Diversion Books

A Division of Diversion Publishing Corp.

443 Park Avenue South, Suite 1004

New York, New York 10016

www.DiversionBooks.com

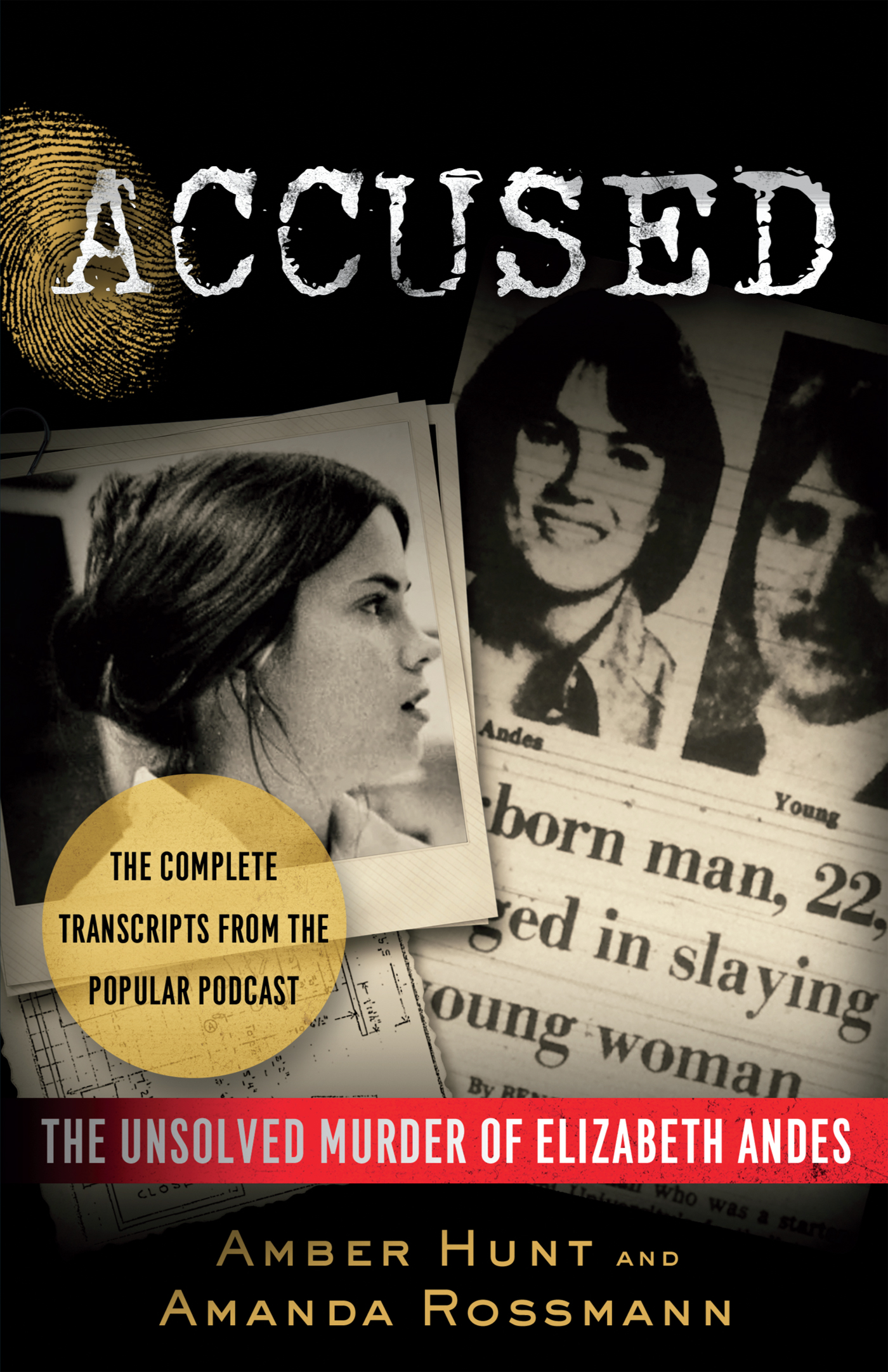

Copyright 2018 by Amber Hunt and Amanda Rossmann

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever.

For more information, email

First Diversion Books edition September 2018.

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-63576-454-3

eBook ISBN: 978-1-63576-453-6

LSIDB/1809

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

IVE NEVER BEEN ONE TO think things happen for a reason. Its too tidy a mentality, too dismissive of the dead.

My cousin, Natalie, died when we were seven. It haunted me until it inspired me, and, through that experience, I can assign it reason. But Im still unable to think of any cosmic justification for a sweet and precocious seven-year-old to take her last breath. We werent even given a solid cause. Reyes Syndrome, the pathologist guessed, pointing to the mysterious disease that swells kids brains and livers. My introduction to mortality was presented with a shrug.

So when Elizabeth Andess case landed on my desk, I wasnt open to the notion that it landed there with purpose.

Instead, I tallied the coincidences.

Beth, as her friends called her, was killed just a few months after I was born in 1978. She died in an apartment for which she signed the lease on my actual date of birth. Her case stagnated for decades, and then happened to come to me at the exact right time. I had written true crime books by then and knew how to organize hefty research. More than that, I had a new boss who trusted me and who was willing to take bold risks, and I had an editor willing to lobby on my behalf for extra time. I was even assigned a partner, Amanda Rossmann, with whom I immediately clicked.

Its hard to explain to nonjournalists how rare this confluence is. Newsrooms today are decimated; that part, everyone knows. What you dont see are the internal struggles. Ive been a reporter for more than twenty years. In the past five, Id started leaving more and more meetings near tears when bosses put too much emphasis on metrics and clicks and too little on the idealistic reasons I became a journalist. Thats not to say the emphasis wasnt warranted. Newsrooms are decimated because we need readers, and we measure readers these days with clicks. Editors and publishers have to worry about numbers. But most people who become journalists do it to change the world. We work long hours for lousy pay because we feed off the idea that truth matters, that we can make a difference by shedding light on stories that would otherwise remain shrouded. Our motivation isnt on what sells; its on what matters.

For those of us who took on her story, Beth matters. She did from the very first day.

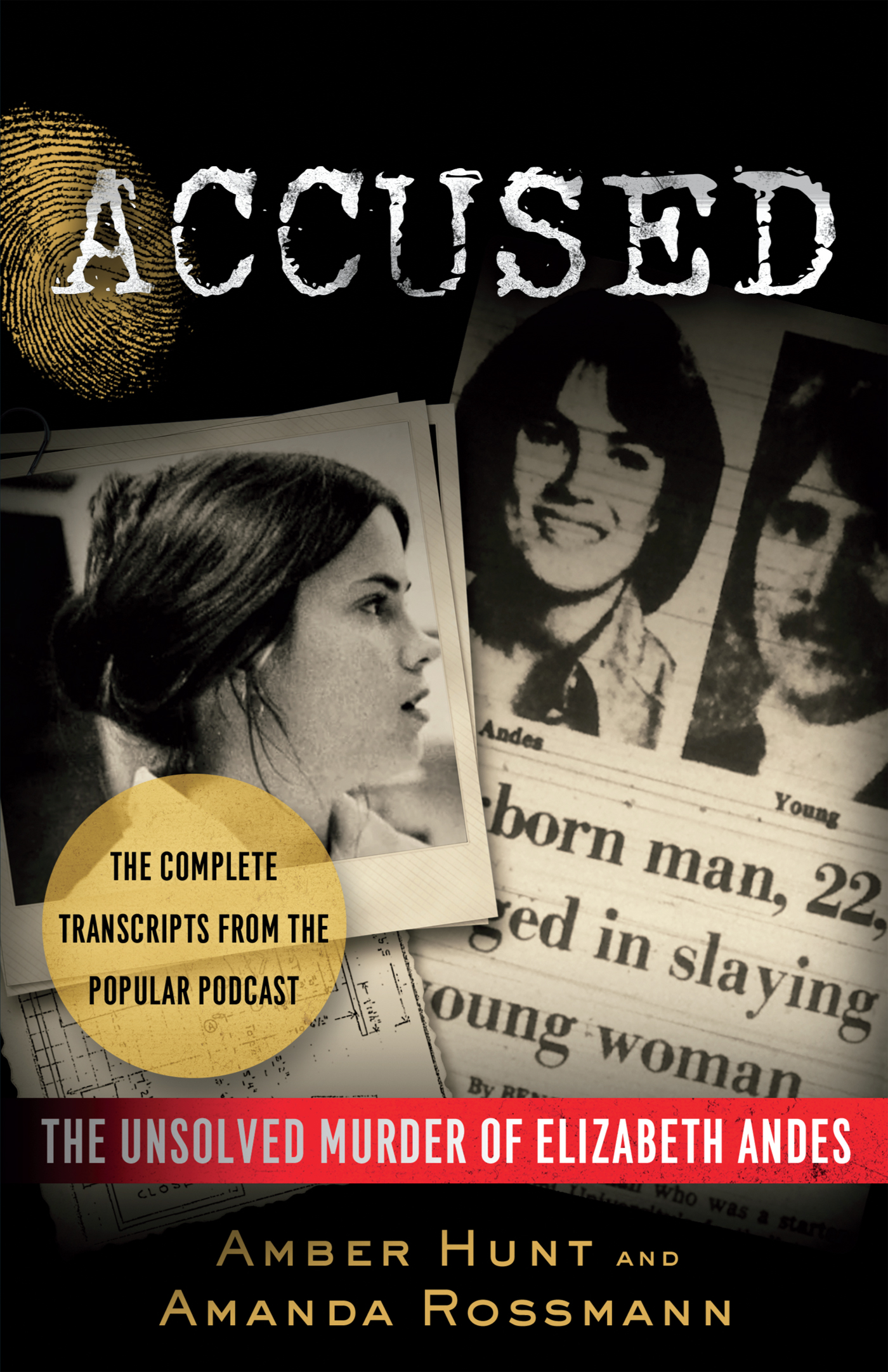

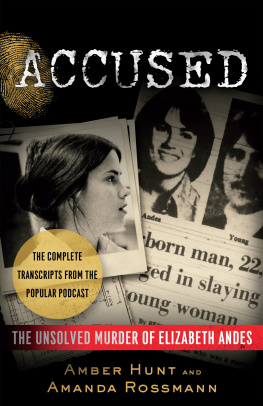

To hammer that home, we hung her picture front and center in the war room where we did the bulk of our years worth of investigation into her case. I describe the picture in the first episode of Accused , the transcripts for which are between these covers. Two years after that episode debuted, I still have that picture on my phone. I see Beth nearly daily. I think of her even more frequently.

Ive covered a lot of murders, and some are equally haunting. Beth is no more important than any other victim of the nearly 200,000 murders that remain unsolved in America. Each was someones daughter or son, someones friend, someones lover. But what struck me most about this case was how solvable it appeared. There were so many avenues overlooked by detectives, so much ego clouding their judgment. When youre tasked with solving crimes, you cant put blinders on to all the possibilities. You cant allow your theory to become the only one youll consider.

That might be why more journalists find themselves sleuthing these days, as evidenced by podcasts like ours. Journalists are trained to assume we dont know the answer. Were trained to question even ourselves. No human is without bias, and every good journalist I know makes an effort to know their biases and work against them. Every single story we tackle must be written with the assumption that someone has made a mistake. If your mother says she loves you, check it out. Theres a reason thats our adage. We never take any piece of information for granted.

Amy Wilson and Peter Bhatiamy boss and my bosss boss, respectivelyare some of the purest-hearted journalists Ive ever met. Without them, this project would never have happened. Peter walked into the Cincinnati Enquirer s newsroom in the spring of 2015 and announced that he was shifting the newsgatherers focus away from numbers. Instead, wed concentrate on the journalism. It might seem like a matter of semantics, but for most journalists, this is the shift in thinking we need to find the energy to get out of bed in the morning. Journalists get a bad rap these days, and Im quick to criticize those who slant their stories and resort to scaremongering. Not everyone who self-applies the journalist badge actually is one. But most of us, fallible though we all are, are simply overgrown, status quo bucking teenagers who need to believe we can make a difference. Peter gave us permission to try.

Amy went to bat for me every time my vision for Beths story changed. First, I thought itd be a print story. Then, maybe a series. When the scope of the investigatory ineptitude became clear and my vision morphed into a podcast, she had no reason to trust I could pull it off. Id barely done a radio interview, much less report outright for audio. Still, she trusted me, and Peter agreed. Go for it, they said. Do good journalism.

I couldnt have done so without Amanda. Whenever my energy would flag, shed be there with a new theory to perk me back up. I can be pragmatic, quick to consider statistics and likelihood. Shes got a conspiracy theory streak in her, and thats important when youre trying to keep an open mind. Anything is possible, after all. Statistics arent laws.

We started our investigation with a packet compiled by Deb Lydon, one of the most dedicated lawyers Ive ever seen at work. Lydon does believe things happen for a reason. Shes driven to help this family, for no pay and no glory. Shes stayed up late, tracked down witnesses, and pulled one autopsy report after another in search of clues. She answers to what she deems the highest of callingswhen Amanda was feeling under the weather one day, she promised, without hesitation, to pray.

Lydon had already brought her research to the Oxford Police Department, which in turn had presented the case to the Vidocq Society, which is this volunteer group of crime-fighting experts that meets monthly in Philadelphia to evaluate cold cases and suggest new avenues of investigation. Despite that effort, police made no real progress on the case. The original suspectwho had decades earlier been acquitted by a jurywas not publicly cleared. Nothing was reported in the press. Lydon, frustrated by the stagnation, brought her research to the Enquirer .

Next page

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION