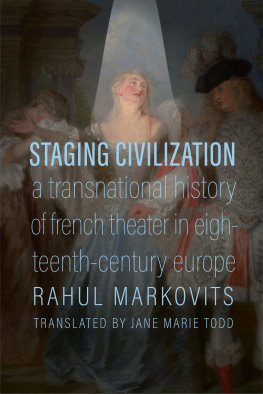

THE SMILE REVOLUTION IN EIGHTEENTH CENTURY PARIS

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox 2 6 dp ,

United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of

Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Colin Jones 2014

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2014

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in

a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the

prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted

by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics

rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the

above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the

address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013957963

ISBN 9780198715818

ebook ISBN 9780191024856

Printed in Great Britain by

Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and

for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials

contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

For Alec, Ethan, Jonah, Milo, Greta, and Rosa.

You make me smile.

Acknowledgements

I have been working on this topic for some years, and sometimes had the impression that the book at the end of the project was like the smile of Lewis Carrolls famous Cheshire cat, endlessly receding in and out of focus at the end of the trail. The advantage of working on such a topic over a lengthy period, however, is that I have constantly been able to add anecdotes, stories, and perspectives along the way, as relevant references cropped up in dispersed and often unlikely sources. Audiences at lectures, seminars, and around many dinner-tables and in numerous cafs and bars have invariably been drawn into the intrinsic interest of the topic and I thank them warmly for their numerous, fertile, and helpful suggestions. (Occasionally in return I have learnt more about a listeners dental problems than I would strictly have liked to hearthis is one of the oddities and indeed the charms of my subject.) As well as the assistance of friends and colleagues I would like to acknowledge the unfailingly kind and helpful staff of numerous archives, libraries, museums, and galleries consulted. So numerous have the individuals been who have helped in some way that I am simply unable to list them all. Let this be a token of thanks to those not mentioned here: I hope they realize how grateful I am.

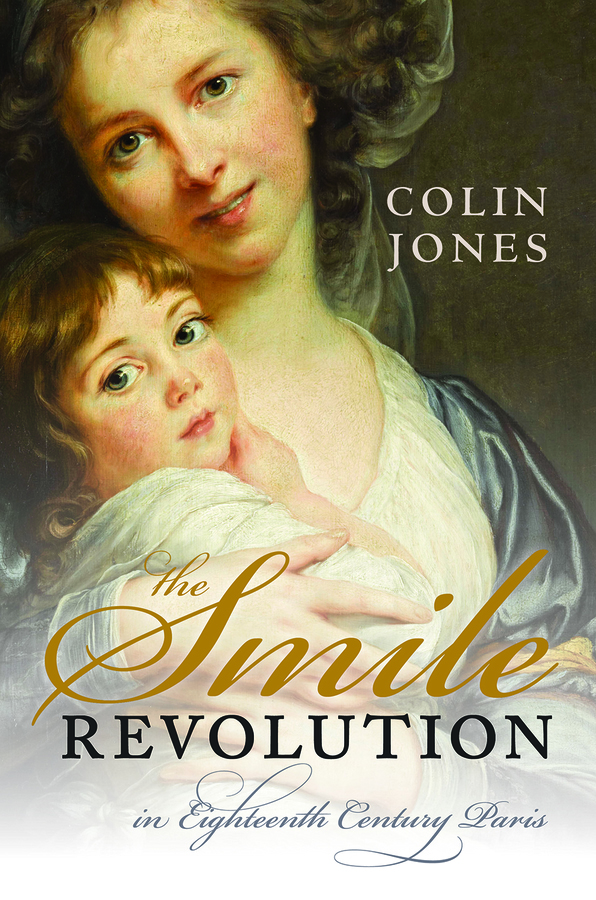

The idea behind the book sprang out of an exchange with Richard Wrigley, who told me about the painted smile of Madame Vige Le Brun just as I had been working on Parisian tooth-pullers. I immediately glimpsed the makings of a topic. I thank Richard warmly for his inspiration and his continued encouragement over the years. In the two universities which have employed me while I researched this topic I was fortunate to enjoy the company of scholars who, quite possibly without realizing it, offered more intellectual stimulation, inspiration, and camaraderie than any academic has a right to expect. In particular I thank Maxine Berg, Margot Finn, Sarah Hodges, Gwynne Lewis, Roger Magraw, Hilary Marland, Carolyn Steedman, Claudia Stein, Mathew Thomson, and Stephane Van Damme from Warwick University days; and at Queen Mary University of London, Richard Bourke, Thomas Dixon, Rhodri Hayward, Julian Jackson, Miri Rubin, Quentin Skinner, Amanda Vickery, and the History of the Emotions group. In Paris, Daniel Roche and Jean-Jacques Courtine have offered unfailing inspiration and support. I also wish to acknowledge the Leverhulme Trust for a research network grant to explore the history of physiognomy and facial expression. My fellow organizers on the projectNadeije Laneyrie-Dagen, Lina Bolzoni, Thomas Kirchner and Martial Guedroncomprised a brilliant group within which to develop my ideas.

I am also particularly grateful to those friends and colleaguesEmma Barker, Thomas Dixon, Roger King, Melissa Percival, Richard Taws, Charles Waltonwho kindly read an earlier version of the manuscript and offered insightful suggestions for improvements. So did my friend Michael Sonenscher: for the last forty years, I now realize, he has helped me with his advice whenever I needed a steadying intellectual hand. My debt to him is very great. I am also very fortunate in having the inimitable Felicity Bryan as my agent, and the help and encouragement that she and her team, particularly Michele Topham and Jackie Head, provide. I also thank the staff at Oxford University Press for their help throughout the publishing process and my copy-editor Jeremy Langworthy.

I am a mildly obsessive writer and rewriter. I am aware that, though since transformed, some of the ideas in the book overlap with earlier writings published elsewhere. These include French Dentists and English Teeth in the Long Eighteenth Century, in John Pickstone et al. (eds.), Medicine, Madness and Social History: Essays in Memory of Roy Porter (Basingstoke, 2007), pp. 7389, 24750; Bouche et dents dans lEncyclopdie: une perspective sur l'anatomie et la chirurgie des Lumires, in R. Morrissey and P. Roger (eds.), LEncyclopdie: du rseau au livre et du livre au rseau (Paris, 2001), pp. 7391; Pulling Teeth in Eighteenth-century Paris, Past and Present, 166 (2000), pp. 10045; and The Kings Two Teeth, History Workshop Journal, 65 (2008), pp. 7995. The topic is also touched on lightly in my Presidential Lectures for the Royal Historical Society, in particular French Crossings II: Laughing over Boundaries, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 21 (2011), pp. 338, and French Crossings III: The Smile of the Tiger, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 22 (2012), pp. 335.

Towards the end of completing the manuscript, I accepted a kind invitation from Simon Chaplin and Quentin Skinner to give a paper recapitulating some of my arguments as the Roy Porter Lecture at the Wellcome Library in London in 2012. I have always felt that the book would be written with the spirit of Roy Porter hovering over it and I am sad he is not around to read it.

Finally, my greatest debt is to my wife Josephine McDonagh for just about everything in the making of this book. She has been by my side or in my thoughts throughout the researching and writing. The book is dedicated with much love and indeed many smiles to our grandchildren.

Contents

In the autumn of 1787, the celebrated painter Madame lisabeth-Louise Vige Le Brun displayed a self-portrait at the Paris Salon, the biennial art exhibition held in the Louvre which was renowned for setting the standards of Parisian and European taste. She portrayed herself dandling her daughter on her lap, and with her own mouth set into a pleasing smile, her lips parting to reveal white teeth ().