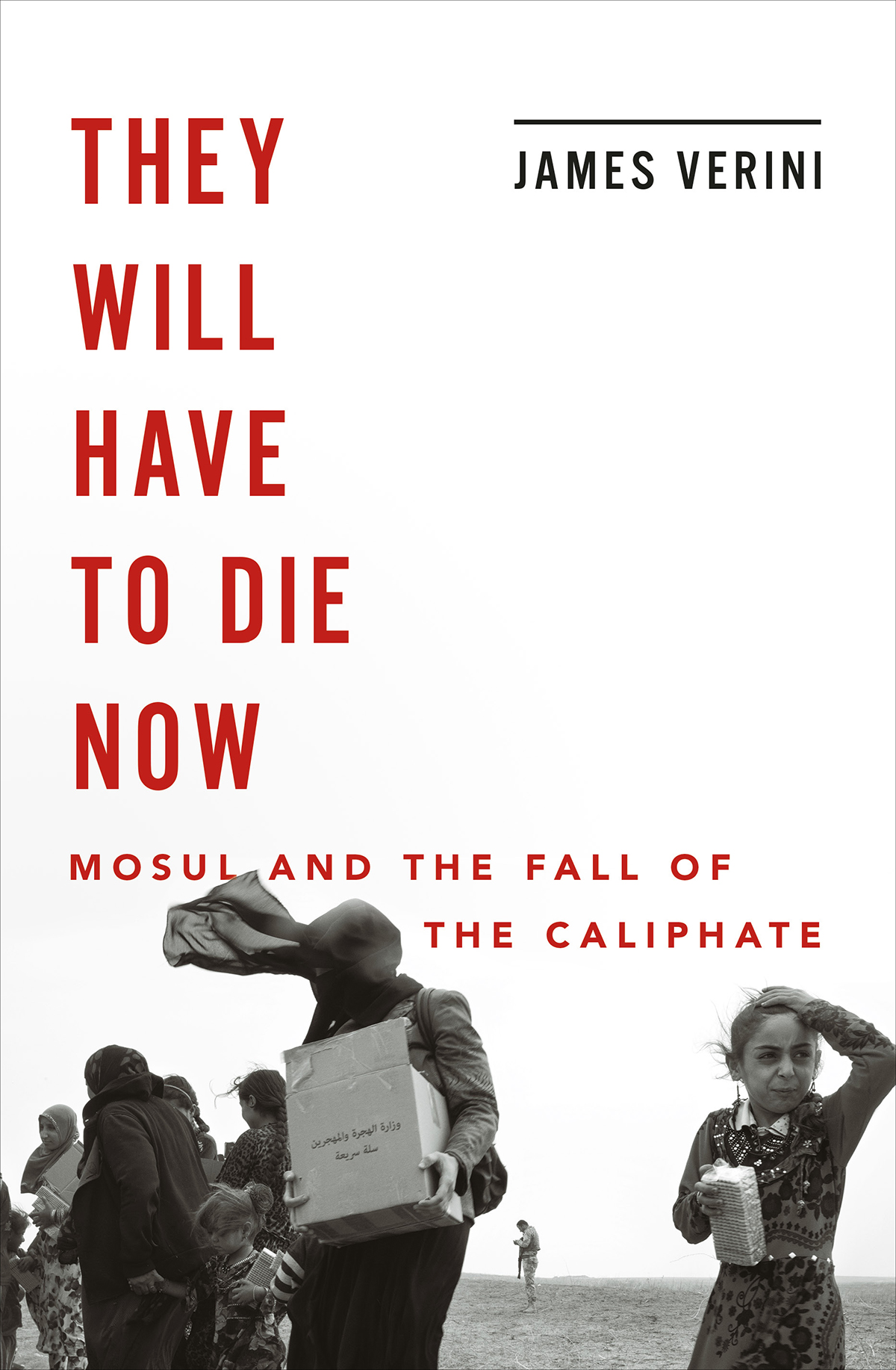

THEY

WILL

HAVE

TO DIE

NOW

MOSUL AND THE FALL OF THE CALIPHATE

JAMES VERINI

To Aya, Amina, Maha, Zainab, Zina, Clementine, and Vivian.

Im sorry for the world were giving you.

Please help us make it better.

And to Christopher Hitchens.

You were wrong about Iraq, but right about

most everything else.

Of course he has a knife. He always has a knife. We all have knives. It is eleven eighty-three and were barbarians. How clear we make it. Oh, my piglets, were the origins of war. Not historys forces nor the times nor justice nor the lack of it nor causes nor religions nor ideas nor kinds of government nor any other thing. We are the killers: we breed war. We carry it, like syphilis, inside.

ELEANOR OF AQUITAINE IN The Lion in Winter

CONTENTS

I

ZAHRA

I have come forth alive from the land of purple and

poison and glamour,

Where the charm is strong as the torture, being

chosen to change the mind

G.K. CHESTERTON

T wo weeks into ground operations to recapture Mosul, Iraqi troops breached the city limits, fighting their way in through a series of suburbs and neighborhoods in the southeast. But for another few weeks after that they could go no farther on the main access road into east Mosul than a hill on the citys outer rim. On the crest of the hill, astride the road, Islamic State fighters had lathered an embankment of rubble and scrap. By the time you noticed the embankment and its impassibility, bullets were already flying overhead. Then you noticed, between you and the embankment, a panorama of what would happen if you insisted on continuing forward. To the right of the access road was the apartment building from which the bullets flew and, to its left, a cemetery.

It was the fall of 2016, and the jihadis had been fighting on the back foot long enough that they knew a good defensive position when they saw one. They were understandably reluctant to give up the apartment building, really more of a complex of buildings, as you learned when you got a better look at it, and as perfect in its quiet ugly menace as it was in its situation. It overlooked not just the access road but some of the districts into which the troops were trying to push. From the buildings many exterior planes of sickly pebbledash and rust-stained stucco protruded balconies and roofs, a dealers choice of positions in which the Islamic State fighters set up machine-gun emplacements and snipers nests. The Iraqi troops would hose down the outside of an apartment with 50-caliber fire, or send a grenade into a window, and then another jihadi would appear in another window returning fire. The Islamic State had been in fighting retreat for over a year, had ceded most of its ground in Iraq, and yet here the jihadis still were, popping up, shooting back when not shooting first. If you couldnt admire their pluck, you had to marvel at it.

Why those buildings werent reduced to rubble with ordnance I never learned. The international coalition backing the Iraqi ground forces was flying sorties day and night over Mosul and a constellation of artillery firebases surrounded the city. Some mornings the strikes were constant, making the whole city quake, the atmosphere pulse and bellow. Most likely the jihadis were keeping the apartments stocked with civilians. They did this. When they couldnt get enough Moslawis to serve as human insulation and cannon fodder they imported them from surrounding villages, and the invisible presence of who knew how many innocents inside the apartment complex added to its menace. The place was ominous in the literal sense. It issued omens of an extensive, filthy, many-angled fight. It was the sort of frowning pile you had to see only once to think Well of course armed zealots would be shooting at me from there.

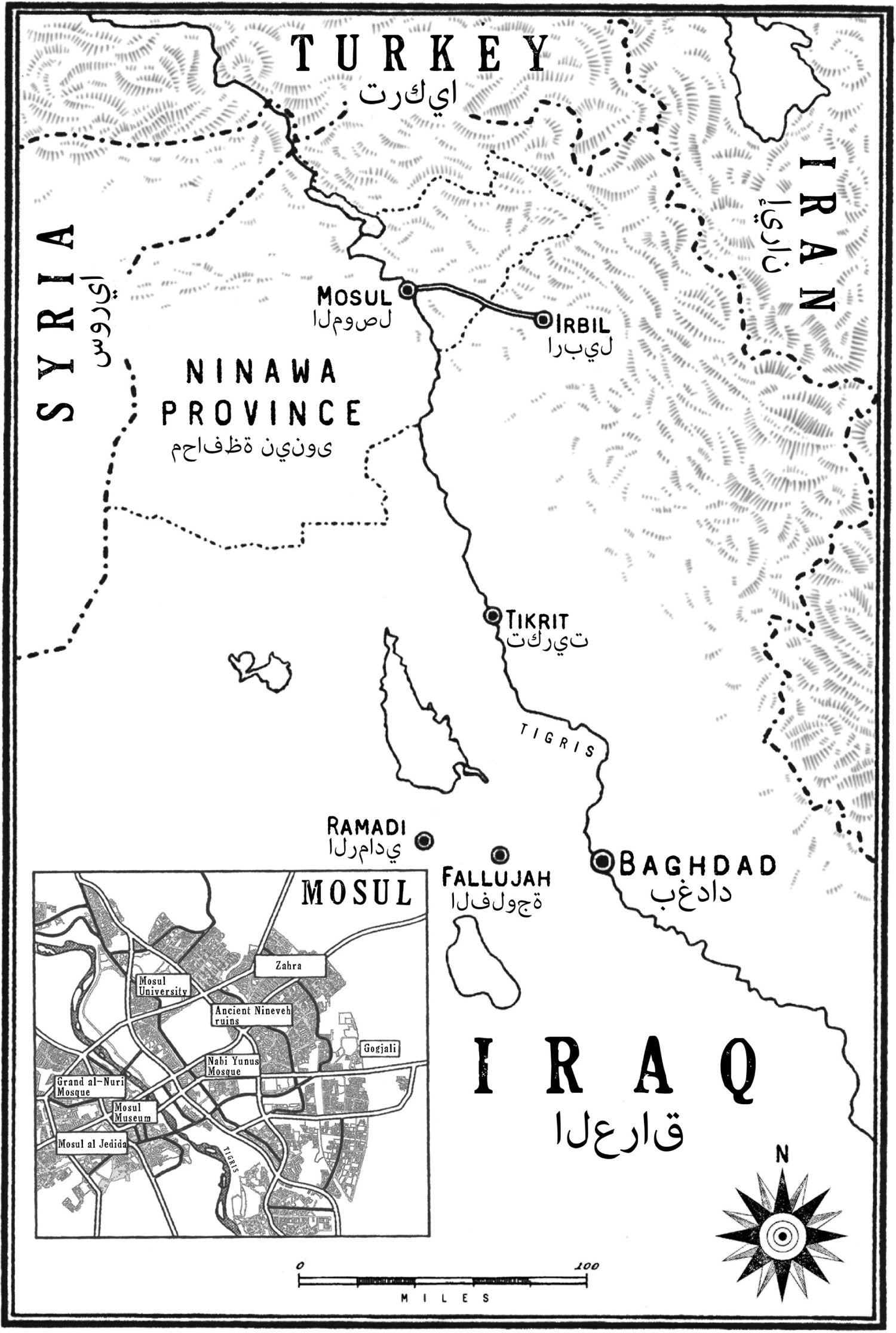

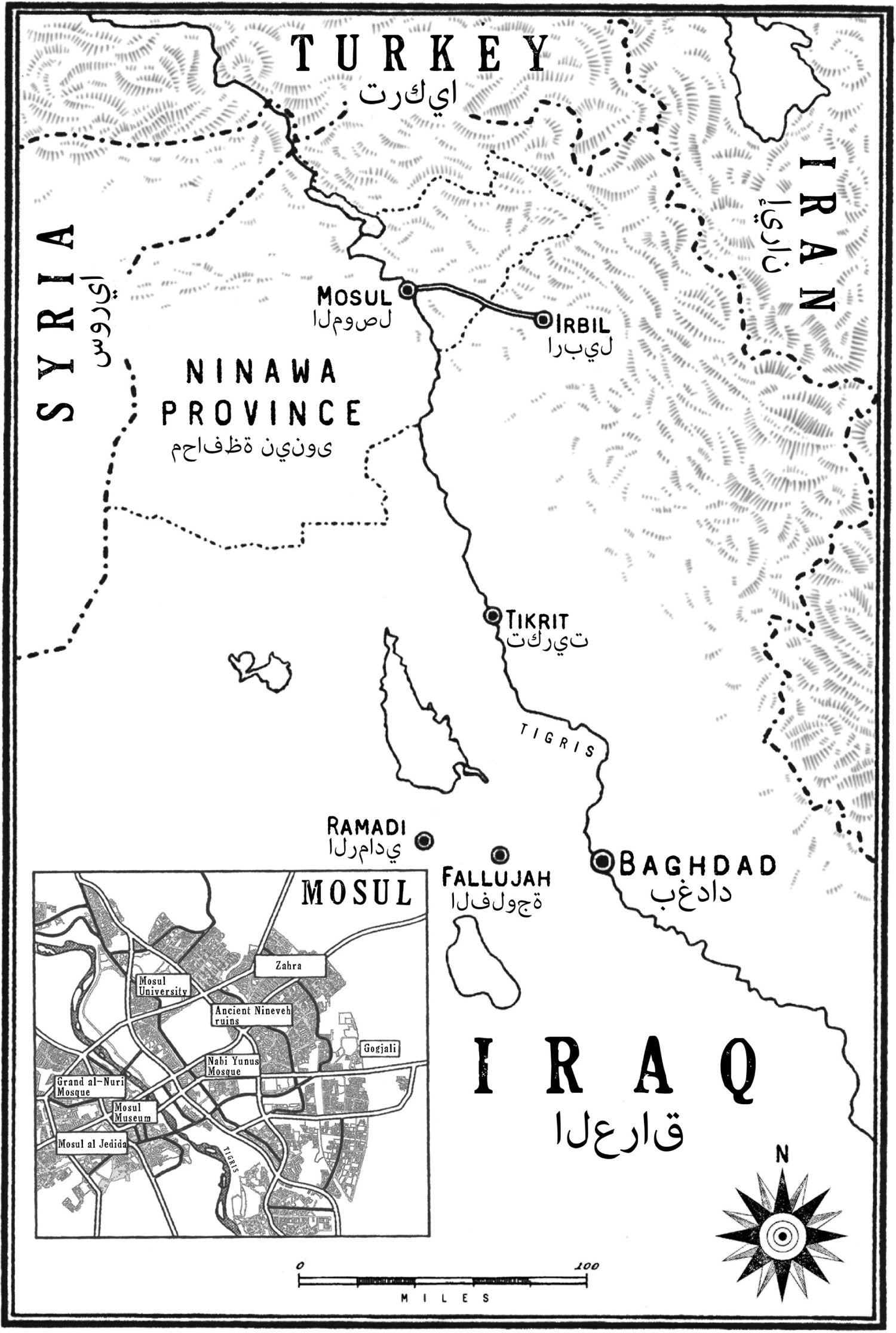

The Iraqi troops had, with great effort and bloodshed, established a small headland of control in a district to the north of the access road, beyond the reach of the gunmen in the apartments. To get to this district their convoys took a right off the road about a hundred meters downhill from the embankment, onto a partially paved side street that quickly degenerated into a dirt track. The neighborhood into which they drove, Gogjali, was as poor as Mosul got. About four hundred miles north of Baghdad, Mosul is the capital of the governate of Nineveh, the agricultural heartland of Iraq. On the Tigris, which bisects Mosul into its eastern and western halves, and near the borders of Turkey and Syria, the city has been a hub of trade, licit and illicit, for centuries. The results can be seen in Mosuls many mansions and its beautiful marble-and-tile mosques. Gogjalis mosque was a cinderblock box, its narrow streets unpaved, the privacy walls of its one-story houses still mudbrick. It had been one of the first neighborhoods seduced by the jihadis, you heard. When the Islamic States clandestine recruiters had started approaching Moslawis, whispering about an impending takeover, they had made short work of winning over people here. Look at those big houses down the hill nearer the river. You can live in one of those if you join us.

Gogjali was now the beginning of the rear on the eastern front, the only battle front in Mosul where the fighting was steady. The Iraqi 9th Division, armored and stodgy and questionable, was probing tentatively about the citys southeastern edge, and the better but not entirely dependable 16th was somewhere closer by, while the federal police and paramilitary forces were stirring around. But it was here in the east that the special forces formation leading the invasion of Mosul, the Counter-Terrorism Service, had put the first real puncture in the Islamic States defenses. It was through this puncture that the main part of the Iraqi infantry, ten thousand strong, was trickling and would soon pour. The Islamic State had started life as an insurgency, using insurgent tactics, but now it was a regime, a government, even, in its way; it held territory, it had in Mosul Iraqs second or third most populous city (depending on who did the counting), and now it would have to fight a conventional battle over territory, one government versus another.

Gogjali was also home to what, in those early days of the battle, was the Iraqi troops only frontline triage station. What few CTS medics there were had taken over an abandoned home and an adjoining vacant lot. Every morning they set up shop in the lot, carrying out their gurneys and rolls of gauze and squeeze bottles of iodine and IV kits, most of it donated by foreign charities.

Early one morning, the front line was just beyond the triage station. The pounding of airstrikes and artillery and the chatter of gunfire reverberated through the pall of dust and smoke and moist hazethe rainy season was beginning. The procession of casualties into the lot was already incessant. I arrived as a civilian caught in a shelling was carried in. He was put on a gurney. In moments, he was dead. His brother collapsed onto the body, weeping and hollering. He flung himself to the ground, still weeping and hollering and now smacking himself.

A CTS squad had been ambushed. A pair of bloodied soldiers lay on stretchers, too dazed to take note of the mourner writhing in the dirt beside them. A major was carried in by his limbs by four of his men as blood pumped from a gunshot wound in the rear of his thigh. Though clearly in excruciating pain, when a medic went to roll up the majors sleeve in order to put in an IV, the major got it in his mind the man was trying to lift his watch and he sat up, wheezing and flailing his arms in protest. In the late morning, the fighting quieted as the jihadis went to mosque. This happened every day, but on Fridays the lull was longer and particularly inauspicious. On Fridays the Islamic State imams gave sermons.

Next page