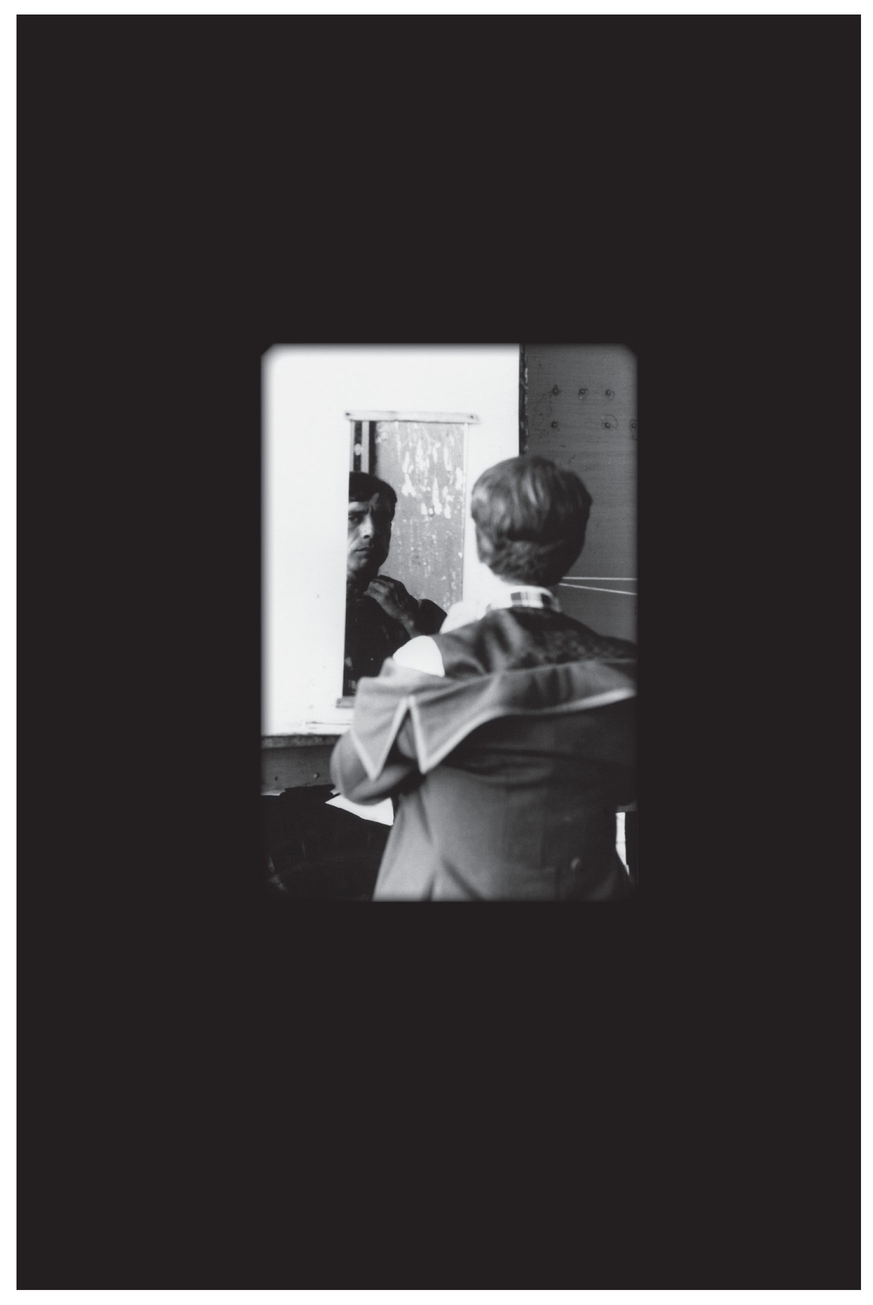

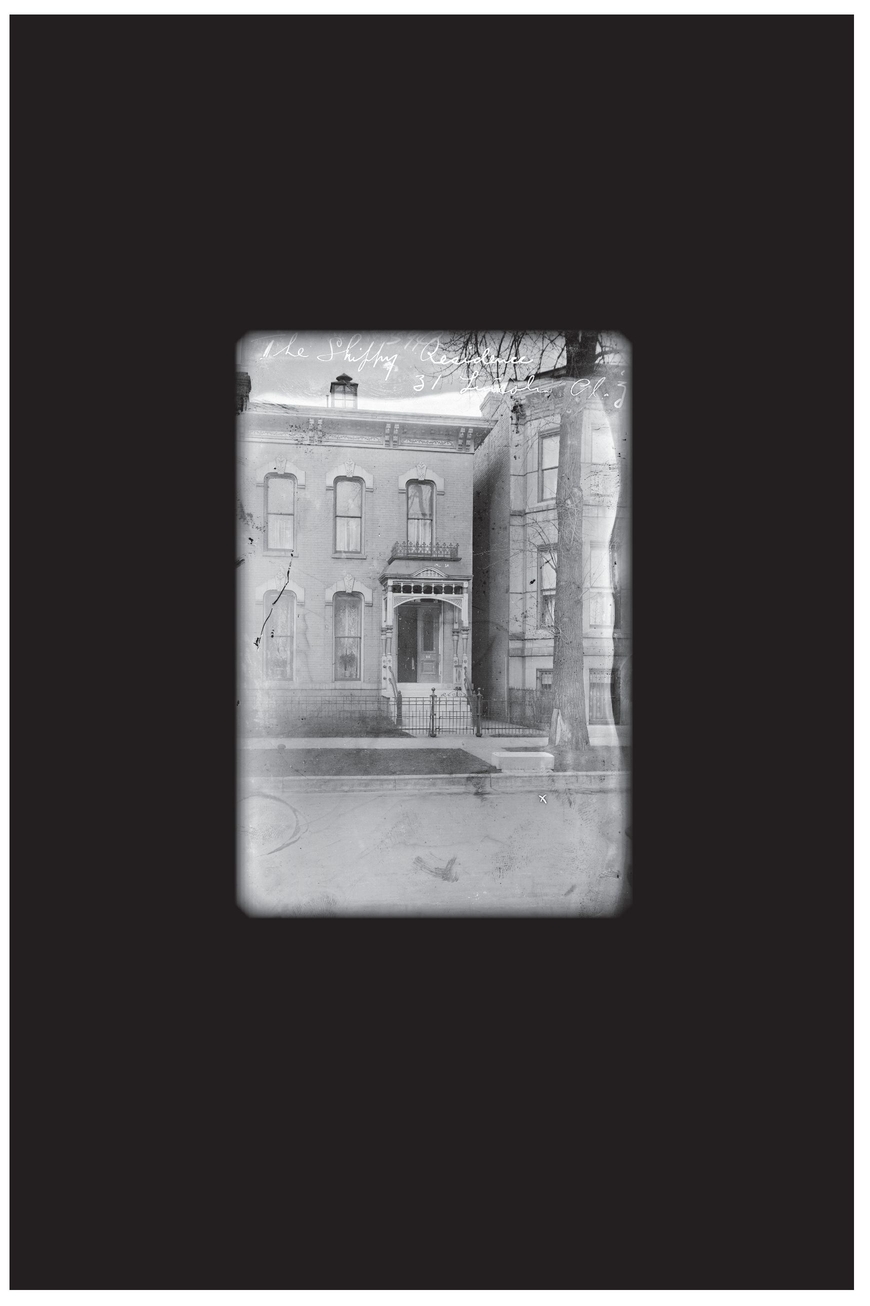

Early in the morning, a scrawny young man rings the bell at 31 Lincoln Place, the residence of George Shippy, the redoubtable chief of Chicago police. The maid, recorded as Theresa, opens the door (the door certainly creaks ominously), scans the young man from his soiled shoes up to his swarthy face, and smirks to signal that he had better have a good reason for being here. The young man requests to see Chief Shippy in person. In a stern German accent, Theresa advises him that it is much too early and that Chief Shippy never wishes to see anybody before nine. He thanks her, smiling, and promises to return at nine. She cannot place his accent; she is going to warn Shippy that the foreigner who came to see him looked very suspicious.

The young man descends the stairs, opens the gate (which also creaks ominously). He puts his hands in his pockets, but then pulls his pants upthey are still too big for him; he looks to the right, looks to the left, as though making a decision. Lincoln Place is a different world; these houses are like castles, the windows tall and wide; there are no peddlers on the streets; indeed, there is nobody on the street. The ice-sheathed trees twinkle in the morning drabness; a branch broken under the weight of ice touches the pavement, rattling its frozen tips. Someone peeks from behind a curtain of the house across the street, the face ashen against the dark space behind. It is a young woman: he smiles at her and she quickly draws the curtain. All the lives I could live, all the people I will never know, never will be, they are everywhere. That is all that the world is.

The late winter has been gleefully tormenting the city. The pure snows of January and the spartan colds of February are over, and now the temperatures are falseheartedly rising and maliciously dropping: the venom of arbitrary ice storms, the exhausted bodies desperately hoping for spring, all the clothes stinking of stove smoke. The young mans feet and hands are frigid, he flexes his fingers in his pockets, and every step or two he tiptoes, as if dancing, to keep the blood going. He has been in Chicago for seven months and cold much of the timethe late-summer heat is now but a memory of a different nightmare. One whimsically warm day in October, he went with Olga to the lichen-colored lake, presently frozen solid, and they stared at the rhythmic calm of the oncoming waves, considering all the good things that might happen one day. The young man marches toward Webster Street, stepping around the broken branch.

The trees here are watered by our blood, Isador would say, the streets paved with our bones; they eat our children for breakfast, then dump the leftovers in the garbage. Webster Street is awake: women wrapped in embroidered fur-collar coats enter automobiles in front of their homes, carefully bowing their heads to protect the vast hats. Men in immaculate galoshes pull themselves in after the women, their cuff links sparkling. Isador claims he likes going to the otherworldly places, where capitalists live, to enjoy the serenity of wealth, the tree-lined quietude. Yet he returns to the ghetto to be angry; there, you are always close to the noise and clatter, always steeped in stench; there, the milk is sour and the honey is bitter, he says.

An enormous automobile, panting like an aroused bull, nearly runs the young man over. The horse carriages look like ships, the horses are plump, groomed, and docile. Electric streetlights are still on, reflected in the shop windows. In one window, there is a headless tailors dummy proudly sporting a delicate white dress, the sleeves limply hanging. He stops in front of it, the tailors dummy motionless like a monument. A squirrelly-faced, curly-haired man stands next to him, chewing an extinguished cigar, their shoulders nearly rubbing. The smell of the mans body: damp, sweaty, clothy. The young man stomps each of his feet to make the blisters inflicted by Isadors shoes less painful. He remembers the times when his sisters tried on their new dresses at home, giggling with joy. The evening walks in Kishinev; he was proud and jealous because handsome young fellows smiled at his sisters on the promenade. There has been life before this. Home is where somebody notices when you are no longer there.

Responding to the siren smell of warm bread, he walks into a grocery store at Clark and WebsterLudwigs Supplies, it is called. His stomach growls so loudly that Mr. Ludwig looks up from the newspapers on the counter and frowns at him as he tips his hat. The world is always greater than your desires; plenty is never enough. Not since Kishinev has the young man been in a store as abundant as this: sausages hanging from the high racks like long crooked fingers; barrels of potatoes reeking of clay; jars of pickled eggs lined up like specimens in a laboratory; cookie boxes, the lives of whole families painted on themhappy children, smiling women, composed men; sardine cans, stacked like tablets; a roll of butcher paper, like a fat Torah; a small scale in confident equilibrium; a ladder leaning against a shelf, its top up in the dim store heaven. In Mr. Mandelbaums store, the candy was also high up on the shelf, so the children could not reach it. Why does the Jewish day begin at sunset?

A wistful whistle of a teapot in the back announces the entrance of a hammy woman with a crown of hair. She carries a gnarled loaf of bread, cradling it carefully, as though it were a child. Rozenbergs crazy daughter, raped by the pogromchiks, walked around with a pillow in her arms for days afterwards; she kept trying to breast-feed it, boys scurrying at her heels hoping to see a Yid tit. Good morning, the woman says, haltingly, exchanging glances with her husbandthey need to watch him, it is understood. The young man smiles and pretends to be looking for something on the shelf. Can I help you? asks Mr. Ludwig. The young man says nothing; he doesnt want them to know he is a foreigner.

Good morning, Mrs. Ludwig. Mr. Ludwig, a man says as he enters the store. How do you do today? The little bell goes on tinkling as the man speaks in a hoarse, tired voice. The man is old, yet unmustached; a monocle dangles down his belly. He lifts his hat at Mrs. and Mr. Ludwig, ignores the young man, who nods back at him. Mr. Ludwig says: How do you do, Mr. Noth? How is your influenza?

My influenza is rather well, thank you. I wish I could say the same thing for myself. Mr. Noths walking stick is crooked. His tie is silk but stained; the young man can smell his breathsomething is rotting inside him. I will never be like him, thinks the young man. He leaves the cozy small talk and walks over to the board near the front door to browse through the leaflets pinned to it.