PERMISSIONS

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to quote from the following sources:

Chandler, David G. The Campaigns of Napoleon, 1967, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1967.

Bruce, Evangeline. Napoleon & Josephine An ImprobableMarriage, Weindenfeld & Nicolson, 1996.

Thomazi, August Antoine. Napolon et ses marins, Berger Levrault, 1950.

Sutherland, Christine. Marie Walewska Napoleons Great Love, Weindenfeld & Nicolson, 1997.

Bertrand, Henri-Gratien. Napoleon at St. Helena the Journals ofGeneral Bertrand, Doubleday, 1952.

Graig, Gordon. The Politics of the Prussian Army 16401945, Oxford University Press, 19955.

Thiry, Jean, Napolon en Italie, Berger-Levrault, 1973.

Thiry, Jean, Les Annes de la Jeunesse de Napolon Bonaparte, Berger-Levrault, 1975.

A NOTE TO THE READER

Ever since his untimely death at the age of 51 on the forlorn island of St. Helena in 1821, Napoleon Bonaparte has too often been the victim of biographical and historical exuberance, of unhealthy literary passions that treat him either as demi-god (mainly French authors) or as devil incarnate (mainly British authors). The interpretive pendulum continues to swing, most recently toward devil incarnate in three lengthy books by American, British and French authors.

I object to either interpretation which, by distorting either his achievements or failures, gives the reader a lopsided view of one of the most fascinating persons of all time who dominated one of the most contradictory periods of the worlds history.

Napoleons relatively short life is a story of massive successes and disastrous failures, intense loves and violent hatreds, genius and stupidity, vision and cupidity, arrogance and ignorance, intrigue and treachery, short-term satisfactions and long-term frustrations of unfettered power once intended for the public good but in time diluted by overweening ambition and conceit.

Napoleon was not the father of chaos, as his detractors would have us believe. He was heir to chaos both at home and abroad. We tend to forget the appalling conditions of abject human servitude that fomented the French Revolution; the devastating period of terror invoked by Robespierre and his Jacobin followers; the inept and corrupt administration of the Directorate which followed the overthrow of the Jacobins. These miserable and chaotic years shaped the young Bonapartes thinking to bring forth his active participation in a coup detat followed by the creation of the Consulate and the Empire and a reasonably successful attempt by the new ruler to restore order in a torn nation while leading it to what he believed was its rightful role in the consolidation of Europe.

Neither was Napoleon the father of the wars that accompanied the process, as his detractors would also have us believe. Almost constant warfare was a legacy of the revolutionary chaos, a series of wars invoked by European and English rulers determined to topple the dangerous interloper and restore Bourbon feudalistic rule to France.

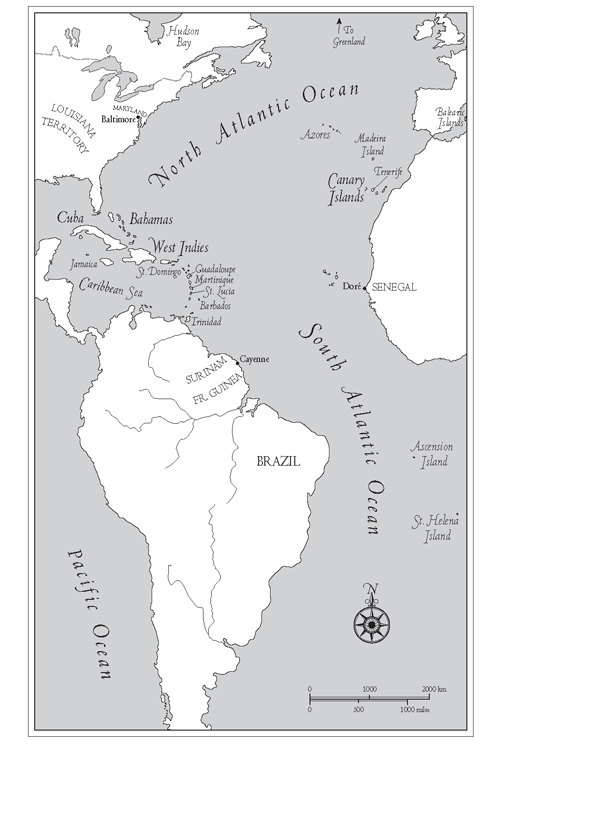

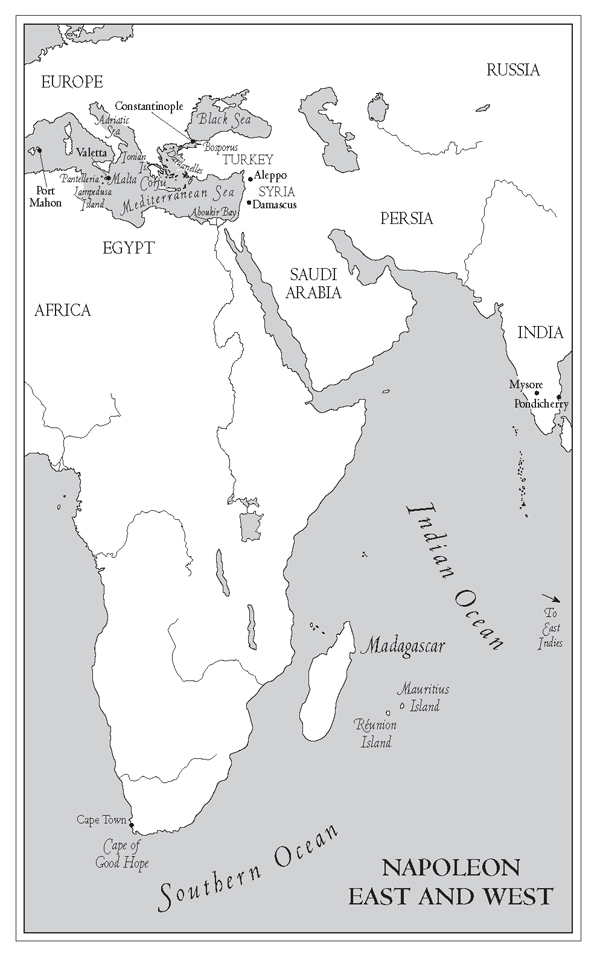

As European armies suffered repeated defeats owing to Napoleons military mastery, the desire of their governments for revenge continued to grow. It was fueled on the one hand by Napoleons determination to build a French empire in an attempt to unify a discordant Europe, on the other hand to force the English government to share its control of the seas: too often overlooked is the singular fact that in the first decade of the nineteenth century Britain controlled five-eighths of the worlds surface its oceans compared to Napoleons relatively slight and always tenuous European holdings.

The long Anglo-American alliance has tended to make many Americans forget the humiliations suffered by our colonial forefathers, the painful war that gave birth to our nation, the subsequent maritime insults to our fledgling navy and merchant ships, the war of 1812 and the burning of Washington. In Napoleons day the Royal Navy indisputably ruled the seas to provide its masters with a virtual monopoly of colonial trade that Napoleon was determined to break.

Since the English government had no intention of relinquishing its rule of the seas the results were inevitable. It was the English crown which dishonored its signing of the Treaty of Amiens to declare war on France in 1803; that bankrolled numerous Bourbon migr attempts on Napoleons life; that subsequently spent millions of pounds sterling in subsidizing a series of armed coalitions to make war on the French tyrant. And, because of Napoleons strategic errors, both military and political, it was the English crown that emerged the winner to continue enlarging its vast overseas empire throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.