The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

On a scorching, smoggy Friday afternoon in August, a Homicide Special lieutenant in downtown Los Angeles answers a call from a detective supervisor in North Hollywood.

I might have one for you, he says. We had a call-out last night in Studio City. A Russian lady shot in the chest. Lots of condoms around. Probably a call girl. Very attractive. But heres the kicker: the FBI has a tap on her phone.

Why? the lieutenant asks.

Dont know. Thats why were calling you. You want it?

Ill send some guys over this afternoon.

The lieutenant crosses the squad room and briefs Detectives Chuck Knolls and Rich Haro. This is their last day as partners. They had hoped to make it through the night without a corpse, but Knolls is first on the weekend on-call list, which officially began at noon today. He has to take the case. His new partner, currently on vacation, wont show until tomorrow. So Knolls and Haro will track a homicide together one last time.

Haro, who is fifty-five, has tired eyes, a thick black mustache, and a sun-lined face. The oldest detective in the unit, he is on the verge of retirement. A case he picked up two years agothe murder of a 468-pound Hells Angel known as Large Larry and his girlfriendis scheduled for trial Monday. He will be tied up in court for months. After the trial, Haro wants to stay at Homicide Special just long enough to solve a Guatemalan triple murder he has been investigating for the past year and a half. Then he will pull the plug.

Haro knows this might be his last homicide, and he is already feeling nostalgic about leaving the unit. During his sixteen years at Homicide Special and, before that, as a divisional detective, he has investigated hundreds of murders and has solved many of them. It has been a good run, but he is getting too old to stand on his feet all night at murder scenes, to jump out of bed at three A.M. after callouts, to work twenty-four hours straight, grab a nap, and then work another shift. He thinks back to his first interview at the unit, when a grizzled homicide detective known as Jigsaw John leaned over, Canadian whiskey on his breath, and asked, You speak any language besides Spanish?

Yeah, replied Haro curdy, aware that there was only one other Latino in Homicide Special. English.

Everyone in the room laughed, and he was accepted into the unit.

Haro has never been the diplomatic sort. When he arrived at Homicide Special, he addressed any colleague who annoyed him as Butt Licker. Butt Licker, or B.L., became his nickname, and he derived a perverse pleasure in the sobriquet; in the pre-politically correct days of police work, he handed out business cards with the initials B.L. beneath his name.

Haro feels like a dinosaur and worries that his style of investigation is outmoded. When he first joined the unit, detectives slowly, methodically sifted through leads and clues and hints of evidence. Because his caseload was lighter then, he worked at his own deliberate pace. The wave of intense detectives who have recently joined the unit are so harried and impatient that Haro believes the quality of their investigations suffers.

Knolls, who just spent a grueling five years investigating murders in South-Central Los Angeles and has been at Homicide Special only nine months, is one of these new, driven detectives. He is forty-four, with pale green, hard-to-read poker eyes, thinning sandy brown hair, and a solid build from daily weight-lifting sessions. Blunt, stubborn, and accustomed to taking charge, Knolls has clashed in the past with Haro, his only partner at Homicide Special. Neither detective regrets splitting up.

As the lieutenant finishes up his briefing, Haro wonders whether the case will keep him out all night. He has lost track of the number of mornings he has arrived at home as his family was waking up. This is one element of the job he is not going to miss.

Haro and Knolls grab their suit jackets and roll out in separate cars. The detectives cruise through downtown, heat waves shimmering in the distance, the horizon veiled by a tawny band of smog. Less than an hour after the call-out, they speed on the freeway toward North Hollywood.

On another day, in another century, in a city that even then was famous for its dark and disturbing crimes, private detective Philip Marlowe climbed the redwood steps to his small house in the Hollywood Hills, fixed himself a stiff drink, and listened to the cars rumble through a canyon pass. I looked at the glare of the big angry city hanging over the shoulder of the hills. Far off the banshee wail of police or fire sirens rose and fell, never for very long completely silent. Twenty-four hours a day somebody is running, somebody else is trying to catch him.

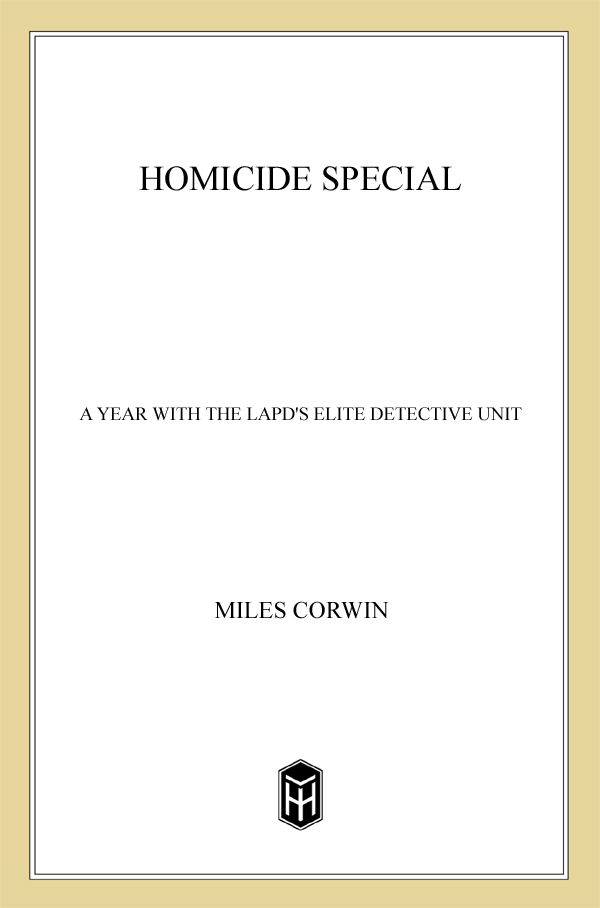

Today, half a century after Raymond Chandler wrote The Long Goodbye, twenty-four hours a day somebody is still running in Los Angeles. But while there are many more killers in this sprawling city now, and many more detectives trying to catch them, one thing has remained unchanged: a select downtown unit with citywide jurisdiction is still assigned to investigate the most brutal, most complex, most high-profile murders in Los Angeles. This unit is called Homicide Special.

Murders that involve celebrities are transferred from the local police divisions to Homicide Special. Organized-crime killings, serial murders, cases that require great expertise or sophisticated technology are investigated by Homicide Special. Any murder that is considered a priority by the chief of police is sent to Homicide Special.

A unit that tracks such singular murders is perfectly suited to Los Angeles. Teetering on the edge of the continent, the city has always been an urban outpost, conceived in violence, nurtured by deception, enriched by graft, riven by racial enmity, and plagued throughout its history by heinous homicides.

In the mid-nineteenth century, Los Angeles was known as the most murderous town in the entire West, a way station for the most vicious desperadoes, gamblers, grifters, and drifters. The only police chief in the citys history to die in the line of duty was murdered in 1870. East Coast reporters suggested that Los Angeles should change its name to Los Diablos. By 1900, L.A. was a cow town of about 100,000 people, unable to grow because of its limited water supply. The event that precipitated the citys population explosion and transformed it into a major metropolis was itself a crime: civic leaders hornswoggled farmers in the Owens Valley, 233 miles away, and siphoned off their water, enriching a handful of prominent men who had devised a real estate scam.

Once the water was flowing, millions poured into the city, lured by the promise of sunny days, balmy nights, ocean breezes, and the fragrance of orange blossoms. But beneath the palm trees and the pastel bungalows with their velvety lawns simmered the rage and resentment of rootless people whose troubles did not dissolve in the hazy sunshine. The burgeoning crime rate served as a sinister counterpoint to the Utopia promised by civic boosters and real estate hucksters. The seemingly benign, subtropical landscape also proved violent, beset by earthquakes, wildfires, flash floods, and deadly mud slides.