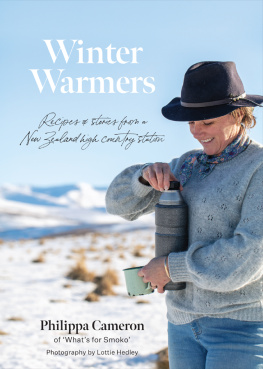

Dedicated to Ron

some of whose forbearance

is recorded in these pages

and

to our friends and neighbours

of the High Country

NOTE

In the pages that follow the full spelling of Mount Algidus refers to the station; where the mountain itself is mentioned the abbreviation has been used: Mt Algidus.

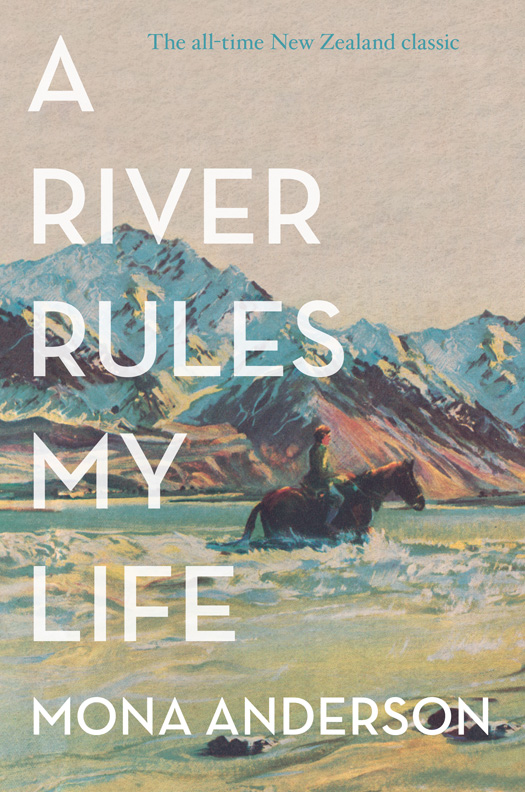

T he river was my Rubicon. I had heard stories about the terrible Wilberforce: so many people had been drowned in it. I tried not to think about the time when I would have to cross it. But the road had come to an end at a corrugated iron shed. Somewhere beyond it I knew we would find the station, Mount Algidus, a green, high-country oasis amid the snow and the tussock. There I could see myself leading a life of leisure. Perhaps I would ride round the sheep once in a while, with Ron, my tall, fair husband, solicitous by my side Darling, are you sure youre not tired? Meanwhile there was the river. This was the end of the road from the city. Here you either went on or you turned back.

I stood where I was, gazing at the waggon which was already waiting. It was a huge, clumsy old conveyance drawn by five great draught-horses, standing now with their faces hidden in nosebags. It looked enormously substantial and enormously forbidding. Ron and the teamster, whom he had introduced as Jim, stacked the last of my treasures and wedding presents aboard the monster. Vera, who had come this far with us, stood in cousinly silence by my side.

That thing, I said, must have come straight from the ark.

Its got two sets of wheels, said Vera thoughtfully.

Two sets of jolts too, Ill bet. Heaven help my wedding presents when it goes over a bump.

I wonder, mused Vera, how he manages to stay put in that drivers seat. Its perched half a mile up in the air.

Im wondering how Im going to stay put, perched on top of all that gear!

Jim removed the nosebags from the faces of his team, and lifting each shaft a little he kicked the prop from under and fastened it to the shaft. He had looked surprised to see Ron and me back from our honeymoon so soon but now he turned to me and said in a kindly way, Are you ready now? Weve a long road ahead of us.

Vera kissed me goodbye, then looked at the desolate riverbed, strewn with boulders the river bore with it down from the mountains, and at the rocky isolation stretching away on the far side.

Mona, she said, in a frightened voice, will I ever see you again? It was more a prayer than a question.

Dont be silly, I babbled at her in nervous excitement. If this old crate gets me there safely, surely to goodness it can bring me back again.

I clambered on to the waggon and found myself a perch on top of the furniture, where I sat clutching a precious vase Mother had given me and a large piece of wedding cake I had brought for the men on the station. I felt as if a lurch or the least puff of wind could bring me tumbling down. Ron heaved himself up and sat near the front. Jim climbed to his high seat, took hold of miles of leather ribbons, released the brake and called to the horses.

Now then Louie Jess Happy, come on! And none of your shenanigans!

The draughts lumbered forward, the waggon lurched alarmingly, nearly upsetting my balance, and we set off. At first we rumbled along a track on what I still thought of as my side of the river. As we approached a small bridge the leaders pretended to shy, pushing against one another with a rattling of chains and a creaking of harness.

Now, now! Jim called to them. Be jeepers, youve been over this bridge hundreds of times and no fox has jumped out at you yet! Then as we crossed the culvert he wheeled the team a little to the right and added, Whist now, lets get over this river. I clutched my vase and my piece of wedding cake a little more tightly and hung on.

We crossed at a point where two rivers met a mile-long traverse over rock, boulders and sand. Now the waggon stumbled forward into old watercourses and laboured up the other side. We creaked and crawled, then lurched forward again. I began to wonder when we would come to the river.

On a strip of sand to the right I watched a lonely brown and black bird limping patiently about. Whats that bird? I called to Ron.

A paradise drake, he said.

Its lame.

Yes, probably been caught in a rabbit trap. He pointed to a matagouri flat ahead and to the right of us. Theres a rabbitter camped over there.

Halfway across the riverbed I saw it, the dreaded Wilberforce. It was split into two streams, each about fifty yards wide. I had hardly time to wonder how deep they would be before the leaders pulled down into the first of them and I was pleasantly surprised to see that the water barely came up to their knees.

The waters of the Wilberforce were locked up for the winter in the heavy matrices of snow and ice that rested on the mountains. Months later I was to see it with the spring thaw on its back brown, ugly and raging, a killer river that no man in his senses would cross. Now it was a gentle murmuring stream.

On the other side the road climbed gradually uphill in a series of twists and bends, following the course of the Rakaia above where it forked with the Wilberforce. There was a primitive beauty in this country. Everywhere I looked there were glistening, snow-covered mountains rising at angles not quite credible to eyes more used to the plains. Their whiteness was harshly slashed here and there by rivers which wound round their feet and seemed to slither through deep gorges as if the steep rock might try to deny them passage. A wild, unfettered quality in my surroundings combined with my excitement about a new and different life to sharpen my vision and perceptions.

As the waggon grumbled its way slowly nearer the mountains, the sun dipped behind their jagged outlines and dark shadows blotted the lower hills. The cold, which I had hardly noticed before, became intense. After its passage across the Southern Alps the wind breathed ice on us. My cheeks blenched from it, and I realised I was losing consciousness of my feet.

Is it far now? I asked.

Old Jim cracked his whip and the horses stepped out smartly for a few chains, then dropped back to their steady plod. As we came to each corner I could see another one farther on. The bends seemed never-ending in their sameness, and though each opened up some new vista my enthusiasm subsided as the cold laid greater claims to my body.

Is it far now?

My life lately seemed to have been mainly a struggle to keep warm. Ron and I had been married in the little church at Whitecliffs on a wintry Saturday afternoon five days before. Someone had remembered that nobody had brought any confetti, so our guests had gone to the village store across from the church, bought up the entire stock of rice, and pelted us with it. Almost congealed with the cold, for the church had been unheated, the exercise of trying to dodge the onslaught had not been wholly unwelcome. The wedding feast and the good wishes of our friends and relations had warmed us further, and wed set out for our honeymoon in Christchurch feeling more friendly towards the season and its winds. But when we arrived at our hotel, after a forty-two mile drive, I was again frozen to the marrow, and Ron, who had seemed so happy and full of assurance a few short hours before, had sat gloomily in the lounge with his pipe held firmly in his mouth, staring fixedly at the roses on the wallpaper.

The next day, a Sunday, the town had been as quiet and lifeless as a graveyard. Wed spent the day strolling the dim, foggy streets window shopping. There was no fire at the hotel and walking the streets was a degree or two warmer than sitting in the dank cold of the lounge gazing at the wallpaper. The next morning dawned colder still, if that were possible. Id looked out of the window at the bleak, damp street below and come to a sudden decision.