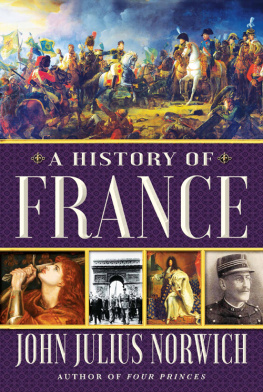

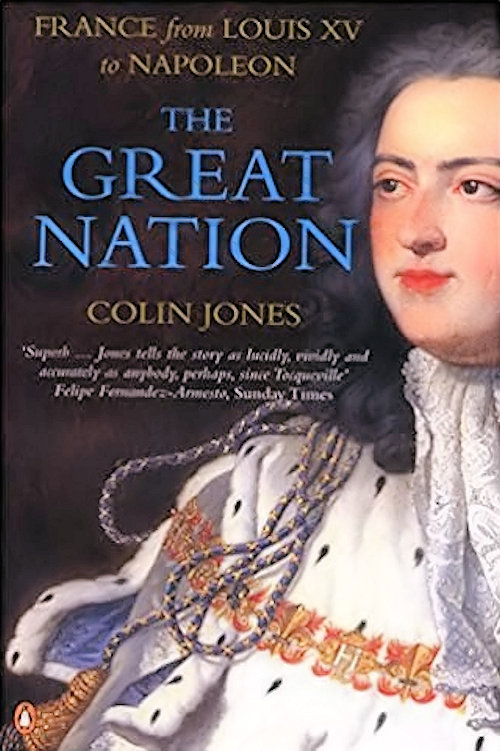

Colin Jones

THE GREAT NATION

France from Louis XV to Napoleon

PENGUIN BOOKS

THE GREAT NATION

Colin Jones is Professor of History at the University of Warwick. His books include The Longman Companion to the French Revolution, The Cambridge Illustrated History of France, The Medical World of Early Modern France (with Laurence Brockliss) and Madame de Pompadour: Images of a Mistress.

For Mark and Robin

Salut et fraternit

Introduction

In many senses, the eighteenth century was Frances century. The long reign of Louis XIV (16431715) was widely viewed as Frances Grand Sicle (great century), yet by the kings death, the country had been reduced by European war and domestic circumstance to a wretched state: its economy was shattered, its society riven by religious and social discontent, its population reduced by demographic crisis, its cultural allure contested and found wanting, its political system in the doldrums. Yet the country was able to bounce back from misfortune and imprint its influence on every aspect of eighteenth-century European life. Demo-graphically, France was the largest of the great powers indeed between one European in five and one in eight was French. Socially and economically, the century witnessed one of Frances most buoyant and prosperous periods: though the benefits of economic growth were far from evenly distributed, the quality of life as measured by life-chances, income levels and material possessions marked a considerable improvement. Culturally, France was the storm-centre of the movement of intellectual and artistic renewal known as the Enlightenment: for most contemporaries, the lumire of this sicle des Lumieres shone from France. In terms of politics and international relations, France remained the power that other states had to take into account, to worry about, to keep if possible on their side. Although the monarchical system failed to adapt to the domestic strains and international pressures which the period produced, French courtly and administrative structures were very widely emulated down to 1789. Nor did the shift to a republic in 1792 halt the catalogue of achievement as was widely anticipated by European statesmen. Indeed, by 1799, France had vastly extended its frontiers and its influence over much of Europe.

To think of eighteenth-century France as the great nation did not rule out criticism. Indeed, writing a volume with this title invites dispassionate rather than eulogistic scrutiny of the criteria by which greatness is judged. By the end of the period, for example, as the Revolution of 1789 was taking a more militaristic and expansionist turn, the phrase la grande nation was used in quite opposing ways. For many it highlighted the world-historical achievements of republican France. Yet for others, both within France and without, it signified something altogether more sinister. The universalist rhetoric of human emancipation spouted by French administrators and generals contrasted strikingly with the narrowly materialistic, self-seeking and indeed pillaging activities which French armies were inflicting on other Europeans. The Rights of Man of 1789 seemed to be focused largely on the claims of the French to feather their own nest, and the phrase la grande nation often had a critical, grudging and ironic tinge.

There was, moreover, a deeper, historical irony in the use of the term by that time too. For by then the very criteria of international greatness were shifting in ways which would knock France off its perch and instal England in its place. This was not readily apparent in 1799: indeed, while France was brilliantly constructing a European empire, Englands political system was under strain, its financial strength seemed fragile, and its social fabric looked under pressure. With the benefit of hindsight, we can see that the British were by then establishing a lead in terms of economic growth, commercial strength, industrial force and political stability which would make them the worlds dominant power for much of the following century. And in 1815, France would be rolled back to its 1792 frontiers in a manner that smacked of national humiliation. But that is another story.

If historians have often failed to recognize the extent of the achievement of the French nation in the period from the death of Louis XIV until the advent of Napoleon, this is partly at least because the period was topped and tailed in 16891713, then in the decade leading up to Waterloo in 1815 by heavy military defeats at the hands of Britain and its allies. The lack of recognition owes much to the fact that much of the history written about this period focuses on the Revolutionary era of 178999. So prevalent has been the view that the 1789 Revolution was not of a piece with the rest of the century that Alfred Cobbans A History of Modern France, vol. 1 (171599), published as long ago as 1957, remains the only history of the full period. Many historians have chosen to write as though the years prior to 1789 are only interesting insofar as they illuminate and help explain 1789. Digging for Revolutionary origins, they have tended not to look up and see the sources of strength as well as the problems and tensions within French pre-revolutionary society. The present study proceeds on the assumption that although the causes of 1789 constitute an important historical question, there are other issues about eighteenth-century France which also deserve to be taken seriously and given due attention. Many of these (the continuing power of the state, for example, Frances cultural and intellectual hegemony, its economic force, the roots of national identity) were grounded in Frances acknowledged strengths over this period rather than those weaknesses which directly influenced the outbreak of the Revolution.

Although one of my aims has been to convey much that was of significance in the social, economic, intellectual and cultural history of the period from 1715 to 1799, I have highlighted political history, which provides an essential framework for understanding both the achievements and the problems about French society over the period as a whole. The work thus will reflect the remarkable revival of interest among historians in eighteenth-century politics since Cobbans time, yet do so in a way which places politics in relation to broader developments. A thread of political narrative provides the works organizing principle; but it is heavily interspersed with analytical and contextual chapters.

I have tried to write a history which is enjoyable and instructive on its own terms and which needs no explanation. Many readers will thus be well advised to skip the remainder of this introduction, and to proceed to the opening chapters. However, I thought that fellow scholars would find it helpful if I outlined my approach, and highlighted how what I am offering reflects but also hopes to inflect existing historiographical trends. This is the aim of these introductory remarks.