Pitch Publishing

A2 Yeoman Gate

Yeoman Way

Durrington

BN13 3QZ

www.pitchpublishing.co.uk

James Moor 2013

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the Publisher.

First published and printed in 2013

First published in eBook format in 2013

eISBN: 978-1-909626-04-1

(Printed edition: 978-1-90917-870-0)

eBook Conversion by www.ebookpartnership.com

Contents

Foreword

I T happens less now that Ive written more books but, when Behind the Curtain came out, you could pretty much guarantee the question would come up at some point in any discussion of it: why eastern Europe? There were many reasons some of them mundanely pragmatic and financial but the romantic strand began in 1984 when I went to Bohinj in what is now Slovenia. I was seven and it was the first time Id ever been out of Britain.

I remember quite clearly stepping out of the plane for the first time at Ljubljana airport and being overwhelmed by the sense of heat and the scent of the pines: so this was abroad. I loved it. Yugoslavia, it seemed to me, was basically the Lake District but with better weather and more interesting food, particularly the ice cream. There was a little hut by the mini golf course in the park that served a couple of dozen flavours. Blackcurrant! Lemon! Cherry! Stuff with Italian names that I didnt trust! And this at a time when, at home, Walls Neapolitan seemed like a treat. We went back another four times before the war began: to Bovec and Portoro, to Kranjska Gora, to Bohinj again, to abljak in what is now Montenegro.

Coming back from abljak to the airport at Tivat, the fan belt on the bus broke, forcing us to take a taxi. With missing the flight a serious threat, the driver raced along back roads through the mountains. At one point we came upon an army roadblock. There was a long discussion between an officer and the driver before they finally agreed to let us through, with the instruction not to look anywhere but straight ahead. Even so, I remember dozens of soldiers, at least one of whom was carrying a bazooka on his shoulder. Theyre training, said the driver when we got to the other side. For the war. That was 1990.

We clearly didnt quite understand the significance of that because the next year we were booked up to go to Istria, only to be forced to cancel because of the conflict. We ended up going to Wick in north-eastern Scotland instead which, frankly, wasnt as good. I never went on another summer holiday with my parents.

Looking back, I can see that Yugoslavia wasnt an obvious holiday choice but at the time, knowing no different, it felt entirely natural. My dad had been to Croatia in 1962, when Tito first opened the borders, on what was essentially a lads holiday he had tales of going out with the fishing fleet and having to hide from port officials determined to keep tourists to the designated beaches when they came back to shore and my mam, coincidentally, had been to the same resort a year later. Both of them had been back repeatedly, first independently and then together. My nana and grandad, my mams parents, had also been frequently and had an etching of the bridge in Mostar on their living room wall. To me as a kid, Yugoslavia was just a place people went for their holidays; it didnt seem odd, even if, when I think about it, I dont think anybody else at school went there. My dads father had been an engineer in the merchant navy, so perhaps he was slightly more conditioned to be adventurous in his travel choices, but essentially I think my parents liked it because it was beautiful, sunny and cheap.

But of course what that last holiday had revealed was that, beneath the surface and not far beneath were serious political tensions. And it was that that came to fascinate me as I became a journalist and started going back to the former Yugoslavia to cover football, particularly given the clear intersection between football and politics and the war. But theres also something about the football itself that attracted me, the combination of brilliance and mental fragility, the sense that Yugoslavia and then the former Yugoslav states somehow both overachieve given their population and yet also should have done far better historically, perpetually self-destructing at the vital moment: Yugoslav football is a litany of lost finals and semi-finals (its tempting, but probably over-simplistic, to suggest a significance in the fact that the key moment in Serbian history, romanticised beyond all reality now, was the defeat to the Ottomans on the Field of Blackbirds in Kosovo in 1389), with one notable exception: Red Stars victory in the 1991 European Cup Final as Yugoslavia spiralled into conflict a glorious pan-Yugoslav triumph (there was at least one player from five of the six republics in that side) achieved a little under a month before Slovenia formally seceded from the federation to announce the death of Yugoslavia.

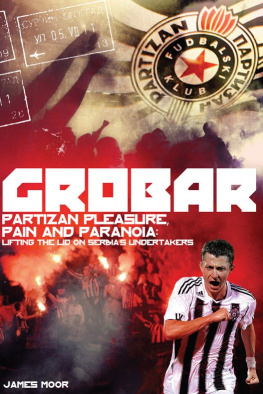

Presumably its because of that success that Red Star seem to be the best-known Serbian side today. Or perhaps its because it was they who were playing Dinamo Zagreb when Zvonimir Boban kicked a policeman in 1990, or because it was their ultra group, the Delije, that Arkan led and from which he drew many of his paramilitaries during the war. Perhaps its even as simple as the fact that after the war, they had better PR, advertising their role in the toppling of Slobodan Miloevi. Whatever the reason, one of the joys of this book is seeing Belgrade football from the Partizan side of the divide.

More generally, theres something very encouraging about the fact that a book about Partizan can be published. Its only two decades since three books Pete Daviess All Played Out, Nick Hornbys Fever Pitch and Simon Kupers Football Against the Enemy changed the face of football publishing. Those three books persuaded publishers both that good, intelligent books could be written about football and that they would sell. The result has been an extraordinary boom in football literature, much of it following Kuper in turning to international themes, using football as a means of examining another culture or society, something that, as just about the one universal cultural mode, it is ideally equipped to do. This is a fine addition to that genre, but it is more than that. Publishing is an industry beset by gloom, as bookshops close and the major conglomerates lay off staff, but if its possible to bring out a book about the second most famous team in Belgrade, it is at least getting something right.

Jonathan Wilson, 2013

Authors Acknowledgements

S EVERAL people played a huge role in helping this book come into existence, in their different ways. In chronological order: firstly to my Mum and Dad to my Mum for being the person who got me interested in reading and writing and told me from an early age that I could do this if I wanted to (although she might not have envisaged quite so many references to the word pika when she said that), and to my Dad for taking me to my first ever football game Crystal Palace v Arsenal at Selhurst Park in 1989, a bustling 1-1 draw that set the tone for decades of dependence on the live footballing drug.

Next page