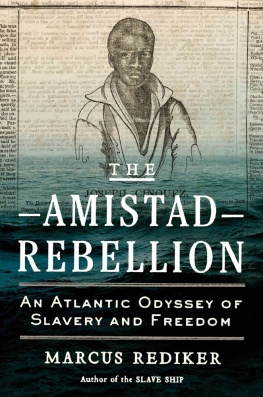

Something like a pirate, announced a New York Globe headline on an August morning of 1839: The pilot boat Blossom, on Wednesday last off the Woodlands, fell in with a Baltimore-built schooner of about 150 tons, painted black with a white streak, two gilded stars on her stern, having on board apparently twenty-five or thirty men, all blacks, who requested something to eat and drink. The Blossom supplied them with water and bread. The next day took them in tow when they attempted to board the pilot boat, which, to escape, cut the hawser. There were no persons on board that could speak English, and they appeared well supplied with cutlasses, but what their intentions were could not be understood.

So began a strange series of events that was to bedevil the diplomatic relations of England, Spain, and the United States for a generation, intensify bitterness over the question of slavery, and at one of its most dramatic points, lead an ex-president of the United States to go before the Supreme Court and castigate the administration then in office. Because of the mysterious schooner and its black crew, thousands of white Americans turned their thoughts to Africa, and with pangs of conscience, felt an urgent need to send it missionaries instead of slave traders. Africa has not been quite the same since that August morning of 1839 - nor, in a significant way, has America.

The Globe story aroused lively interest. The public was not accustomed to such excitement as a shipload of black men with cutlasses. Pirates were a thing of the past, at least in the North Atlantic. Slavers never ventured into coastal waters, for the slave trade had been outlawed since 1808. And the country had been at peace for twenty-five years. It had been a dull summer for news, with nothing much to put into headlines beyond occasional trouble with Indians on the faraway frontier. Martin Van Buren was in the third year of his presidency, with pre-election fervor still many months in the future.

During the second and third weeks of August, the newspapers made much of the mysterious schooner - long, low, and black - that continued to make Flying Dutchman-like appearances along the coast. Several ships reported having seen her in the distance, a strange apparition with tattered sails, a green bottom, no flag, and no apparent destination.

On August 20, the schooner Emmeline, out of New Bedford, sighted the stranger off Barnegat Bay and came alongside her. According to the Emmelines captain, the lettering on her stern appeared to read Hempsted. She carried fore-topsail, with the rest of her sails blown to pieces. The captain counted twenty-five nearly naked black men on the deck. Some of these indicated by signs that they were out of drinking water and in a state of starvation. The Emmeline took the schooner in tow, but when the black men armed themselves with sugar-cane knives and cutlasses, cast her off again. Shortly thereafter, seven of the armed blacks came alongside in a boat, asking for water. The captain told them to go back and get their papers. They did not return. An hour or so later, the crew of the Emmeline noticed a white man on the schooners deck, but darkness fell before he could be observed closely. The next day, the Emmeline sighted the ship again, about eight miles away, firing three guns.

The crew had a very savage appearance, the Emmelines captain later reported, and the white man supposed to be the captain had a piratical look with a large moustache.

In New York, the Collector of the Port dispatched a cutter to look for the strange ship and wrote to his counterpart in Boston, advising him to do the same. The steam frigate Fulton - the only steam vessel in the United States Navy - was also pressed into service, but since she could carry only enough fuel for four days, she was unable to venture far from New York harbor. A day or two later, another pilot boat arrived at New York with a report of a peculiarly acting ship that had a large eagle on her bow and a name that looked like Almeda.

On the morning of Monday, August 26, a bright, warm morning, two sea captains of Sag Harbor, Long Island - Henry Green and Peletiah Fordham - were shooting birds among the dunes of Long Islands eastern tip. To their astonishment, they came suddenly face to face with four black men, naked except for blankets. After a moment of consternation on both sides, a conversation of sorts was begun, by means of sign language and a few key words such as America and Africa. The blacks made it clear that they would like to know what country they were in and whether its people were slaveowners. On being assured that Long Island was not slave country, they led the two captains to the top of the dunes and pointed out a ship lying at anchor a mile or so to the north of the beach. She was a long, low, black schooner with an eagle on her bow, her sails in tatters, and no flag.

A boat was drawn up on the beach, guarded by several more black men. Some of them wore blankets, some merely bandannas tied around their loins, and one nothing but a white coat. But what Green and Fordham noticed in particular was that most of them sported necklaces and bracelets made of gold doubloons. The black who appeared to be the leader, a striking and very strong-looking young man, wore a necklace that, as Green afterward said, looked as if it were made of at least 300 coins. When asked where these trinkets came from, the leader indicated that there were many more doubloons aboard the ship - two trunkfuls, in fact - and that these would belong to anyone who would get them provisions and then help them sail the ship to their home in Africa.

Captains Green and Fordham said later that they suspected things were not right. They also soon realized that they were not the only Long Islanders to have encountered the strangers, for in a few minutes a party of blacks returned from a foraging expedition, bringing with them a loaf of bread, a bottle of gin, and two dogs, which they had bought from farmers and paid for royally with doubloons. Green suggested that the Africans go at once and get their trunks and bring them to the beach. After that, he told them, he would sail the ship to Africa.

Some of the blacks rowed back to the ship and presently returned with two heavy, rattling trunks and more of their companions, making the total number on the beach about twenty. At this juncture, a brig of the United States Coast Guard, the Washington, hove in sight off Gardiners Point. Green and Fordham, whose intention it was to take the ship into Sag Harbor and claim salvage rights to her, were considerably annoyed to see the Washington come about and lower a boat. The black men on shore piled hastily into their own boat and tried to get back to the schooner, but on the way, they were intercepted by the boat from the brig, which was armed, and taken prisoner. The brigs commander, Lieutenant Gedney, lost no time in boarding the rattletrap schooner. After ordering all hands below at pistol point, Gedney proceeded, with caution, to look for the piratical-looking white captain with a large moustache, of whom he had read in the newspapers. Suddenly an elderly white man, tattered, bearded, and sobbing, burst out upon the deck and threw his arms around Gedneys neck. He spoke only Spanish, but a minute later another Spaniard appeared from below, a young man who, it developed, had been educated in Connecticut and spoke fluent Yankee English. He lost no time in pouring out an extraordinary story.

The ship was the Amistad (Friendship), bound out of Havana for the Cuban coastal town of Puerto Prncipe. She had sailed on June 28 with five white men aboard - the captain and owner, Ramn Ferrer; the older man, Pedro Montes; the younger, Jos Ruiz; and two sailors. Besides these, there was a mulatto cook and a black cabin boy, Antonio, both the property of Captain Ferrer; four child slaves belonging to Montes - three little girls and a boy; and forty-nine male adult slaves, belonging to Ruiz. Montes and Ruiz had just bought their slaves in Havana and were returning with them to their homes in Prncipe, along with an agreeable cargo that included such things as silks, cottons, lace, looking glasses, books, bridles, saddles, pictures, fruit, olives, and wine, as well as a generous supply of gold doubloons.