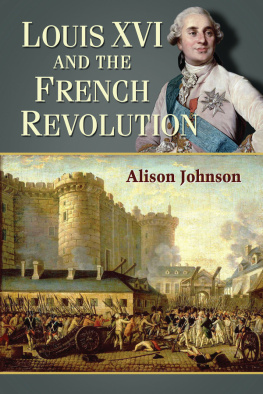

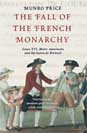

Louis XVI and the French Revolution

ALISON JOHNSON

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina, and London

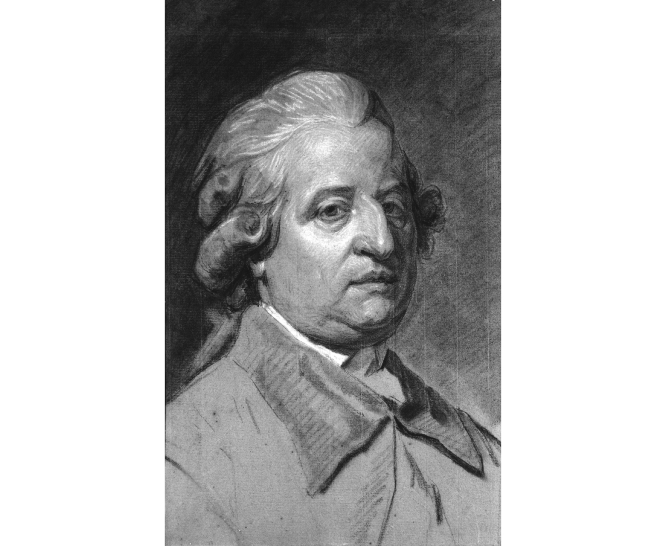

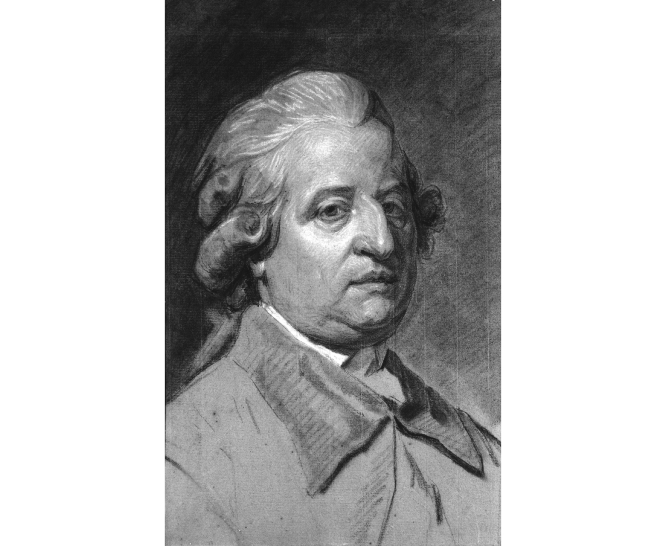

Joseph Ducreux (17351802) portrait of Louis XVI. Paris, muse Carnavalet. Muse Carnavalet/Roger-Viollet/The Image Works.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-0243-1

2013 Alison Johnson. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any formor by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopyingor recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system,without permission in writing from the publisher.

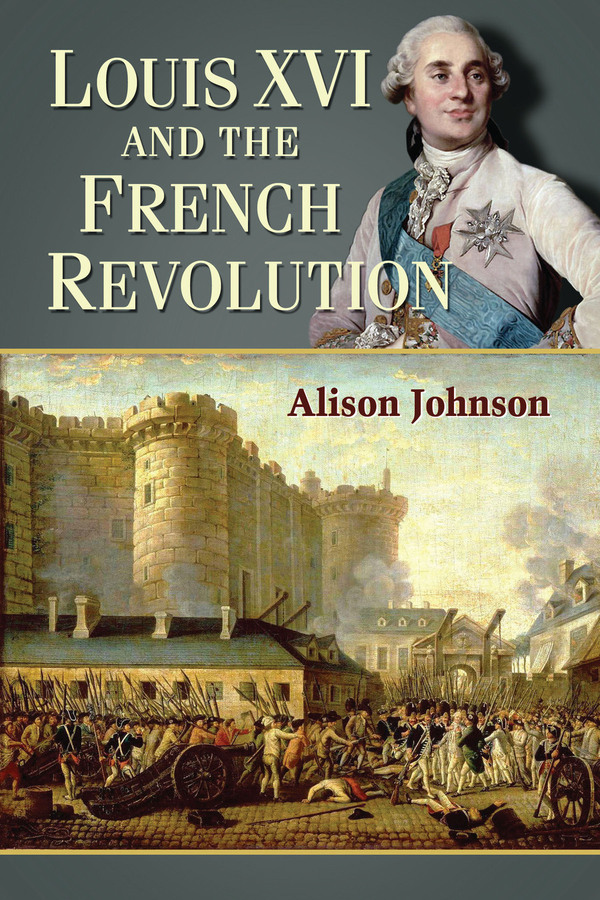

On the cover: Joseph-Siffred Duplessis, Portrait of Louis XVI, King of France and Navarre, 1776. Oil on canvas, 31.5" 24.4". Storming of the Bastille and Arrest of the Governor M. de Launay, July 14, 1789 (artist and date unknown). Oil on canvas, 22.8" 28.7".

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To my mother and father

Preface

A weak king. The phrase echoes across two centuries to condemn the man who happened to be king when the French Revolution erupted. Those who admire the Napoleons of history will nd little to interest them in the character of Louis XVI, a gentle man whose abhorrence of bloodshed and refusal to use military force against his opponents contributed to the loss of his throne.

Louis XVI may have been a weak monarch, but his personal courage was undeniable. On the day the Bastille fell the mob murdered two of his ofcials and paraded their heads through the streets of Paris on pikes, but only a few days later Louis XVI rode from Versailles to Paris with no protection to meet with the insurgents. During the rst invasion of the Tuileries Palace three years later, he faced armed assassins only a few feet away with uninching resolve and refused to capitulate to their demands for the deportation of priests unwilling to break with Rome.

Louis XVI did not want to be king. A quiet life spent in pursuit of his interests in locksmithing, carpentry, and geography would have been more to his taste than the luxury and intrigues of Versailles. He accepted the responsibility to rule, however, and attempted to work for the welfare of his people until his government was engulfed by the violent upheavals of the Revolution. Perplexed by the course chosen by so many of his subjects, Louis XVI hesitantly gave way, step by step, to the policies they demanded. Few rulers have acquiesced in such startling changes of government within such a brief span of time as Louis XVI.

Louis XVI remains above all else a very private man. Except for a handful of ofcial letters, he left almost no record of his thoughts and feelings. We get a clear impression of him as a person only at the end of his life through the sensitive record left by the valet who served him in the months he was imprisoned before he was guillotined. During this same period an artist painted a portrait that shows the haunting face of a man who has suffered, contrasting sharply with the impassive and impenetrable visage in the ofcial portraits painted earlier in his reign.

Perhaps no one has offered a more sensitive appraisal of Louis XVI than Malesherbes, a leading liberal intellectual who served him as minister:

He is a worthy prince ... but in certain situations ... the qualities that are virtues in a private citizen become almost vices in a person who occupies the throne; they may be good for the other world, but they are worth nothing in this one.

In her book The Deaths of Louis XVI: Regicide and the French Political Imagination, Susan Dunn introduces her chapter on Albert Camuss reaction to the execution of Louis XVI in this way:

A few years after the liberation of France, a war-weary Albert Camus, facing new cold war realities, looked back at the execution of Louis XVI and termed it the most signicant and tragic event in French history, a turning point that marked the irrevocable destruction of a world that, for a thousand years, had embraced a sacred order. Celebrated by some as mans seizing control of his political and historical fate, the regicide was mourned by others like Camus as the permanent loss of a moral code sanctied by a transcendent God.

Camuss book The Rebel: An Essay on Man in Revolt contains a chapter titled The Regicides that includes this key passage:

On January 21, with the murder of the King-priest, was consummated what has signicantly been called the passion of Louis XVI. It is certainly a crying scandal that the assassination of a weak but goodhearted man has been presented as a great moment in French history.

In this biography I have chosen to focus primarily on those parts of Louis XVIs life that will help the reader to understand this unassuming man who found himself at the center of one of the most pivotal moments of history. I do not dwell at length upon the complex economic and political causes of the Revolution, which have been covered in great detail during the last two centuries, with nothing close to a consensus being reached. As Bailey Stone noted in his 2002 book Reinterpreting the French Revolution:

The Bicentennial of the French Revolution may have given rise to a ood of commemorative activities, but it has not left in its wake any scholarly consensus on the causation, development, and implications of that vast upheaval. To the contrary, historians barely nished with the pleasurable work of interring a Marxist view of the Revolution regnant in the rst half of the twentieth century have turned their spades upon each other, all the while trying to establish their own explanations of cataclysmic events in the France of 178999.

Fortunately for posterity, many highly intelligent observers who found themselves at the center of the Revolutionary period kept detailed journals that were printed in the late 1790s and early 1800s. Most of these are now available online in French, and English translations are also available online in some cases. In many sections of this biography, I have chosen to quote extensively from these works that are now in the public domain because they give an immediacy and accuracy that paraphrasing cannot convey. I have provided my own translations.

Another source of primary documents that I used heavily is the very large Arneth collection of correspondence in the Austrian archives between Maria Theresa, the Austrian empress, and her daughter Marie Antoinette, as well as the correspondence between Maria Theresa and her ambassador to France, who was guiding Marie Antoinette in her role as the dauphine and then the queen of France. As Derek Beales points out in his biography of Joseph II (son of Maria Theresa and brother of Marie Antoinette), a bogus collection of letters involving these Austrian principals was published in 1790. According to Beales: Of the forty-nine letters it contains probably only seven derived from genuine originals. Almost all the remainder are demonstrably pure inventions. As Beales notes, Saul Padover quoted widely from these forged letters in his 1939 biography of Louis XVI, and many other authors then quoted them from Padovers biography. My minimal use of secondary sources helps reduce this kind of error.

Next page