Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this ebook to you for your personal use only. You may not make this ebook publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this ebook you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Dedicated to Eugen Weber, 19252007, Professor Emeritus, UCLA

To rule in France one must either be born in grandeur or else

be capable of distinguishing oneself above all others.

NAPOL ON I TO HIS BROTHER JOSEPH

I believe in Fate. If my body has miraculously escaped danger,

if my soul has managed to overcome every obstacle, it is because

I have been called upon to achieve something of significance.

PRINCE LOUIS NAPOLON, 1845

Fine carriages bearing famous gilded imperial coats of arms and elegant phaetons drawn by sleek, well-groomed horses were not an uncommon sight between the Rue de Mont Blanc and here before the stately mansion at 8 Rue Laffitte (then Cerutti). By four oclock on the afternoon of Wednesday, April 20, 1808, traffic was brought to a standstill, however, and even the troops in dress uniform lining the street could do nothing about it, a queue forming as these equipages passed through the large double iron gates and into the spacious cobbled courtyard, where these very unusual guests in elegant court costume descended.

Even in terms of imperial court receptions, the new arrivals were impressive, brought here on this special occasion to witness the signing of the acte de naissance , the certificate attesting to the birth of Hollands queen Hortenses latest son earlier this day. What was not only peculiar but unique about todays ceremony was the fact that on the document now presented, the space where the names of the newly born boy should have been printed was left blank. Nevertheless, the reason was simple enough, for Emperor Napolon was not present, and no child of the imperial family could be named without his approval and blessing. If the emperor could be excused, the absence of King Louis, the childs father, could not, nor did his ambassador today provide a reason for his remaining in Holland. But of course the rift, the official separation of Louis and Hortense, was hardly a secret in court circles.

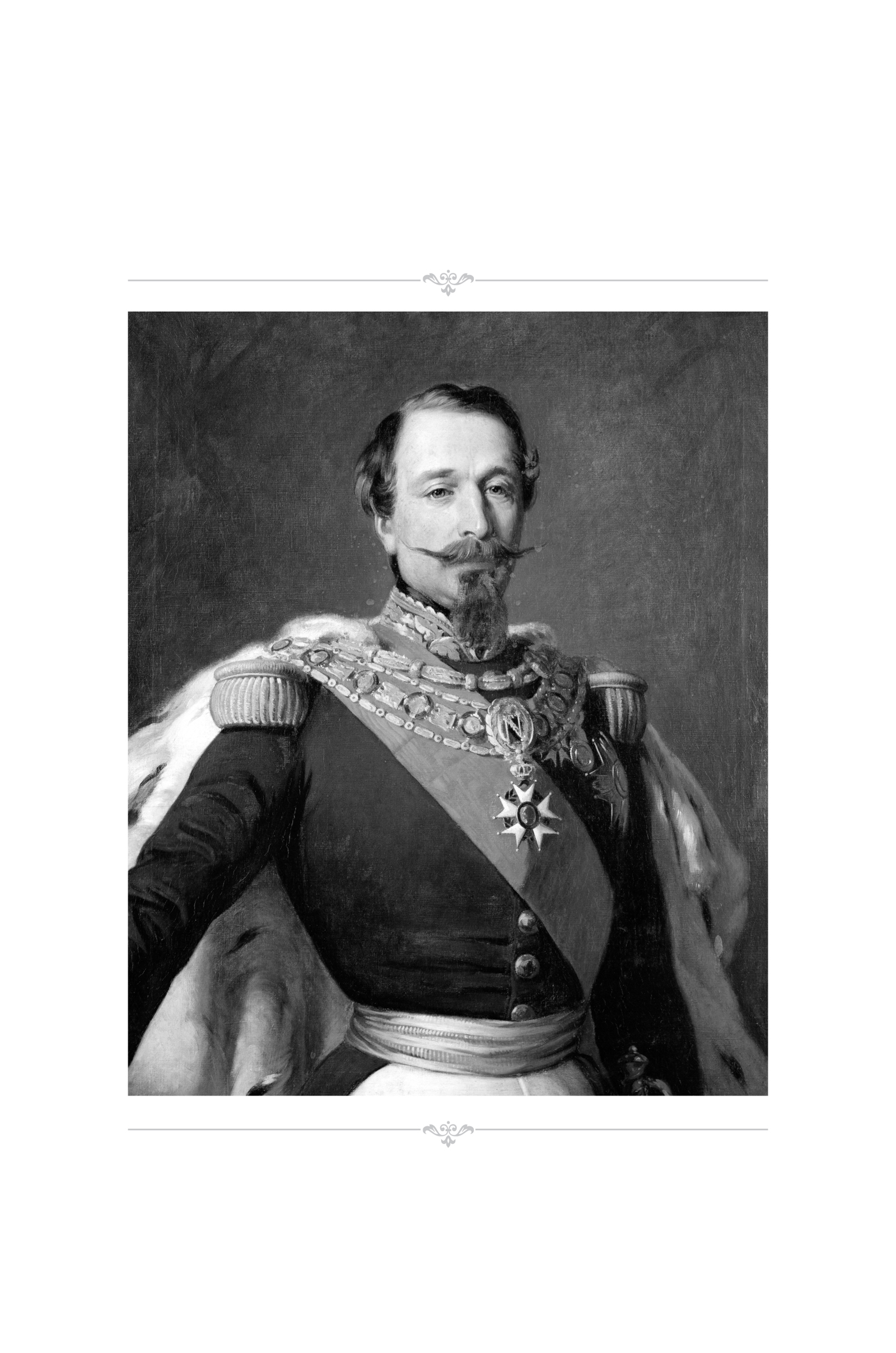

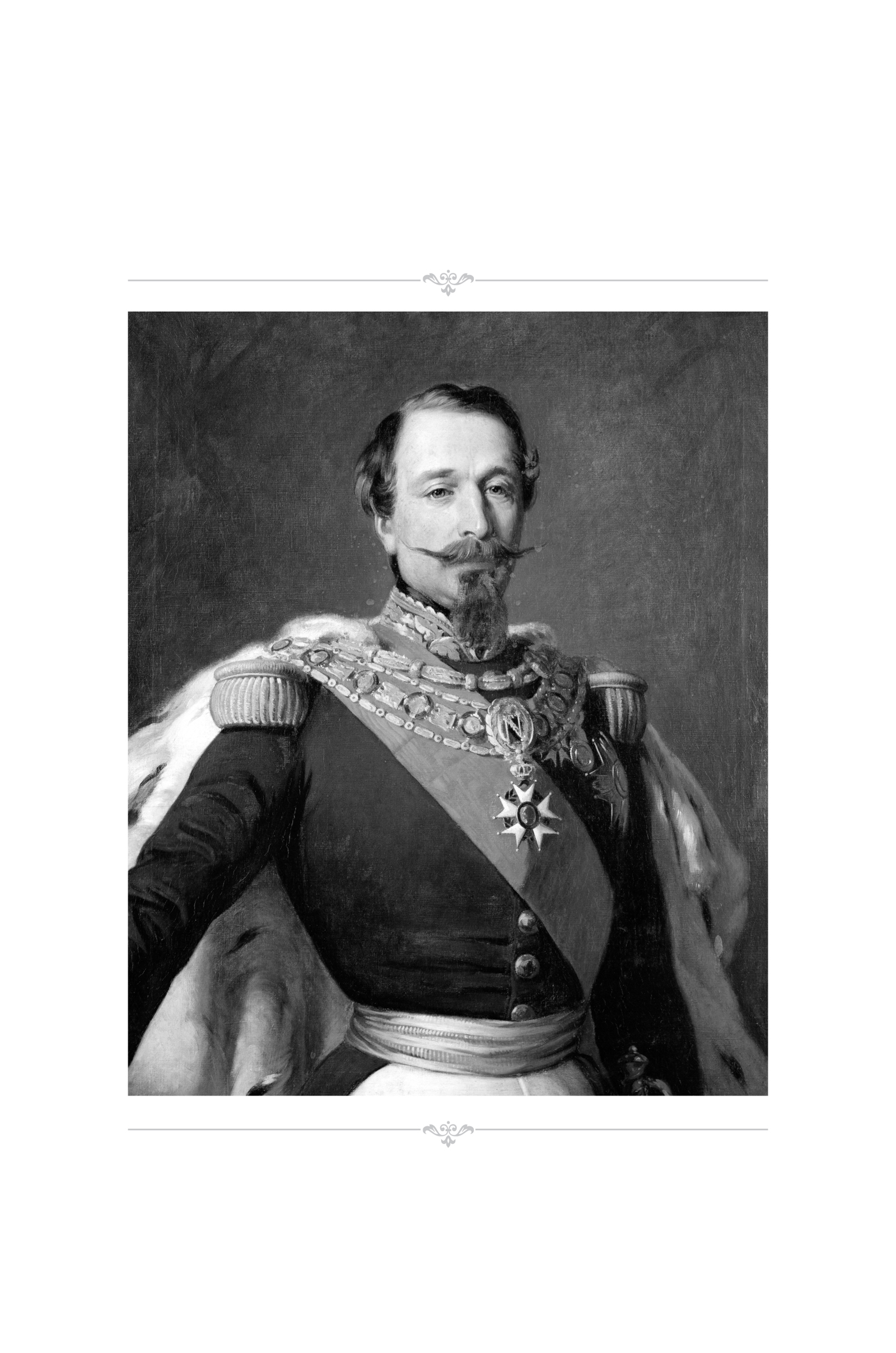

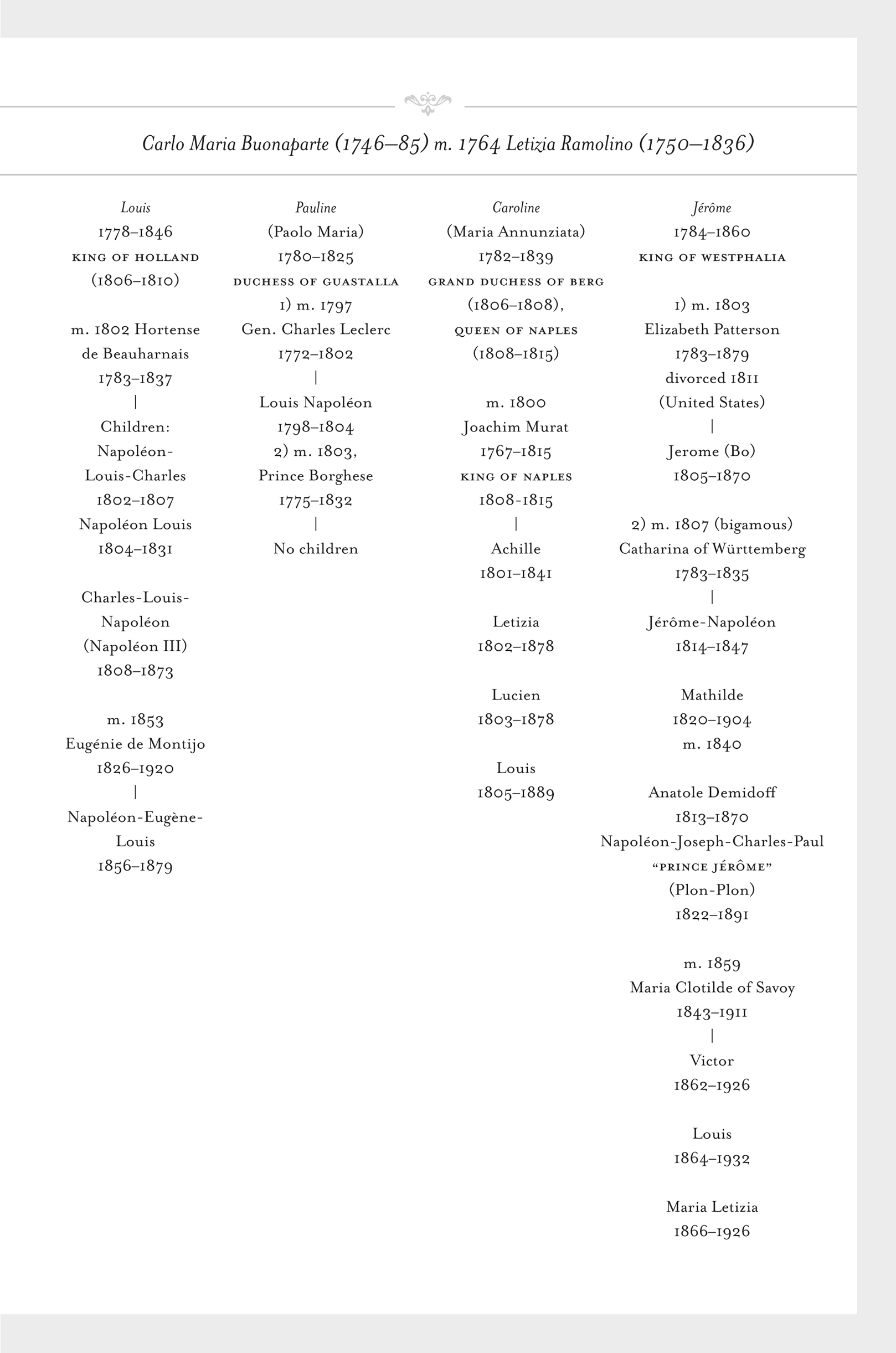

On the second of June, Napolon finally announced the babys name: Charles-Louis Napolon, better known as Prince Louis Napolon, the future ruler of France as Napolon III.

* * *

Since the fall of Napolons Empire in 1815, existence for ex-queen Hortense, now known officially as the Duchess de Saint-Leu, had been far more complicated and painful, indeed a veritable nightmare. For as charming and delightful as the five Allied rulers found the lovely daughter of Josphine, nevertheless she was an important political figure as the wife of Napolons brother Louis, whose two surviving sonsPrinces Napolon Louis Bonaparte and Louis Napolon Bonapartestood in line to the imperial succession. The new Bourbon king, Louis XVIII, banned Hortense, and all members of the Bonaparte clan, from French soil. Traveling to Aix-les-Bains (Savoy), she and her sons had fled to Switzerland and then across the German frontier to Constance in southern Bavaria, only to be ordered out of that country. In 1816, Hortenses cousin, Stphanie de Beauharnais, now the Grand Duchess of Baden, offered her and her sons a haven at Carlsberg, only for Hortense to find herself and her family obliged to move once more when a relentless Louis XVIII put great pressure on the Grand Duke of Baden as well. Uprooted again for at least the fifth time with young sons in tow, a by now desperate Hortense appealed to her brother, Eugne de Beauharnais, as the son-in-law of King Maximilian I of Bavaria, for help.

Overcoming the kings anxieties, Eugenes intervention proved successful, and by February 1817 Hortense was authorized by the five Allies to settle in the prosperous medieval city of Augsburg in western Bavaria.

In 1817 the Swiss Federated Governmentthrough the council of the northern Canton of Thurgaualso issued permission for Hortense to settle in Switzerland. After two years of perpetual peregrinations and anxiety, she could now purchase her own house, in fact two of them (including the nearby Swiss estate of Arenenberg). At the same time, after long, difficult negotiations, a settlement was reached with Louis Bonaparte. Their eldest son, Napolon Louis Bonaparte, would remain with his father in Italy, while his younger brother, Prince Louis Napolon, the future emperor, would be brought up by Hortense.

The past couple of years of continuous personal upheaval and uncertainty had taken a permanent toll on both Hortense and her son Louis Napol o n. Always at the back of her mind was the anxiety that soldiers would once again appear on her doorstep with signed orders from the British Foreign Office and the other four members of the Allied coalition to expel her and her young family from yet another country. That young Prince Louis Napol o n became as cautious and wary as his mother of people and of the proffered friendship of newcomers was hardly surprising. Who in the final analysis could they really trust and rely upon? That anxiety remained with the prince the rest of his life. And this applied within the family as well, where some of their most determined enemies were to be found, including the otherwise mild Joseph Bonaparte.

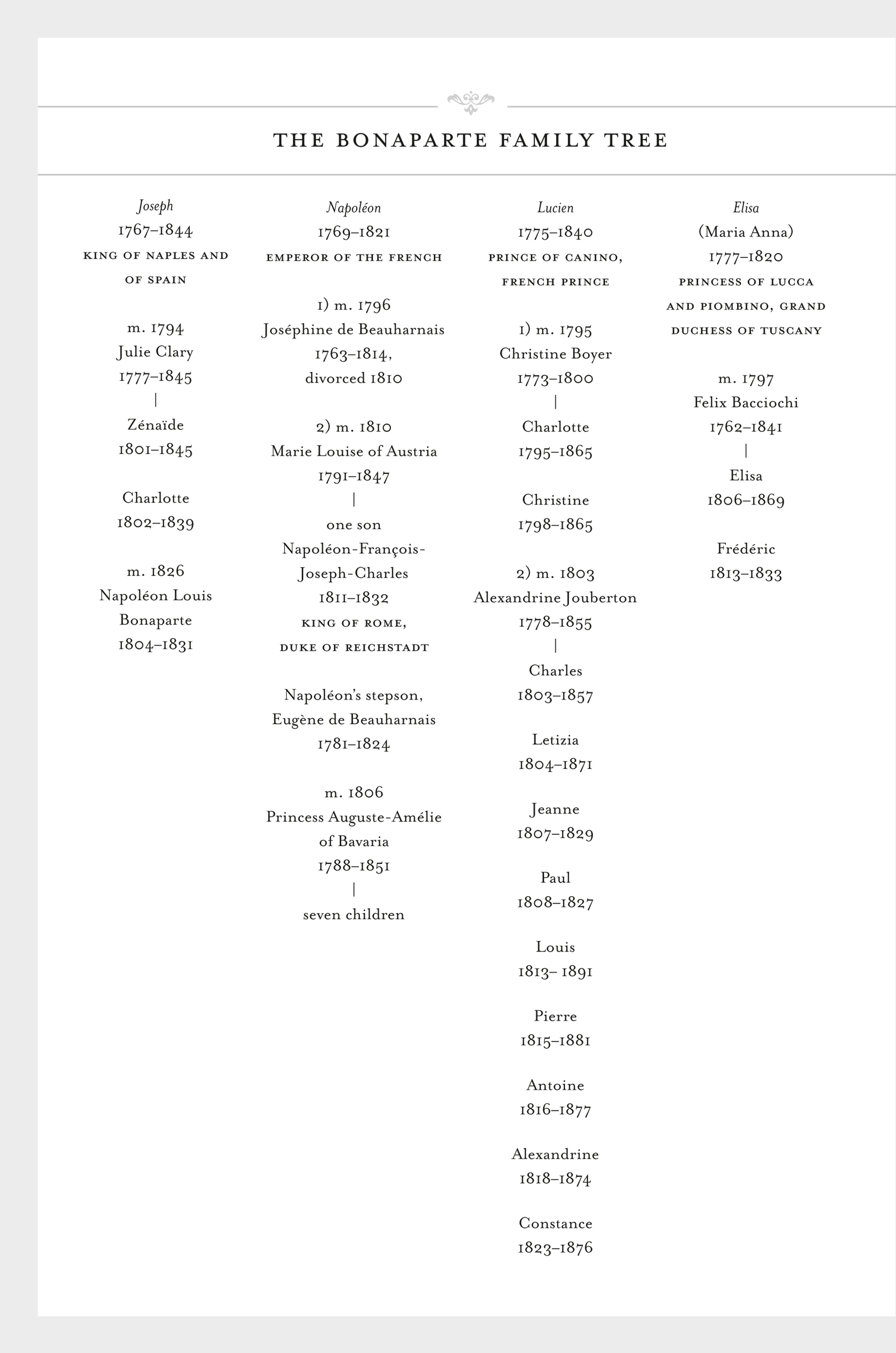

From the day of his marriage to Josphine, Napolon himself had had to contend with the open jealousy and hostility of his mother, Letizia, uncle Fesch, brothers Joseph, Louis, Lucien, and, sporadically, Jrme, not to mention his sisters. This enmity was only intensified following the imperial coronation in December 1804.

Now, more than a dozen years later, with Napolon thousands of miles away on St. Helena and the family dispersed to the four winds, this Corsican animosity toward Hortense and her sons remained undiminished. During the empire they had squabbled regarding the Napoleonic succession. That Napolon subsequently changed the order of that succession only intensified bitter familial rivalry that continued to this day, but was now aimed at Hortense and her two Bonaparte sons, who were high up on the list to succeed to the throne.

Napolon I had left his imprint on France. He had created a whole new post-revolutionary society and world in his own image and with it a whole new national mystique. Millions of Frenchmen had served in his armies and his state government. Millions of families, indeed every French man, woman, and child, had been affected by this dazzling if destructive genius who had altered their lives, while at the same time rampaged across the face of Europe like a rogue boar, suppressing kingdoms, monarchs, national frontiers, and political and legal systems, filling millions of graves in the process. Hundreds of cities, towns, and villages had been destroyed, hundreds of thousands of war refugees were forced to flee their ruined homes, and many tens of thousands of women and girls were raped, all because a madman wanted to satisfy his ego and conquer the world. There had been nothing like him and his bewildering legacy in two thousand years of European history.