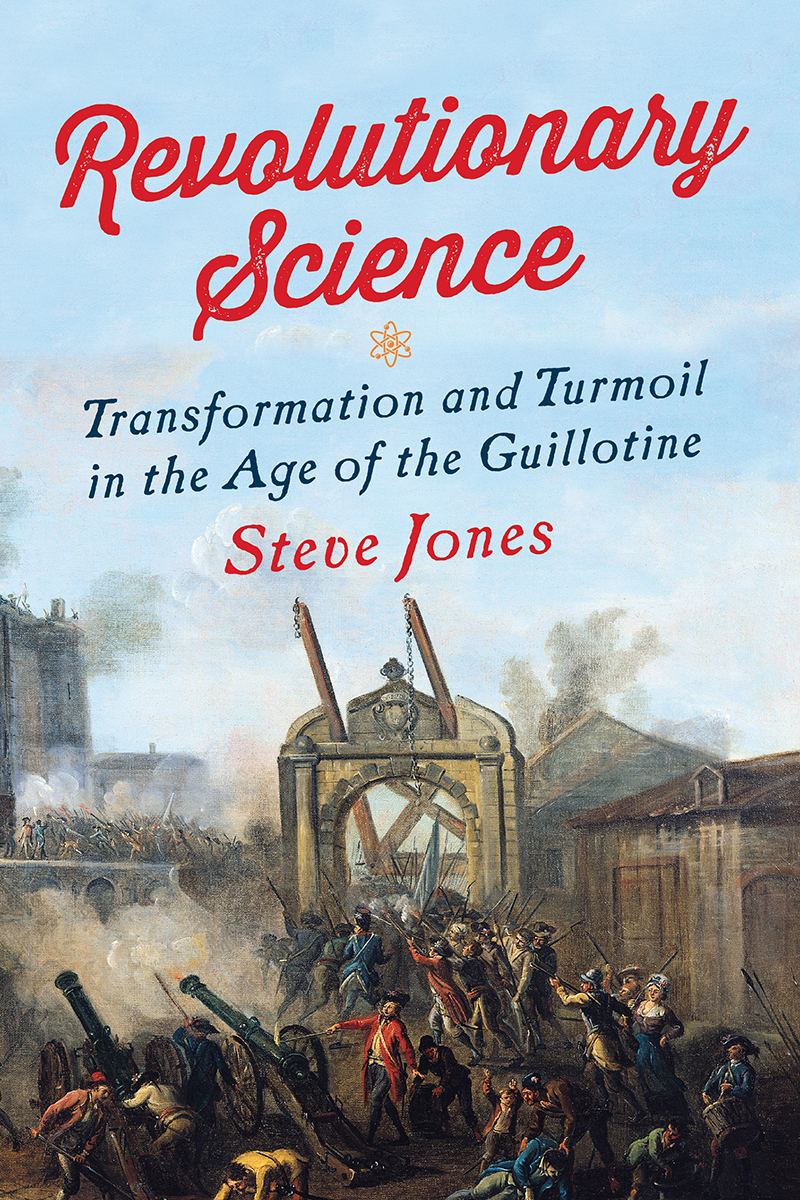

France, since the Reign of Terror hushed itself, has been a new France, awakened like a giant out of torpor.

THOMAS CARLYLE, The French Revolution

This book began with the Eiffel Tower, erected to celebrate the centennial of the French Revolution and now the universal symbol of France itself. Its elegance, and that of its native city, disguises the disasters and triumphs that the people of Paris suffered in the ten decades between the massacre on the Champ de Mars, the patch of parkland upon which the monument stands, and the towers own birth. That troubled era emerged in large part from what Gustave Eiffel called the great scientific movement of the end of the eighteenth century. Many of the most celebrated participants in that enterprise were active in the Revolution, and several died for their beliefs, but as the tide of revolutionary bloodshed receded, others were able to return to their research. In time, a solid portion of the survivors (some among them once fiery radicals) became senior figures in succeeding governments of a variety of flavours, often based on principles very distant from those of 1789.

The discoveries of those days are the foundation of much of modern physics, chemistry and biology. More important to the lives of the people of Paris they gave rise to an economic boom that transformed the French capital, for the labours of its researchers led to technologies that made the city for a time the most productive, and most polluted, industrial centre in the world.

The fuse of that economic explosion had been lit by Louis XIVs finance minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, who set up the system of central control that long pervaded French society, and French science. In 1666, the monarch, at Colberts suggestion, established the Acadmie Royale des Sciences. Unlike the Royal Society in London, the Acadmie was firmly defined to be an arm of government. It had a substantial income and was given a home in the Louvre.

From its earliest days its members were asked to deal with practical problems and its charter enjoined them not to waste their time only on curious researches or chemists amusements but instead to ensure that they acted in relation to service of the king and the State. As the years went by, more and more of their efforts were directed towards applied work. Its surveyors made the first accurate map of France, while its astronomers published the first dependable list of the positions of various celestial objects, a document essential for navigation. Its chemists discovered dozens of new compounds, many of practical value, and its physicists took the first steps towards todays electrical machinery. Academicians were also commanded to test new machines such as an apparatus to roll lead plate (some schemes, such as those for windmill-powered ploughs, and ships with springs to help them bounce off rocks, failed the examination). The Academys efforts to apply its members talents to commercial ends reached a peak in the half-century around the Revolution. In the 1760s, Ren Antoine de Reaumur, whose name is remembered for his temperature scale and who was also a metallurgist and an expert on insects, was ordered to produce an account of the useful arts. His own contribution was a document entitled The Art of Hatching and Bringing up Domestic Fowls by means of Artificial Heat, and he went on to edit an enormous multi-author work, the Descriptions des Arts et Mtiers, which ran to a hundred and thirteen folio volumes and took twenty-five years to complete. It remains the most extensive single publication on technology ever produced.

Its sections include an eleven-page pamphlet on how to make starch and a thousand-page tome on coal-mining. On the way, it deals with glue, carpets, lamps, soap, locks, charcoal, bricks, noodles, felt, sugar, ironware and fish. Many eminent figures offered their expertise, often on unexpected topics. The astronomer Jrme Lalande, better remembered for his work on the transit of Venus, wrote nine of the treatises, those on cardboard, parchment and leather included, while the huge volume on mining was penned by Jean-Franois-Clment Morand, an expert on the thymus gland.

The revolutionary government fostered technology in many other ways. First, it modernised the patent system. Every invention should be the property of its originator and could be protected for fifteen years on payment of the appropriate fee. The guilds that had controlled the numbers allowed into each trade were abolished, on the grounds that every citizen had equal rights to practise any profession. Innovation was stimulated with an expanded system of prizes offered for useful ideas (and Lavoisier himself had launched his career with an award for his plan for improved street lighting). The first message sent by semaphore telegraph by its French inventor, who had done the job with the help of such a subvention, was The National Assembly will reward experiments which are useful to the public (a rival scheme, which involved a cannonball armed with a message and fired from one artillery battery to the next until it reached its destination did not, like the spring-loaded ships, find favour). Almost three hundred such grants were made, for schemes as various as a method for filling hydrogen balloons and a new dye for hats. Under Napoleon the system expanded and became the Socit dEncouragement pour lIndustrie Nationale, itself provided with a substantial subsidy and run by a consortium of scientists and bankers.

Frances researchers, unlike their more fastidious British equivalents, were happy to become involved in industry. They joined with enthusiasm in their rulers attempts to direct the course of economic progress, and became keen instruments of the dirigisme (tellingly, a word that has no precise English translation) that marked the nation.

The republican administration in its first days lit the bonfire of the vanities of the Ancien Rgime, many of whose laws and regulations were swept away. Whatever the faults (and there were plenty) of the royalist establishment it had at least imposed some planning rules on its capital: factories that produced lead-based paints and pigments were banned from the centre, as were the smoky furnaces used to make plaster of Paris, while the manufacture of tripe was confined to the le des Cygnes, well downstream. After the collapse of that regime, and in part because of the urgent demands for military supplies, all such controls were removed. The populace paid the price.

The chemist Jean-Antoine Chaptal had discovered that wine sweetened with beet sugar was stronger and more palatable than the unadulterated stuff. He set up a network of factories to extract sugar from beets, and established others that made white lead (used in paint), together with acids of various kinds. Under Napoleon, Chaptal became Minister of the Interior. He soon saw to it that all remaining restrictions on industry in residential areas were struck off the books.

Within a couple of decades of the Revolution, the City of Light was besmirched. It became, like many lesser places, a centre of the chemical industry: a sordid, ugly town. The sky is a low-hanging roof of smeary smoke and the atmosphere is a blend of railway tunnel, hospital ward, gasworks and open sewer. The features of the place are chimneys, furnaces, steam jets, smoke clouds. The products are pills, coals, glass, chemicals, cripples, millionaires and paupers. That is in fact a nineteenth-century description of St Helens in Lancashire, but just the same, if not worse, could be said of contemporary Paris.

By 1801, the French capital contained three thousand factories, many among them based on the discoveries of Lavoisier and his followers. They poisoned the air and the water, and contaminated the streets. Household waste was boiled down for its fat, gelatin and starch, the raw materials of various chemical processes. Tan yards, soap-boiling plants, and vinegar distilleries with their vile stench sprang up next to schools and hospitals. Such enterprises were matched by many others.

Next page