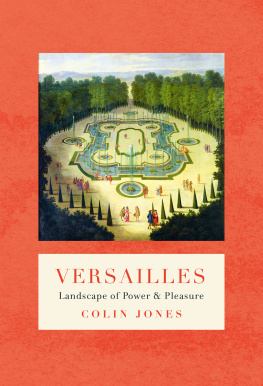

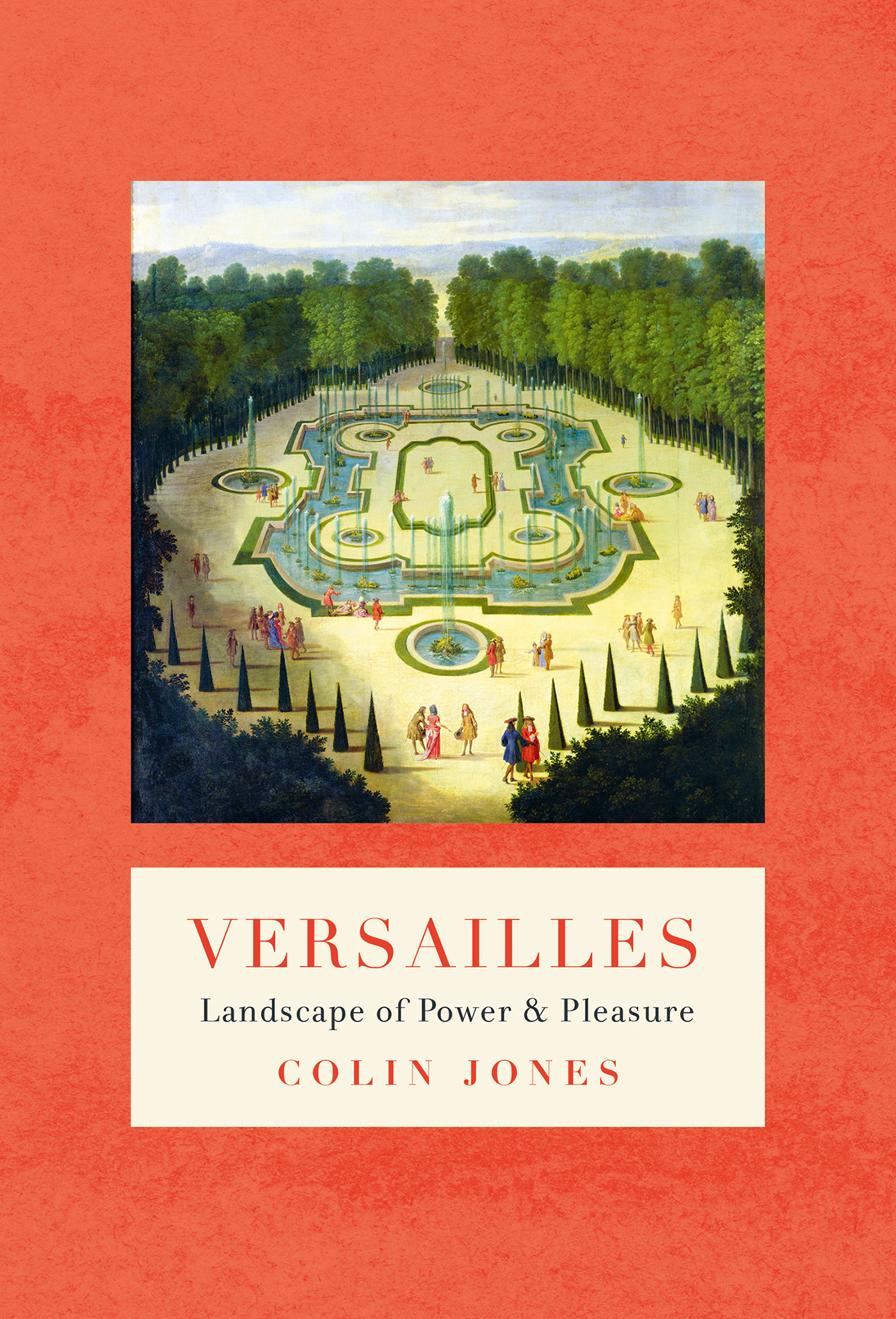

VERSAILLES

Landscape of Power and Pleasure

Colin Jones

AN APOLLO BOOK

www.headofzeus.com

Few buildings carry such a freight of historical symbolism as the Palace of Versailles. First built as a hunting lodge by Louis XIII in the early seventeenth century, then radically repurposed by his absolutist son Louis XIV, Versailles became the focus of that kings centralized power.

Drawing on a new wave of research in recent years, particularly on the construction and material culture of Versailles, Colin Jones describes the building campaigns undertaken by Louis XIV and his formal installation of the royal court; the changing fortunes of the palace from the Revolutionary and Napoleonic era through to the Second Empire; its return to the political stage in the Franco-Prussian War; its later role as a venue for treaty signings and state occasions; and its continuing legacy as an epochal and world-historic site of cultural memory.

Contents

The garden faade of the central body of the chteau, 166884

Chteau de Versailles, France/Bridgeman Images

The king had hardly said that there should be a palace than a wondrous palace emerged from the earth

This sounds like a fairy tale and indeed the words are those of Charles Perrault, the author of Little Red Riding-Hood, Cinderella, Puss in Boots and many other classic fairy stories. The creation of the Palace of Versailles, to which he was referring, was not quite as instantaneous as a fairy tale might require. But it was not far off. For within a matter of years after 1660, an obscure hunting lodge was transformed into a huge and magnificent set of buildings, commandingly placed in ornate gardens. For posterity, as much as for his contemporaries in France and across Europe, Versailles redefined what a royal palace should be.

The claim that all this was the work of a single man Perraults master, in fact was exaggerated, but it was not mere flattery by a sycophantic courtier. The Bourbon king Louis XIV (ruled 16431715), absolute monarch and ruler by divine right, selected the location (of which his father Louis XIII had been fond), conceptualised the kind of palace he wanted built and, for decades right up to the moment of his death devoted all his imaginative powers to its realisation. Versailles was the considered brainchild of a king who wanted a monument that could glorify, commemorate, inspire and command. Created on royal orders, constructed and decorated to royal-approved design, the palace was made at a gallop to the measure of a single man, who flaunted himself to his courtiers and his subjects as Louis the Great.

As the author of fairy tales suggested, this enchanted site functioned through sheer dazzlement. Scale and beauty worked in tandem to compel respectful awe from all who encountered it courtiers, noblemen, diplomats, travellers, merchants and artisans, and ordinary Frenchmen and women. The greatest artists in French history were tasked to produce an overwhelming decorative spectacle. The project extended beyond the walls of the palace, for Louis also took an obsessive interest in its gardens; and a thriving new town was conjured out of a tiny adjacent village. Versailles was not just a power-building: it comprised a whole landscape of power. There was a cosmic dimension to it too: one of the principal allegorical motifs of power woven into the palaces fabric was the image of Louis as the Sun King, le Roi soleil, benignly radiating the warmth of his influence over his subjects, as the universe revolved around him.

Louis XIV by Hyacinthe Rigaud, 1701, was commissioned as a gift to Louiss grandson but the king admired it too much to let it go and placed it in the state apartments on public view.

The Louvre Museum, Paris

This characteristic boiserie incorporates at its centre Louis XIVs sun motif.

Chteau de Versailles, France/Bridgeman Images

The prestige of Versailles was at its zenith after 1682, when Louis moved his whole court to the site. He brought his government bureaucracy in tow as well, effectively turning his back on Paris, the largest and most prestigious city in continental Europe. Versailles was henceforth in substance the French monarchys court, capital and seat of government.

Only the king of the greatest and richest power in Europe could have possibly imagined (and resourced) a scheme as majestic, as ambitious and as demanding as Versailles. Its prestige grew exponentially as the eighteenth century unfolded: the palace stimulated fellow monarchs across Europe into emulation; its grounds exemplified the French garden style, whose popularity swept Europe; and even the town of Versailles, in effect a Louis-Quatorzian creation with its wide straight roads, provided a model that prefigured Haussmanns nineteenth-century redevelopment of Paris and, more immediately, inspired Washington in the United States and Portugals post-earthquake Lisbon.

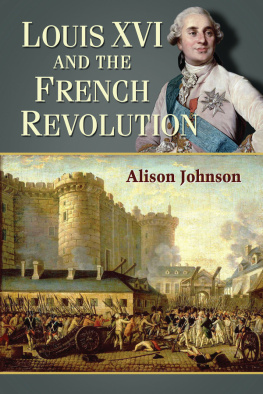

Yet the Versailles project put severe strains on Louis XIVs treasury and placed his successors, Louis XV (ruled 171574) and Louis XVI (ruled 177492), in a paradoxical situation. Neither wanted to change what seemed to be the winning Louis-Quatorzian formula for greatness, based on displays of power abroad as well as at home. Yet the task of living up to their predecessors standards was challenging, and neither monarch found Louis XIV easy to imitate. To some extent they could only become themselves by diverging in certain ways from the Louis-Quatorzian ideal. This was even more the case for Louis XVIs queen, Marie Antoinette, who loved the palaces splendour but wanted it to be focused mainly on herself. Increasing public unease echoing a Black Legend that went back to Louis XIVs ruinous wars and his repression of Protestantism highlighted the glaring contrasts between the luxury of the court and the living conditions of the rest of the nation. By 1789 Versailles had become a national bone of contention rather than a symbol of unity under the Bourbon dynasty.

There were thus already questions in the air about the role of Versailles in the political system prior to the French Revolution, when the French monarchy descended swiftly into a terminal crisis. From the declaration of the First Republic (17921804) onwards, it was asked whether a palace complex made to measure for the greatest monarch in early modern Europe could be accommodated within a modernised political system. Could Versailles be de-Bourbonised? And what exactly was Versailles for in a post-absolutist age? Successive governments including Napoleon, whose empire (180414) followed the demise of the First Republic, and a restored Bourbon monarchy between 1815 and 1830 grappled with this conundrum, but failed to supply a durable answer in what was a highly volatile political atmosphere.