Will Bashor received his MA in French literature from Ohio University and his PhD in international relations from the American Graduate School in Paris. From Columbus, Ohio, he now lives in Sitges, Spain. A member of the Society for French Historical Studies, he specializes in eighteenth-century French literature, culture, and history. His most recent work was Marie Antoinettes Darkest Days: Prisoner No. 280 in the Conciergerie, which traced the fallen queens last seventy-six days in the waiting room for the guillotine. Other publications include Marie Antoinettes Head: The Royal Hairdresser, the Queen, and the Revolution, which won the Adele Mellen Prize for Distinguished Scholarship and was a New York Post Must-Read book in 2015, and Jean-Baptiste Clry: Eyewitness to Louis XVI and Marie Antoinettes Nightmare. Visit him at www.willbashor.com.

T here are a number of people I must thank for their help with guiding this project. First, I must express my gratitude to the staff at Rowman & Littlefield and especially my editors, Susan McEachern and Katelyn Turner, whose patience and invaluable advice were exemplary. Also, Janice Braunstein, the books project editor, and Chloe Batch, the cover designer, have contributed so skillfully to make this book possible.

Second, I can never forget the supportive staffs at the libraries and archives I visited while researching and writing this book, including the National Archives and the National Library of France, the Ohio State University Library, and the National Archives of Sweden. It is also with the deepest gratitude that I acknowledge the handwriting analysis by Marie Antoinettes graphologist, Bella Choji; the expert assistance for her natal chart from the Astrology House New Zealand; and the invaluable assistance in French from Stphane Gagnon and Jean-Franois Robichon.

Finally, recognition must go to my family, who has always supported and encouraged me, even though the miles between us were many at times. It saddens me that my mother and grandmother cannot see this bookthey would have been so proud. My brother, however, remains a constant source of inspiration, and this book is lovingly dedicated to him.

If it can happen that we feel thirsty and yet do not wish to drink, there must be something in our psyche that bids us drink, and something else that forbids it. The latter is reasoning or the calculating part of the soul; the former is the passionate.

Plato, The Republic

F or more than two centuries, historians have contemplated the psyche of Marie Antoinette, the iconic queen of novels, biographies, and the silver screen, who graced the halls of Versailles until her life was ended by the guillotines blade.

In my previous works, I charted Marie Antoinettes life as seen through the eyes of her servants and jailers to present an unbiased account of the life of the last queen of France; however, in doing so, I neglected to delve into what historian Pierre de Nolhac called the so little-known intimate life of the royal family. In this work, therefore, I attempt to present a more exhaustive picture of the queens world, ranging from an analysis of her handwriting to an emotional genealogy of more than four generations.

Readers who are familiar with my previous objective stance regarding the queen will find it absent from this book. In contrast to many of Marie Antoinettes biographers, I cannot blindly assume her innocent of sexual promiscuity based solely on the lack of any hard evidence against her, especially in light of the numerous alleged affairs and licentious acts that scandalized her realm at the Chteau of Versailles. Put bluntly, Marie Antoinettes world cannot be styled as anything but conducive to intrigue, infidelity, adultery, and possibly, sexually transmitted disease.

Marie Antoinettes often thoughtless, fantasy-driven, and notorious antics have shown that there was indeed something in her psyche that bade her, in Platos words, to drink, especially amid the self-indulgent entourage of her court.

In response to those who may accuse me of dishonoring the sacred memory of Marie Antoinette, I contend that I honor her more by depicting a real woman rather than a martyred queen of the French Revolution. And more important, am I not honoring her even more by placing blame where it belongson the influence of those in her circle, the vile environment of the court of Versailles, and on the sins of her fathers?

Protecting the queens privacy should not be an excuse for sweeping unpleasant details of her life under the royal carpet. Readers will thus have the task of weighing all the evidence presented here, and because some evidence is stronger than others, it will also be their task to decide whether this new characterization of the last queen of France can be justifiedbeyond any reasonable doubtas we peek behind the decorative screens, learn the secret language of the queens fan, and explore the secret passageways and staircases of endless intrigue at Versailles.

I am going to Versailles tomorrow for two or three days... anywhere as long as I am far from these women.

Louis XIII, August 19, 1638

T welve miles from Paris, the country village of Versailles prospered in the Middle Ages, known then for its small castle, windmill, and church of Saint Julien. After the Hundred Years War, however, the castle fell into ruin in a sparsely populated area of marshy land, an area known locally for its stinking ponds. The ponds, some of which fed into each other, emptied into the Ru de Gally, a small river of sewer water widely said to be black as ink.

Henri IV regularly hunted in this area, bringing his six-year-old son Louis here for the first time on August 24, 1607. After Henris death in 1610 and by the time the child was crowned Louis XIII, the melancholic Louis found joy in returning here for riding and the hunt.

One day in February 1621, when hunting for stag ran later than usual, Louis found himself at nightfall on a small hill where an ancient windmill stood. He slept here on a bed of straw while his men took shelter in a nearby cabaret, and when he woke, the fresh air soothed his soul. Finding the mill uncomfortable, two years later, at the age of twenty-one, Louis decided to build his own pavilion with a small park attached, and the mason Nicolas Huaut began work on the site where the mill stood.

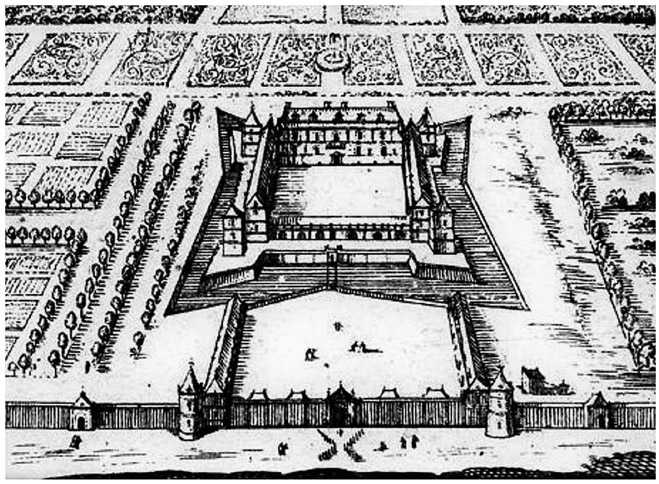

Dense woods and pestilent wastelands surrounded the original site where Louis XIII began construction to create his havena graceful, but small, castle that the Duke of Saint-Simon called a little pasteboard box. But Louis was content with the spot, which was neither too near nor too far from his court at Saint-Germain-en-Laye. Saint-Simon also called the kings country retreat a chteau of cards, and the Venetian ambassador called it una piccola casa per ricreazionea mere folly. A courtier named Bassompierre said one could not boast of it, but it was better than sleeping on a mattress of straw infected with fleas, ticks, and vermin.

When the king stayed at the pavilion, he had his bed brought from Paris. He stayed for only a night or a week at a time until 1630, when he would take up permanent residence after his overbearing mother, Marie de Mdicis, failed to displace Cardinal Richelieu as chief minister and succumbed to self-exile.

Louis XIIIs physician, Jean Hroard, wrote, Whenever the king arrived at Versailles, he hunted, dined, and afterwards went riding to take a deer or a fox. After supper, he would often exercise with his musketeers or create and perform ballets before retiring for the night. Before long, Versailles served as the kings treasured escape from his ministerial duties, his queen, and women in general.