Table of Contents

Guide

2015, 2019 Juan Jos Martnez dAubuisson

English translation 2019 OR Books

All rights information:

Visit our website at www.orbooks.com

First printing 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except brief passages for review purposes.

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress.

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Typeset by Lapiz Digital.

Published by OR Books for the book trade in partnership with Counterpoint Press.

paperback ISBN 978-1-949017-15-1 ebook ISBN 978-1-949017-16-8

Contents

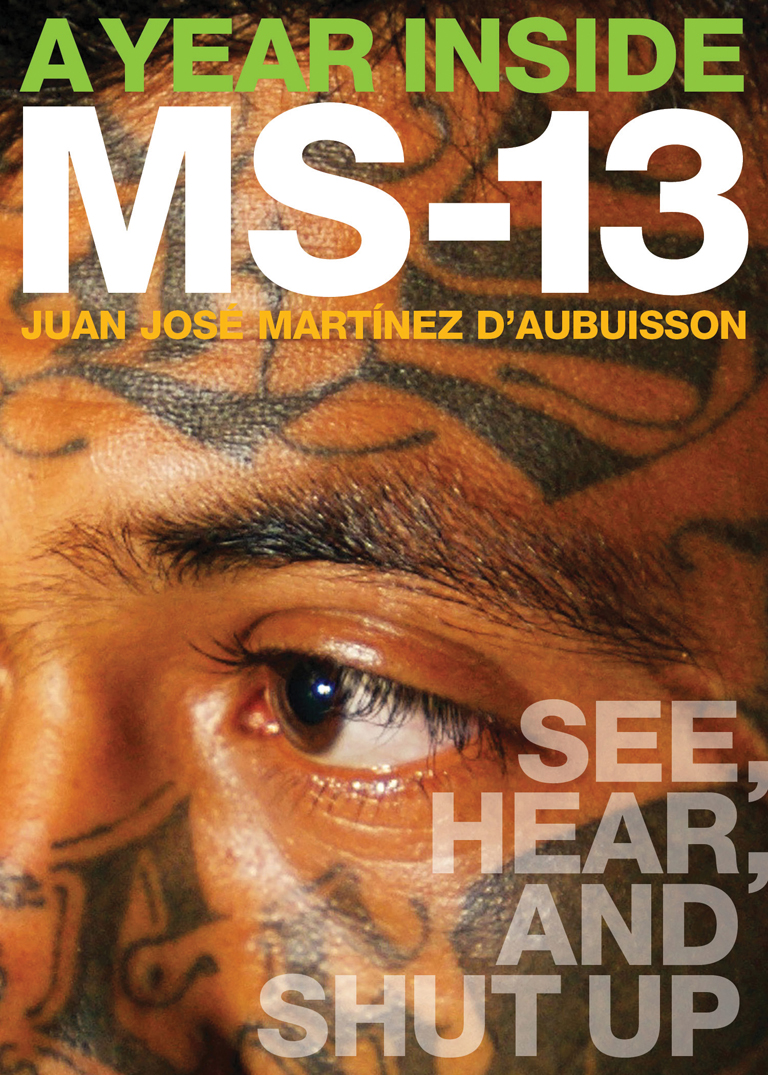

J UAN HAD AN old motorcycle. It was an inexpensive model, without gears even, some cheap Chinese brand that no enthusiast would recognize. Juan called her Samantha. Several times a week, Juan and Samantha had to traverse several neighborhoods dominated by the rival gang, Barrio 18, in order to get to Juans research site in the last neighborhood on the hill: the Buenos Aires neighborhood in San Salvador, MS territory. El Salvador is a country with more dividing lines than youd find on a map. The unmapped lines, the ones delineating rival gangs, are, if anything, more real than those found on maps.

One night in 2010, Juan was returning from the Buenos Aires neighborhood, Samanthas feeble motor straining. He had spent the day conducting an ethnographic study of Guanacos Criminales Salvatrucha, an MS-13 clica. Samantha, now in Barrio 18 territory, sputtered to a halt. It was night, he was a young man on a motorcycle; he was a young man, tattooed and long haired on a motorcycle; he was a young man, tattooed and long haired and on a motorcycle that had just stopped in enemy territory. Juan told me one night over a drink that he knew this could end very badly. He weighed his options: call the cops, continue on foot, seek help at a strangers door... and picked the best one: beg Samantha to move. He asked his cheap Chinese motorcycle to please move. He promised her a full tune-up if she got him out of Barrio 18s hood. And just as the shadows crept up, with a kick of the lever Samantha sputtered alive, and begrudgingly took them to safety. Sometimes it is necessary to be a little mad in order to conduct the sort of work Juan discusses in this book. It is necessary to set aside logic and rationality and beg a motorcycle to come back to life.

Juan is an anthropologist. Juan is an anthropologist dedicated to studying gangs, primarily Mara Salvatrucha, but hes also had encounters with Barrio 18 and the legion of deportees from the US who, while there, joined one of the dozens of Latino gangs from Southern California who refer to themselves as Sureos (Southerners). Juan has interviewed founders of MS, leaders of MS, retirees, and pawns; also traitors to MS, victims of MS, and the officials who want them dead.

Juan is also my brother. That said, and I say this without hesitation: Juan is the academic who best understands the most dangerous gang in the world, the MS. He best understands them because as an academica word which each day commands less respecthes renounced the comfort of lecture halls and air conditioners; hes renounced the writing of abstract tracts accessible only to those with advanced degrees. As an academic, Juan has renounced the classist norms of academia that dictate whose stories are worthy of being told.

The greatest testament to Juans unorthodox style is this book. This book does not set out to be academic. However, it elucidates how a strange academic who talks to motorcycles made sense ofmakes sense ofthe most violent corner of the planet. When Juan played cops and robbers with neighborhood kids, he knew he was working. When Juan spent long evenings watching Destino, one of the clicas leaders, make bread, he knew he was researching. When Juan scrawled notes on how the gang coerced a town drunkard to buy them cigarettes, Juan knew this was his job. He knew it, too, when he was the only non-gang member present at their gatherings, and when Destino told him his inner secrets and when Little Down started to take control and Juan saw it all, due to his patience, due to his understanding that remaining is key. Each day hed arrive home with Samantha and a journal full of notes.

Sometimes, at family dinners or nights at the bar, you could tell that remaining was taking its own toll on him. Juan would speak like a gang member in flashes, as if it took him a few moments to distance himself from that which hed jotted in his journal.

What you are about to read are the field notes of a mad anthropologist who made the journey again and again to understand what it meant, as a community, to live with Mara Salvatrucha. Juan decided that the gang, for his readers, should cease to be two glaring initials and instead take on a new meaning, informed by names, dynamics, words, children, the dead, their homes...

Reading an academic who is allergic to air-conditioned lecture halls is a gift. Reading him on Mara Salvatrucha is doubly so. There exist few criminal groups about whom so many stupid things have been published. From the pretentiousa piece that sought to link the Maras and the Zetasto the ignorantthe editorial that tried to illustrate, with pictures of rock stars downloaded from the internet, the symbology of gang tattoos. There are (arent there always) pizzeria journalists who prepare and deliver articles in thirty minutes or less, that tell us of gangs, their satanic rituals and their perfect wickedness. There are condescending academics and NGOers who, without understanding a fraction of what Juan does, have built a career off pity, rendering gang members as perfect victims. The complexity of gangsand the people who join themis all too often cast aside. Much nonsense has been written on Mara Salvatrucha. It will keep being written, as long as pizzeria journalists lack the understanding or motivation to dig deeper.

Juan has a way with words. Dont take my word for it; you hold the proof in your hands. Juans writing has appeared in leading publications and he has researched MS for decades. He continues doing so now. At present, he is working on a biography of an ex-member of MS, an ex-hitman for MS, a traitor to MS. He has worked on this story for two years, during which time hes traveled to the hideout of the man with a bounty on his head.

MS matters in Central Americano one argues otherwisebut it also matters in Mexico, and plays a huge role in the lives of many Latinx communities in the United States. MS is an international brand that even now is attempting to open branches in Spain. The emergence of MS is testimony to the failure of states to deal with aimless and disenfranchised young men. It is this failure which led to the emergence of a gang of killers. See, Hear, and Shut Up is an insiders view into MS. When you read this book, you will not be watching events unfold from the balcony; rather, you will be transported there, front and center, as scary as that may be. Still, that is not the strongest argument for reading it. The strongest argument is Juans madness and tenacity. It is the tenacity of a man who mounts a motorcycle to a fearsome neighborhood time and time again, without being paid a cent, because he thinks what he is about to explain can change things. The strongest argument is that this madnessor this benevolence, whatever you may choose to call itmuch like good books on MS, is rare in this world.

Next page